(Edinburgh University Library Or. Ms 20)

The last two decades have seen a proliferation of publications variously questioning or outright denying the historical existence of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Although such views have gained practically no traction amongst academic specialists, they have attracted a considerable popular following, above all on the internet. The academic response to this popular challenge has been idiosyncratic at best, and there remains at present no systematic defence of the scholarly consensus that Muhammad existed. The present article fills this gap by surveying the arguments of the leading published proponents of “Muhammad mythicism” and evaluating whether they engage with all of the available evidence and provide satisfactory explanations therefor. The results of this survey are unambiguous: Muhammad mythicism is completely indefensible, and there can be no reasonable doubt that the founding prophet of Islam existed in history. Although this may be a foregone conclusion for academic specialists, there is value both in reevaluating and justifying conclusions that are simply taken for granted and in making these justifications accessible to non-specialists. In this respect, the present article is not merely an exercise in academic theory, but also public-facing scholarship that attempts to bridge the gap between the academic consensus and popular thinking regarding this major historical question.

1. The Rise of Muhammad Mythicism

In 1851, Ernest Renan famously and optimistically declared that Islam “was born in the full light of history”.[1] A century and a half later, however, John Lamoreaux gloomily acknowledged “the near total darkness that overshadows the first hundred years of Muslim intellectual history.”[2] Likewise, according to Keith Lewinstein:

Islam, unlike Christianity, is sometimes said to have been born “in the full light of history,” as Renan famously observed. But critics have begun to question just how bright that light actually is. While few if any question Muhammad’s actual existence, most critical scholars remain unconvinced that the historical Muhammad is to be found in this material and have lately raised fundamental questions about its origins and historicity.[3]

The reason for this radical shift in the perceived visibility of the earliest phase of Islamic history is readily discernible: from the middle of the 19th Century onwards, successive waves of critical scholarship have exposed an ever-increasing number of problems with the early Islamic historical sources, each more devastating than the last. Broadly speaking, and to varying degrees, these historical sources—chiefly comprising large collections of short reports about Muhammad and other aspects of early Islamic history—are late, biased, propagandistic, anachronistic, implausible, contradictory, aetiological, and didactic; they originated as anonymous transmissions, only acquiring formal transmission-histories at a secondary stage; they originated as oral reports that were transmitted paraphrastically and atomistically in chaotic and rapidly-changing societal conditions; they underwent extreme mutation, distortion, growth, and transformation in the course of this early transmission; they exhibit signs of artificial narrative construction and often seem to derive from popular storytellers; many of them are exegetical speculations (i.e., attempts to explain and contextualise the Quran) disguised as historical narratives; and, in many respects, they appear to be fundamentally disconnected from Muhammad’s original Arabian environment.[4]

In the face of such a source-critical onslaught, it is little wonder that a general skepticism towards these sources came to predominate in the field of early Islamic history, especially regarding the life and times of Muhammad. Thus, already in 1914, Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje lamented: “In our sceptical times there is very little that is above criticism, and one day or other we may expect to hear that Mohammed never existed.”[5] Hurgronje’s words were prescient: in 1990, John Burton declared that, “however far back in the Muslim tradition one now attempts to reach, one simply cannot recover a scrap of information of real use in constructing the human history of Muḥammad, beyond the bare fact that he once existed—although even that has now been questioned.”[6] Now, thirty years later, such Muhammad mythicism has found expression in a number of publications.[7]

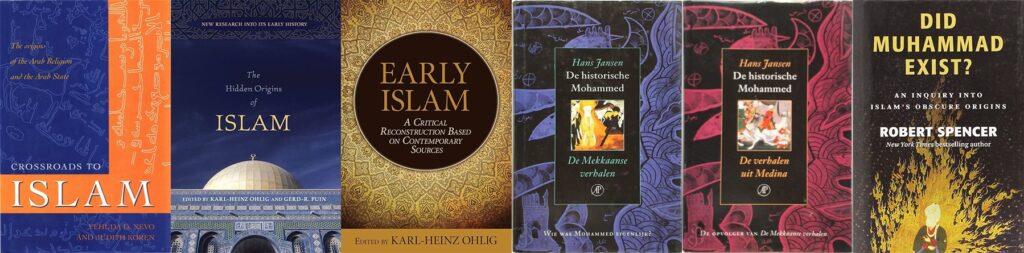

The first of these publications was Yehuda Nevo and Judith Koren’s 2003 monograph Crossroads to Islam, published after the former’s death in 1992. Right at the outset, the authors declared:

Muḥammad is not a historical figure, and his official biography is a product of the age in which it was written (the 2nd century A.H.). Muḥammad entered the official religion only ca. 71/690, and the very few passing references to him in earlier literary sources should be regarded as later interpolations by copiers who knew the Traditional Account.[8]

Next came various articles written by members of “the Institute for Early Islamic History and the Koran” (better known as Inârah), especially those by Karl-Heinz Ohlig and Volker Popp, which have been published in several collections. For example, Ohlig—in his forward to the 2010 collected volume The Hidden Origins of Islam—explicitly affirmed Nevo and Koren’s conclusion that “Muhammad is not a historical figure”.[9] Likewise, in a contribution to the 2013 collected volume Early Islam, Ohlig declared that “for a long time muḥammad was not a name, but a motto”, and that this motto “was first historicized and considered to be a name during the 8th century and supported by a biography in the 9th century.”[10]

Meanwhile, in a 2011 blog article, Hans Jansen—building upon his 2005-2007 two-volume series De historische Mohammed—expressed skepticism regarding Muhammad’s existence, writing:

Is Muhammad a historical figure? It may sound crazy but it is not as crazy as it sounds: a number of scholars consequently suspect that Muhammad is not a historical figure, but a literary character that was created by ancient Arab storytellers, perhaps early in the eighth century of our era. […] Nobody will as yet dare to uphold that we are forced to reject the historicity of the prophet of Islam, but doubt is perfectly justified…[11]

Jansen reiterated this skepticism in a forward he wrote for the first edition of Robert Spencer’s book Did Muhammad Exist?, stating:

…it is reasonable to have doubts about Muhammad’s historicity because there are no convincing archeological traces that confirm the traditional story of Muhammad and early Islam.[12]

Jansen was less confident in this conclusion than his predecessors, however, expressing various caveats concerning the evidence and couching his view as one of “doubt” rather than outright denial.

The most recent contribution in this nascent tradition of Muhammad mythicism is Spencer’s aforementioned Did Muhammad Exist?, first published in 2012 and reissued—in a revised and expanded form—in 2021. Spencer’s thesis—synthesising all of the preceding works—is most succinctly expressed in the following statement: “Muhammad was fashioned as a hero and prophet beginning toward the end of the seventh century and with increasing industry during the eighth and ninth centuries.”[13] Spencer wavers at times between this extreme position and the far more modest and defensible position that Muhammad’s image was considerably embellished in later Muslim narratives,[14] but it seems clear, especially in light of his subsequent interviews,[15] that Spencer really adheres to the first position. In other words, Spencer’s occasional expression of the second position is a kind of “motte-and-bailey” ruse: if challenged on the first (less defensible) position, Spencer can always retreat to the second (more defensible) position, even though he really believes the first.

For all that, Muhammad mythicism remains a fringe position within the academic study of early Islamic history, without practically any serious scholarly proponents: even Patricia Crone and Michael Cook, two of the most eminent skeptics and revisionists in the field in the last few years, always acknowledged that Muhammad was a historical figure.[16] Indeed, according to Chase Robinson:

No reasonable historian familiar with all of the evidence doubts that Muhammad existed, that many Arabs acknowledged him as a prophet in a line of monotheist prophets, that he was genuine in his belief in receiving revelations that would be recorded in the Qurʾan, or that Arab armies defeated the Byzantines and Sasanians in a series of battles that established Islamic rule across much of the Mediterranean and Middle East. With the exception of a hyper-sceptical fringe, all of that is beyond controversy.[17]

Despite this overwhelming academic consensus, Muhammad mythicism has garnered popular support on the internet,[18] to the point that any researcher of early Islamic history with an online presence will inevitably encounter its proponents. This fact alone may provide a warrant for the present article: in an era of academic outreach and public engagement, when scholars are increasing appearing on podcasts, running social media accounts, and writing books with general audiences in mind, there may be some benefit to clearly and systematically explaining, in a public forum, exactly why the overwhelming majority of scholars accept that Muhammad existed. Beyond this, there may be some benefit in such an exercise even for academics, and certainly for students: it is always helpful to remind ourselves how to justify conclusions that have long since been taken for granted, especially when recent developments and discoveries in the field may lend strength thereto. To this end, the present article surveys the arguments of the leading proponents of Muhammad mythicism and evaluates both the degree to which they engage with the relevant evidence for Muhammad’s existence and the validity and plausibility of their explanations for the evidence.

Of course, other academics have already responded to some “Muhammad mythicist” claims and arguments; but these responses are usually sporadic, dealing with one or another issue, or one or two specific authors, without providing an overarching or systematic response to the underlying thesis.[19] There is thus still a need for a robust defence of the academic consensus that Muhammad existed—a defence that the present article will offer.

2. The Arguments for Muhammad Mythicism

The starting point of Muhammad mythicism is the last century or so of critical scholarship described above, which has convincingly shown that the extant Islamic historical sources are substantially unreliable.[20] Alongside this, all of the writers under consideration reject the traditional narrative of the Quran’s canonisation in the early-to-mid 7th Century CE, advocating instead for a canonisation c. 700 CE or even later.[21] Having thus rendered all Islamic literary and documentary sources late and suspect, these writers then search for writings on Muhammad in the 7th Century CE and discover either that no such writings exist,[22] or that the putative non-Muslim writings from that era are later interpolations,[23] or else that these non-Muslim writings are somehow not referring to Muhammad.[24] Additionally, these writers discover that, whilst there are some early Muslim coins and inscriptions that do seem to refer to Muhammad, these only appear towards the end of the 7th Century CE and also do not actually refer to a man named Muhammad.[25]

There is thus no contemporaneous or even early references to an Arabian religious leader named Muhammad who lived and operated at the beginning of the 7th Century CE: the Islamic historical sources are all from more than a century and a half later; the Quran is from nearly a century later at least; the early non-Muslim writings were interpolated (a century or more) later and/or do not actually refer to Muhammad; and the early Muslim inscriptions are from at least half a century later and do not actually refer to Muhammad. From all of this, the proponents of Muhammad mythicism derive an argument from silence: if Muhammad existed (e.g., as the founder the religious community that would evolve into the Arab Empire), then we would expect to find contemporaneous or at least early references to him (in Muslim inscriptions, non-Muslim writings, etc.); there are no contemporaneous or early references to him; therefore, we have strong reason to doubt his historical existence.[26]

Most Muhammad mythicists go a step further, however, arguing not just that there are no contemporaneous or early references to Muhammad, but also, that the references that we do find actually refer to Jesus. In other words, the early Muslim inscriptions that mention “muhammad” are actually referring to Jesus via a title or epithet (“praiseworthy one” or even “chosen one”), not a proper name (let alone the proper name of a recent Arabian man). It was only at a secondary stage, during the 8th Century CE, that this title or epithet was attached to an imagined founder of the Arab Empire and its emerging Islamic religion.[27]

Meanwhile, Jansen offers his own additional argument: even basic facts about Muhammad’s life appear to be symbolic narrative or literary constructions, rather than genuine biographical information. For example:

Even the names of some of the principle characters are suspect. Can it be coincidence that the names of Muhammad’s two most prominent wives, Khadiga and Aisha, have meanings that are each other’s opposite? Arabic khadiiga means ‘stillborn’, hence ‘dead’, whereas Arabic 3aa2isha means ‘living’, ‘alive’. Similar suspicions concerning the names of lesser figures abound.[28]

Likewise, even the basic chronology of Muhammad’s life appears to have been created according to numerological or aesthetic sensibilities, rather than any kind of genuine historical memory. For example:

We have to live with even more coincidences. The symmetry of the chronology of the official version of the early history of Islam is absolutely amazing. Muhammad spent ten years as a preacher in Mecca, followed by ten years as a statesman in Medina. Ten years before Troy, ten years travelling back to Ithaca. It is not impossible, but probable it is not.[29]

It would thus seem, according to Jansen, that Muhammad is a fundamentally literary or mythical character, whose basic biography has been constructed, rather than simply being embellished in the details.

In short, the leading proponents of Muhammad mythicism primarily appeal (1) to the unexpected absence of any contemporaneous or early references to an Arabian religious leader named Muhammad; (2) to the proto-Islamic use of “muhammad” as a title or epithet for Jesus, rather than the name of an Arabian man; and (3) to the fundamentally mythic character of even the basic elements of Muhammad’s putative biography. On these baseis, they conclude not merely that there is no positive indication that Muhammad existed, but further, that Muhammad plausibly or even likely did not exist.

3. The Arguments against Muhammad Mythicism, Part 1: The Worst-Case Scenario

Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that the situation with the sources is, at least broadly, as dire as the proponents of Muhammad mythicism claim: that the extant Islamic historical sources all date from the 9th Century CE onward and are extremely unreliable; that the Quran was only collected and canonised c. 700 CE; that inscriptional and numismatic references to a certain “muhammad” only appear towards the end of the 7th Century CE; and that all of the early non-Muslim writings that appear to refer to Muhammad are under suspicion of being later interpolations. In such a situation, would it be reasonable to doubt Muhammad’s existence?

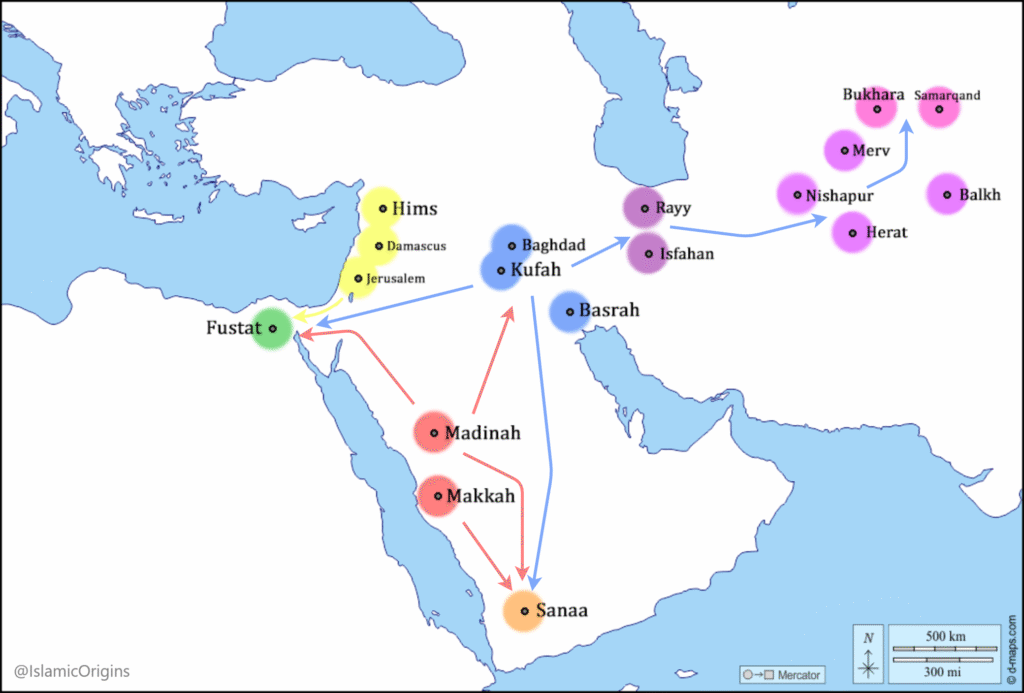

To answer this question, it is necessary to clarify the character and provenance of the extant Islamic historical sources. Most of these sources are collections of short reports that fall within a certain genre, including biographical collections (on the life and times of Muhammad); legal collections (on the prescriptions, proscriptions, and practices of Muhammad and other early Muslim authorities); exegetical collections (on the meaning and context of the Quran); antiquarian collections (on pre-Islamic Arabia); conquest-related collections (on early Muslim military history); and general historical collections (on the political history of the caliphate). Alongside such collections, there are also geographies, epistles, heresiographies, biographical dictionaries, and other works that intersect in various way with early Islamic history. These sources were written or compiled by authors hailing from all across the early Arab Empire, including Arabia, Iraq, and Iran; and many of these authors travelled widely and collected material from multiple regions as well. Finally, both the authors and the material that they collected hailed from diverse and competing ideological backgrounds, including rival sects (Sunni, Shiʿi, Ibadi, etc.) and rival politico-tribal factions (the Umayyad family and its allies, the Hashimid family and its allies, etc.).[30]

The extant Islamic historical sources thus constitute a vast corpus of material from diverse backgrounds, from multiple locations across the early Arab Empire and from multiple sectarian communities, all of which affirms Muhammad’s historicity. In other words, all of these sources agree that Muhammad was a man who lived in Western Arabia at the beginning of the 7th Century CE; that he was a member of the Quraysh tribe; that he married a woman named Khadijah and another named ʿAʾishah, amongst others; that he led a religious community in the town of Medina and fought against rival groups in Western Arabia; and that his community went on to establish the Arab Empire after his death. Already, the simplest explanation for this unanimous agreement—for the shared conviction of countless individuals living in Arabia, Syria, Iraq, and beyond, from Sunni, Shiʿi, and other backgrounds, in the 9th and 10th Centuries CE, that the founder of their religion was a man who lived in Western Arabia in the early 7th Century CE—is that Muhammad was indeed a man who lived in Western Arabia in the early 7th Century CE. In other words, the simplest explanation for this unanimous agreement is a broadly accurate collective memory: each early Muslim community independently inherited the same basic memory of the founder of their religion. Naturally, each community remembered things differently, and reports that arose in one community certainly spread to others; but overall, they shared, through common inheritance, the same basic memory of a historical Muhammad. Other explanations for this universal consensus are of course possible, but would require a more complicated process, involving not just the full-scale creation of Muhammad’s basic biography, but also, its spread across the Arab Empire and its universal acceptance amongst all of the Muslims therein. Thus, all else being equal, the simplest hypothesis—that Muhammad existed and was broadly remembered by his diverse and dispersed followers more than a century and a half later—is to be preferred for the data in question.

Muhammad’s historicity is all the more likely given the diverse sectarian provenance of the Islamic sources: no matter where we look, whether the sources be Sunni, Shiʿi, Ibadi, or something else, the same basic picture of Muhammad emerges.[31] For the Muhammad mythicist hypothesis to be true, it would have to be the case either that multiple rival sectarian communities independently or synchronously created the same false biography of Muhammad, which seems vanishingly unlikely; or else that one of these sectarian communities created a false biography and somehow transmitted it—successfully—to every other sectarian community, which also seems unlikely. Are we really supposed to imagine, for example, that a member of one early sectarian or political community created a historical character named Muhammad, identified him as the founder of their religion, and then convinced a rival community that they too shared this founder? Are we then to imagine that this process repeated itself over and over, until every putatively Islamic sectarian and political faction in the 8th or 9th Century CE came to accept the same basic origins narrative? Once again, it is not impossible; but once again, it seems highly implausible.[32]

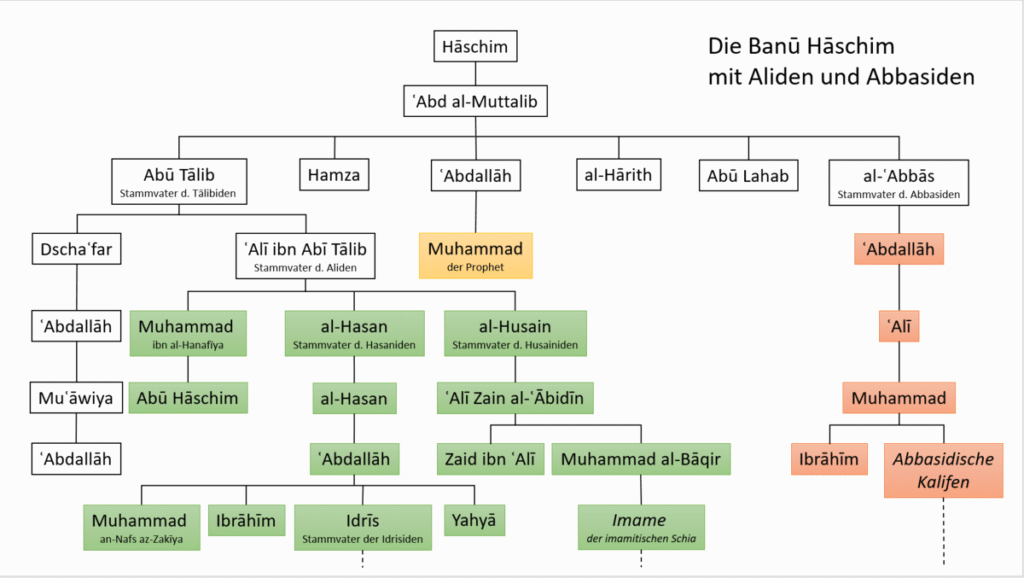

Muhammad’s historicity is even more likely given the highly inconvenient nature of his basic biography for some of the early factions who nonetheless accepted it. For example, even members and supporters of the Umayyad family (within the broader Quraysh tribe) accepted that Muhammad was a member of the rival Hashimid family, rather than a member of their own immediate family.[33] It is extremely difficult to imagine that, in the 8th Century CE, the Umayyads and their supporters were somehow all convinced of a false pro-Hashimid claim that Muhammad was in fact a Hashimid; let alone that the Umayyads themselves created such a genealogy.[34] Once again, all else being equal, the overwhelmingly likely explanation for the consensus of the extant Islamic historical sources that Muhammad existed as a man in Western Arabia at the beginning of the 7th Century CE, etc., is that later Muslims collectively inherited a broadly accurate memory of the founder of what became their religion.

Of course, all else is not equal, according to the Muhammad mythicists: for example, according to Jansen, even the basic elements of Muhammad’s biography are artificially constructed, including his wives. There are two problems with Jansen’s chosen example, however. Firstly, whilst it is certainly true that the name ʿAʾishah literally means “something that is alive or living” and that Khadijah literally means “stillborn”, it is simply false that these two “are each other’s opposite”: the antonym of “alive” is “dead”, and “stillborn” is not a synonym for “dead”. If indeed Muhammad’s two wives had been constructed in a symbolic and symmetrical fashion, we would instead expect ʿAʾishah (“something that is alive or living”) to be paired with Maʾitah (“something that is dead or dying”), its actual opposite. More importantly, Jansen omits an important fact in order to make the superficial correspondence between these two names seem meaningful: Muhammad reportedly married more than a dozen women. It is thus not at all remarkable that at least two of the names reported for his numerous wives would happen to correspond to vaguely opposing concepts. Certainly, there is no reason to think that all of Muhammad’s marriages embody some kind of mythic construction.

Jansen’s point about the artificiality of the chronology of Muhammad’s life is even less convincing. To be sure, the extant chronology of Muhammad’s life is exactly as Jansen says: substantially artificially constructed according to numerology, aesthetics, symbology, etc.[35] However, the idea that this calls into question the historicity of Muhammad’s biography in general is completely fallacious: it does not follow, merely from the fact that early Muslims invented a somewhat false chronology of Muhammad’s life, that they invented his life more broadly. On the contrary, this is exactly what we would expect to see, even on the view that Muhammad was historical: the earliest Muslims lived in a stateless society that was largely devoid of bureaucracy, intensive record-keeping, or even systematic written scholarship (i.e., precisely the kind of society that does not usually preserve chronological data), so it is only to be expected that the extant chronology of Muhammad’s life would be some kind of secondary, artificial creation by later Muslims.[36]

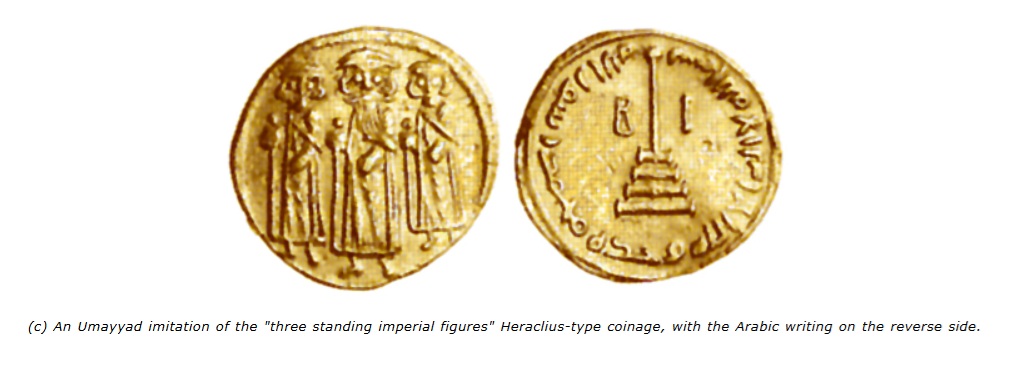

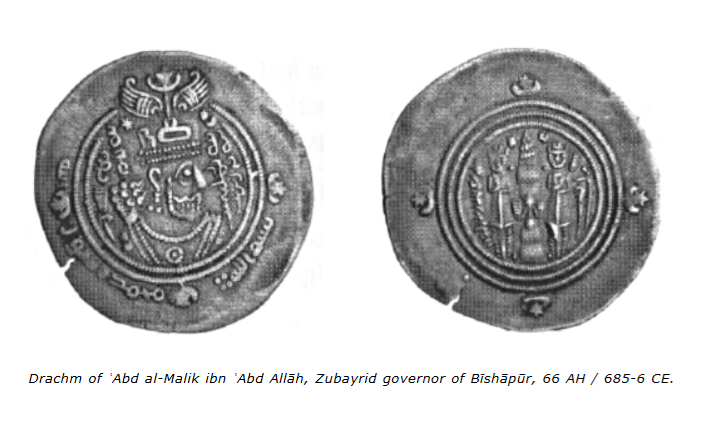

Of course, all of this still leaves the problem of the absence of references to Muhammad until the last quarter of the 7th Century CE: the earliest reference to him appears on coins issued by the short-lived Zubayrid regime c. 685-687 CE (amidst the second Islamic civil war), half a century after his death. Thereafter, references to Muhammad proliferate in the official media of the victorious Marwanid Dynasty, including on coins and the famous Dome of the Rock (completed c. 691 CE). All of these inscriptions—Zubayrid and Marwanid alike—proclaim the same now-standard Islamic formula: “Muhammad is the Messenger of God.”[37] Can this half-century gap between Muhammad’s death and these inscriptions be explained in a satisfactory way by proponents of Muhammad’s historicity?

The answer, of course, is ‘yes’: this initial inscriptional absence is only even putatively a problem if we assume that the earliest Muslims were like later Muslims in terms of their conception of Muhammad. In other words, the argument from silence relied upon by Muhammad mythicists assumes that 7th-Century Muslims, like their 8th- and especially 9th-Century counterparts, were already obsessed with Muhammad as a source for norms and an object of devotion. This is a highly unsafe assumption, however: on the contrary, it seems clear that the authority and status of Muhammad was elevated over time as Muslim conceptions evolved, which is to say, Muhammad was far less important to early Muslims than he was to later Muslims.[38] The initial absence or paucity of Muslim inscriptions referring to Muhammad thus poses no problem at all for the hypothesis of his historicity, since it fits comfortably with our established background knowledge on the evolution of early Muslim thinking: if the earliest Muslims had a much more mundane view of Muhammad and were more focused on correct belief in God, for example, than we might not expect them to refer to Muhammad—as opposed to God—in the first place.[39]

To be sure, there are other possible explanations for the initial absence or paucity of references to Muhammad as well, including the hypothesis that he simply did not exist. However, here we encounter a basic methodological problem with Muhammad mythicism: when faced with (1) a viable explanation of the data that coheres with other evidence and (2) another explanation that conflicts therewith, the mythicists invariably opt for the latter. This is simply to adopt an inferior explanation: if a perfectly viable explanation is available (e.g., Muhammad was initially less important) that also matches all of the other available evidence more broadly (e.g., the overwhelming trans-regional and trans-sectarian consensus of the extant Islamic historical sources), then—all else being equal—that explanation is clearly to be preferred. Even putting that aside, the mythicist explanation of the initial absence is simply one amongst many (i.e., tentative; a mere possible explanation) and thus cannot dislodge the powerful evidence of the consensus of the Islamic historical sources, which strongly supports historicity over mythicism.

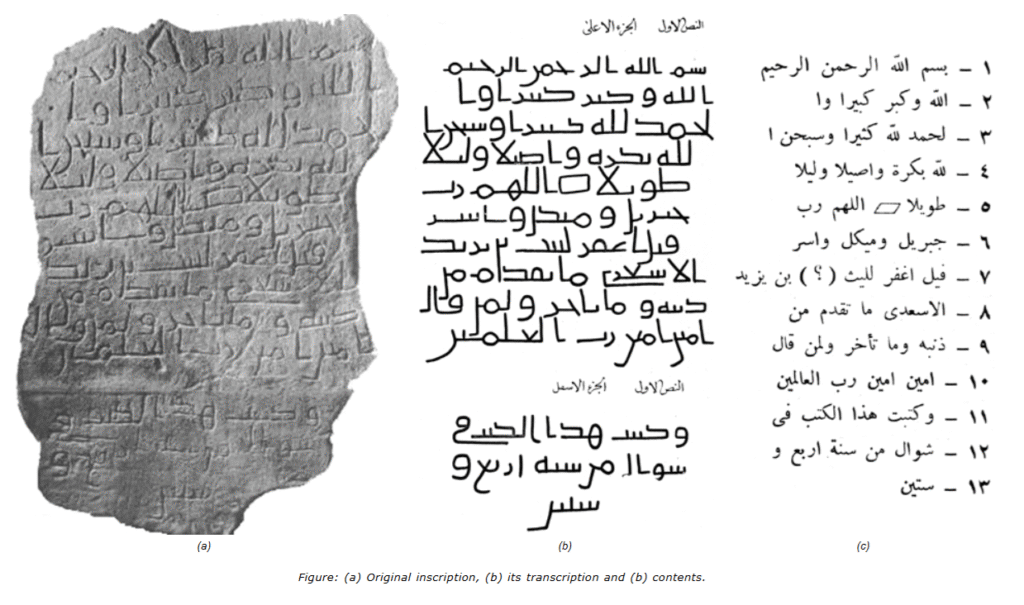

Of course, many Muhammad mythicists claim that there is a fundamental problem with the earliest inscriptions referring to Muhammad, beyond simply their lateness: rather than referring to a recent Arabian man named Muhammad, they are actually referring to Jesus via the title or epithet “praiseworthy one” or “chosen one”. To begin with, such mythicists reinterpret the literal meaning of the word muhammad from “praiseworthy one” to “chosen one”,[40] for obvious reasons: if God’s chosen prophet just so happened to be named “chosen one”, that would indeed be suspicious. However, there are no good grounds for such a reinterpretation: for example, the “praise” meaning of the Arabic hamd root (from which the name “Muhammad” is formed) is already evident in an Arabic graffito from 683-684 CE, in which the phrase al-hamd li-llah (“praise be to God”) appears amidst other praising formulas:

In the name of God, al-Rahman, the Merciful. God is very great (allah akbar kabiran)! Much praise be to God (al-hamd li-llah kathiran)! Praise be to God (subhan allah), morning, evening, and all night long! O God, Lord of Gabriel, Michael, and Israfil: forgive […] b. Yazid al-Asʿadi for his earlier sins and those that came later, and [forgive] whoever says, “Amen! Amen! Lord of the World-Dwellers!” This text was written during [the month of] Shawwal, in the year 64 [i.e., 683-684 CE].[41]

In other words, we have unambiguous evidence that hamd already meant “praise” at exactly the time when “Muhammad” inscriptions first appear, which strongly confirms the later consensus of the Arabic sources that hamd means “praise” and thus that muhammad—a passive participle derived from hamd—means “praiseworthy one”. It is also difficult to imagine, if muhammad originally meant “chosen one”, why such an auspicious meaning for either Christ’s title or the Prophet’s name would be downgraded over time to merely “praiseworthy one”: once again, it is far simpler to accept the overwhelming consensus of the later Arabic sources that muhammad always meant “praiseworthy one”.[42]

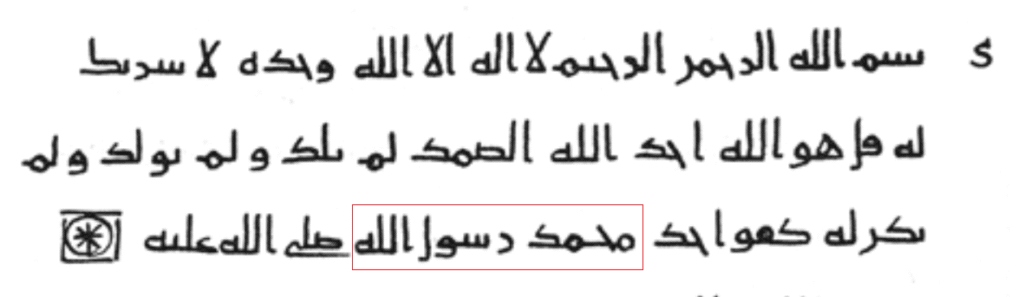

Many Muhammad mythicists also claim that muhammad in these inscriptions is an epithet or title for Jesus rather than the proper name of a recent Arabian man, or in other words: muhammad rasul allah should be read as “praiseworthy is the Messenger of God” (i.e., Jesus) rather than “Muhammad is the Messenger of God”.[43] This is a fairly straightforward misreading of the text: titles and epithets in Arabic are typically definite, so if indeed muhammad was a title or epithet, it ought to be accompanied by a definite article (al-muhammad), which it is not. However, given that muhammad rasul allah looks like a standard Arabic nominal sentence (“X is Y”), and given also that muhammad is in the first position in the sentence and thus likely the subject (the “X” in “X is Y”), and given further that subjects in nominal sentences are almost always definite, it follows that muhammad is still very likely definite. This creates a serious problem for the mythicist reading of this word, since there are only three ways that a noun can be definite in Arabic: (1) with a definite article; (2) as part of a possessive construct known as an Idafah; and (3) as a proper name. Given that muhammad lacks a definite article, and given also that the sentence in question turns into gibberish if it is interpretated as an Idafah (“the praiseworthy one of the Messenger of God”), there is only one viable explanation: muhammad is a proper name. In other words, the traditional reading of the formula muhammad rasul allah is beyond reasonable doubt: “Muhammad is the Messenger of God”. And, if Muhammad is a proper name, we would naturally expect “Muhammad” (whoever he is) to be someone different from “Jesus”, since people almost always have only one proper name. Thus, when we find both “Muhammad” and “Jesus” referred to on the Dome of the Rock, the obvious implication is that “Muhammad” is someone other than Jesus. In short, the mythicist interpretation of muhammad in early Muslim inscriptions makes little sense: this is clearly the proper name of a man who was regarded to be a Messenger of God, which perfectly matches the unanimous testimony of the later Islamic historical sources that their religion and community—of which the makers of these inscriptions were a part—was ultimately founded by a religious leader named Muhammad. Once again, the inscriptional evidence fits comfortably with a historicist view, not a mythicist view.

To all of this can be added two further considerations. Firstly, “Muhammad” is already attested as a proper name in a coin from 699-700 CE, which mentions a famous rebel named ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Muhammad, or in other words, ʿAbd al-Rahman, the son of Muhammad. This implies that Muhammad was already being used as a proper name in the middle of the 7th Century CE (in the generation preceding ʿAbd al-Rahman), well before the Zubayrid and Marwanid inscriptions under consideration.[44] Secondly, the word muhammad is left untranslated in both Persian and Greek texts from the mid-to-late 7th Century CE, which immediately suggests that it is a proper name: if it were simply a title, epithet, or description, then it ought to have been translated into the corresponding Persian and Greek titles, epithets, or descriptors, as in other cases.[45] All of this strongly supports the traditional interpretation of the relevant inscriptions: the “Messenger of God” is clearly a person named Muhammad.

This leaves only the silence of the early non-Muslim sources regarding Muhammad: the only ones that seem to mention him are all later interpolations, according to the Muhammad mythicists. If we accept this for the sake of argument, where does this leave us? It certainly would be curious that none of the various surviving non-Muslim sources mentioned the political founder and spiritual guide of the movement now conquering their authors, but this is nowhere near enough to dislodge the power of the pan-Islamic consensus discussed previously. Which is more likely: that the Arabic-speaking conquerors did not effectively communicate their origins to their new subjects, or that one proto-Islamic faction managed to convince every other competing proto-Islamic faction in the Arab Empire of the 8th Century CE that they all shared a recent founding figure that none of the rest had ever heard of before, etc.? Clearly, the former is far more likely than the other, or in other words: the alleged silence of the early non-Muslim sources is relatively weaker evidence that Muhammad did not exist and cannot overturn the far stronger evidence that he did exist.

4. The Arguments against Muhammad Mythicism, Part 2: A More Optimistic Scenario

All of the preceding argumentation conceded, for the sake of argument, that the Islamic historical sources only date from the 9th Century CE onward; that the Quran was only collected and canonised c. 700 CE; and that all of the relevant non-Muslim sources are later interpolations. In other words, even in the worst-case scenario, the hypothesis that Muhammad did not exist completely fails to account for the evidence in a convincing way, in contrast to the hypothesis that he did exist. However, these concessions were hypothetical: in actual fact, the situation with the sources is nowhere near as dire as the Muhammad mythicists claim.

To begin with, scholars are frequently able to reconstruct earlier versions of Islamic reports and trace them back to figures operating in the 8th Century CE, using a method known as “isnad-cum-matn analysis”.[46] In fact, using this method, a veritable corpus of reports about Muhammad’s life has been reconstructed back to a figure named ʿUrwah b. al-Zubayr (d. 711-714 CE), operating less than a century after Muhammad’s death.[47] ʿUrwah is certainly not an eyewitness, but he did claim to have received some information about Muhammad from eyewitnesses: his traditions alone show that, already at the end of the 7th Century CE, it was widely taken for granted that Muhammad was a man who had lived in Western Arabia two generations earlier, raised a family, founded a religious community, etc.

Moreover, the extant Islamic historical sources preserve a transcription of a treaty that was drawn up by Muhammad himself when he established his religious community in the town of Medina (originally known as “Yathrib”). The treaty opens:

This is a document from Muhammad the prophet (al-nabi), between the Believers and the Muslims of Quraysh and Yathrib and those who follow them and attach themselves to them and struggle alongside them. Verily they are one community (umma) to the exclusion of [other] people.[48]

The content of this treaty conflicts with later Muslim sensibilities in a number of ways, which makes it extremely unlikely that it was created by later Muslims; thus, it is likely authentic, as practically all scholars agree.[49] In other words, we have access to an archaic document that not only mentions Muhammad, his community, and the town they lived in, but which was drawn up by none other than Muhammad himself.

Furthermore, numerous, independent points of evidence all establish, unambiguously, that the Quran was canonised in the middle of the 7th Century CE, under the early Muslim caliph ʿUthman b. ʿAffan (r. 644-656 CE): every single Islamic report on this issue agrees that ʿUthman canonized the Quran; even early Muslim sects and factions who despised ʿUthman accepted this fact; the reports to this effect can be traced back as early as the beginning of the 8th Century CE; the Quran contains no references to the politics, conflicts, institutions, etc., of the late 7th Century CE; and so on, so forth.[50] And, as it happens, the Quran directly refers to Muhammad four times:

[Q. 3:144] Muhammad is nought but a messenger. Other messengers have gone before him. If he were to die or be killed, would you turn on your heels [i.e., away from his message]?

[Q. 33:40] Muhammad is not the father of any of your men. However, [he is] the Messenger of God and the Seal of the Prophets.

[Q. 47:2] Those who have faith and enact righteous deeds and believe in that which was revealed to Muhammad—which is the truth from their Lord—will be absolved of their sins by Him and improved in their condition by Him.

[Q. 48:29] Muhammad is the Messenger of God. Those who are with him are harsh towards the disbelievers [but] compassionate amongst themselves.

Once again, most of these statements would be gibberish if “muhammad” was simply a description rather than a proper name. This means that, already in the middle of the 7th Century CE, we have a source that explicitly mentions an Arabian religious leader named Muhammad.

Additionally, the idea that all of the relevant non-Muslim writings are later interpolations is completely unjustified: the leading experts thereon all affirm that the writings are genuinely early, variously dating back to the middle and even the early 7th Century CE.[51] For example, a Mesopotamian priest named Thomas wrote the following c. 640 CE:

In the year 945 [i.e., c. 634 CE], indiction 7, on 4 February, on Friday, at the ninth hour, there was a battle between the Romans and the Nomads of Muhammad [ṭayyāyē d-mḥmṭ] in Palestine, twelve miles east of Gaza.[52]

Two decades later, around 660 CE, another Syriac author—known as the Chronicler of Khuzistan—similarly wrote the following:

And Yazdgerd, who was from the royal lineage, was crowned king in the city of Eṣṭaḵr, and under him the Persian Empire came to an end. And he went forth and came to Seleucia-Ctesiphon [Māḥōzē] and appointed one named Rustam as the leader of the army. Then God raised up against them the sons of Ishmael like sand on the seashore. And their leader was Muhammad, and neither city walls nor gates, neither armor nor shields stood before them. And they took control of the entire land of the Persians. Yazdgerd sent countless troops against them, but the Nomads [ṭayyāyē] destroyed them all and even killed Rustam.[53]

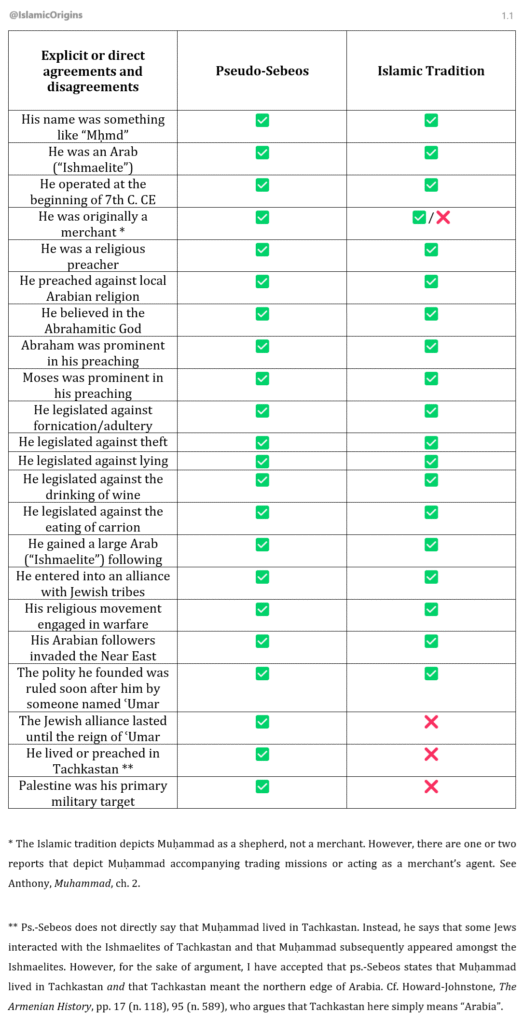

For a final example, an unnamed Armenian chronicler writing in the early 660s CE—often known as pseudo-Sebeos—recorded an actual biographical summary of Muhammad, on the authority of an earlier source:

At that time a man appeared from among these same sons of Ishmael, whose name was Muhammad, a merchant, who appeared to them as if by God’s command as a preacher, as the way of truth. He taught them to recognize the God of Abraham, because he was especially learned and well informed in the history of Moses. Now because the command was from on high, through a single command they all came together in unity of religion, and abandoning vain cults, they returned to the living God who had appeared to their father Abraham. Then Muhammad established laws for them: not to eat carrion, and not to drink wine, and not to speak falsely, and not to engage in fornication. And he said, “With an oath God promised this land to Abraham and his descendants after him forever. And he brought it about as he said in the time when he loved Israel. Truly, you are now the sons of Abraham, and God is fulfilling the promise to Abraham and his descendants on your behalf. Now love the God of Abraham with a single mind, and go and seize your land, which God gave to your father Abraham, and no one will be able to stand against you in battle, because God is with you.”[54]

In other words, we actually have multiple early non-Muslim sources that mention Muhammad, including an Armenian writer from the 660s CE, a Syriac writer from around 660 CE, and another Syriac writer from around 640 CE, all within mere decades of his death: it is only through wishful thinking that the proponents of Muhammad mythicism render these inexpedient testimonies inadmissible.[55]

Finally, a wave of recent scholarship has argued that at least some of the genealogy and tribal relations reported for the 7th Century CE and even earlier are substantially reliable, whilst a recent spate of Arabian epigraphic discoveries has independently confirmed that Muslim reporters and writers of the 8th and 9th Centuries CE accurately remembered the names of some of their 7th-Century ancestors.[56] In other words, the early Arabo-Islamic genealogical tradition seems to have been fairly accurate (at least as far back as the early 7th Century CE)—and, as it happens, the extant Islamic historical sources are unanimous regarding Muhammad’s basic genealogical data: he was the son of ʿAbd Allah and Aminah; he married Khadijah and several others; he was the father of Fatimah; etc.[57] In other words, the existence of Muhammad is attested in a layer of historical material that has been shown to be particularly reliable, adding even more strength to his historicity.

Conclusion

By now, the basic strategy of Muhammad mythicism has become clear: proponents of this view use the problems of the early Islamic historical sources—exposed by the last century and a half of critical scholarship—as an excuse to completely remove these sources from consideration altogether; they speculate that the relevant early non-Muslim sources are all interpolated and thus eliminate these sources as well; they accept the implausible hypothesis that the Quran was only collected and canonised c. 700 CE, thereby nullifying yet another source; and they fill the resulting void, which they themselves have created, with completely implausible interpretations of the meagre inscriptional evidence that remains. In other words: wherever possible, proponents of Muhammad mythicism attempt to remove inexpedient evidence from the equation; and, in every instance, they adopt the least plausible interpretation of the evidence.[58] As things stand, there is no reason to doubt Muhammad’s historical existence: even assuming the worst-case scenario in terms of sources, the assumption of his historicity makes far better sense of the evidence.

Of course, none of this is to say that the picture presented in the extant Islamic sources is accurate per se: the Muhammad who appears therein is clearly highly embellished and distorted in various ways—the Muhammad of faith, so to speak. Still, at least the basic picture therein can be trusted: it is beyond reasonable doubt that Muhammad was a religious leader in Western Arabia at the beginning of the 7th Century CE, whose movement went on to become the religion of Islam.[59]

* * *

Addendum 1: Historians on Historicity

The AcademicQuran subreddit has a post in which the statements of numerous Islamic Studies scholars affirming the historicity of Muhammad are collated. See here:

Addendum 2: Muhammad in pre-Islamic Arabia

There is further evidence for “Muhammad” as a name already before the time of the Prophet. For example, Baladhuri, Ansab al-Ashraf, II, p. 203, lists six men who were reportedly named Muhammad in pre-Islamic Arabia:

- Muhammad b. Sufyan b. Mujashiʿ b. Darim b. Malik b. Hanzalah b. Malik b. Zayd b. Manah b. Tamim.

- Muhammad b. al-Hirmaz (a.k.a. al-Harith) b. Malik b. ʿAmr b. Tamim.

- Muhammad b. Barr b. Turayf b. ʿUtwarah b. ʿAmir b. Layth b. Bakr b. ʿAbd Manah b. Kinanah.

- Muhammad al-Shuwayʿir b. Humran b. Abi Humran al-Juʿfi.

- Muhammad b. ʿUqbah b. Uhayhah b. al-Jallah al-Awsi.

- Muhammad b. Maslamah al-Ansari al-Awsi.

Muhammad b. Durayd (ed. ʿAbd al-Salam Muhammad Harun), al-Ishtiqaq (Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Jil, 1991), pp. 8-9, provides an overlapping but slightly different list:

- Muhammad b. Humran al-Juʿfi al-Shaʿir.

- Muhammad b. Bilal b. Uhayhah b. al-Jallah.

- Muhammad b. Sufyan b. Mujashiʿ b. Darim

- Muhammad b. Maslamah al-Ansari

- Abu Muhammad Masʿud b. Uways b. Asram b. Zayd b. Thaʿlabah

- Muhammad b. Khawli

Of course, these are genealogical reports preserved in much later sources; but the idea that Muhammad was a name used already in pre-Islamic Arabia is now strengthened by ancient Arabian inscriptions, in which mhmd appears as a proper name. This is not necessarily the name “Muhammad” (i.e., other vocalisations are possible, such as Mahmad, Muhmid, etc.), but it is consistent with being “Muhammad” and throws doubt on the already baseless assertion that “Muhammad” was not a name used prior to c. 700 CE.

For one of these inscriptions, see the following Twitter thread:

For others, see the following comment on the AcademicQuran subreddit:

Additionally, the Twitter user @DerMenschensohn (here) has pointed out a possible instance of a feminine “Muḥammadah” in a list of Christian martyrs from Najrān recorded in the Syriac Book of the Himyarites:

https://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/digital/collection/CUA/id/45122

* * *

I owe special thanks to al-Baraa El-Hag, AM, CJ Canton, HM, Mehrab, abcshake, AR, AO, Anthony Wagner, LLH, Marijn van Putten, and QA, for their generous support over on Patreon. Anyone else wishing to financially support this blog can do so over on my Patreon (here) or via my PayPal (here).

For a preliminary podcast version of this blog article, see here.

REFERENCES

[1] Ernest Renan (trans. Ibn Warraq), “Muhammad and the Origins of Islam”, in Ibn Warraq (ed.), The Quest for the Historical Muhammad (Amherst, USA: Prometheus Books, 2000), p. 129.

[2] John C. Lamoreaux, The Early Muslim Tradition of Dream Interpretation (Albany, USA: State University of New York Press, 2002), p. 15.

[3] Keith Lewinstein, “Recent Critical Scholarship and the Teaching of Islam”, in Brannon M. Wheeler, Teaching Islam (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 49.

[4] For various summaries of this scholarship and these problems, see Patricia Crone, Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1980), ch. 1; Francis E. Peters, “The Quest of the Historical Muhammad”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 23, No. 3 (1991), pp. 291-315; Fred M. Donner, Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing (Princeton, USA: The Darwin Press, Inc., 1998), intro.; Gregor Schoeler (ed. James E. Montgomery & trans. Uwe Vagelpohl), The Biography of Muḥammad: Nature and Authenticity (New York, USA: Routledge, 2011), intro.; Herbert Berg, The Development of Exegesis in Early Islam: The Authenticity of Muslim Literature from the Formative Period (Richmond, UK: Curzon Press, 2000), ch. 2; Robert G. Hoyland, “Writing the Biography of the Prophet Muhammad: Problems and Solutions”, History Compass, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2007), pp. 581-602; Stephen J. Shoemaker, “In Search of ʿUrwa’s Sīra: Some Methodological Issues in the Quest for “Authenticity” in the Life of Muḥammad”, Der Islam, Vol. 85, Issue 2 (2011), pp. 257-344; Sean W. Anthony, Muhammad and the Empires of Faith: The Making of the Prophet of Islam (Oakland, USA: University of California Press, 2020), ch. 1; Joshua J. Little, “Patricia Crone and the ‘Secular Tradition’ of Early Islamic Historiography: An Exegesis”, History Compass, Vol. 20, Issue 9 (2022), e12747; etc.

[5] Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, Mohammedanism: Lectures on Its Origin, Its Religious and Political Growth, and Its Present State (New York, USA: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1916), p. 26 (based on a 1914 lecture).

[6] John Burton, “W. MONTGOMERY WATT and M. V. MCDONALD (ed. and tr.): [The History of al-Ṭabarī.] Vol. VI: Muḥammad at Mecca”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 53, No. 2 (1990), p. 328, col. 2.

[7] There was also a tradition of Muhammad mythicism that arose in Soviet scholarship, summarised in Ibn Warraq, “Studies on Muhammad and the Rise of Islam: A Critical Survey”, in Ibn Warraq (ed.), The Quest for the Historical Muhammad (Amherst, USA: Prometheus Books, 2000), p. 49, and Michael Kemper, “The Soviet Discourse on the Origin and Class Character of Islam, 1923-1933”, Die Welt des Islams, Vol. 49, Issue 1 (2009), pp. 1-48. However, this is a completely different tradition—with a different set of arguments—from the one that is under consideration in the present article.

[8] Yehuda D. Nevo & Judith Koren, Crossroads to Islam: The Origins of the Arab Religion and the Arab State (Amherst, USA: Prometheus Books, 2003), p. 11.

[9] Karl-Heinz Ohlig, “Forward: Islam’s “Hidden” Origins”, in Karl-Heinz Ohlig & Gerd-Rüdiger Puin (eds.), The Hidden Origins of Islam: New Research into Its Early History (Amherst, USA: Prometheus Books, 2010), p. 8.

[10] Id., “Shedding Light on the Beginnings of Islam”, in Karl-Heinz Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam: A Critical Reconstruction Based on Contemporary Sources (Amherst, USA: Prometheus Books, 2013), pp. 10-11.

[11] Hans Jansen, “The historicity of Muhammad, Aisha and who knows who else”, trykkefrihed.dk (16th/May/2011): https://www.trykkefrihed.dk/blog/335/The-historicity-of-Muhammad-Aisha-and-who-knows-who-else.htm.

[12] Id., “Forward”, in Robert B. Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist? An Inquiry into Islam’s Obscure Origins (Wilmington, USA: ISI Books, 2012), p. x.

[13] Robert B. Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist? An Inquiry into Islam’s Obscure Origins, revised & expanded edition (New York, USA: Bombardier Books, 2021), p. 148.

[14] Ibid., e.g., pp. 6-7, 64, 87, 108, 112, 150, 259.

[15] For example, in the YouTube interview cited below, Spencer unequivocally states: “In the case of Muhammad, there is no evidence that any such person existed. He is a creation of various factions that created the Arab Empire for their own goals.”

[16] E.g., Patricia Crone & Michael A. Cook, Hagarism: The making of the Islamic world (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1977), ch. 1; Crone, Slaves on Horses, p. 15; Michael A. Cook, Muhammad (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 74; Patricia Crone, “What do we actually know about Mohammed?”, Open Democracy (10th/June/2008): https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/mohammed_3866jsp/.

[17] Chase F. Robinson, “Islamic Historical Writing, Eighth through the Tenth Centuries”, in Sarah Foot & Chase F. Robinson (eds.), The Oxford History of Historical Writing, Volume 2: 400–1400 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 263-264.

[18] For example, a search of phrases such as “Muhammad did not exist” and “Muhammad never existed” on X.com (née Twitter.com) will reveal numerous expressions of this view. For some other notable online expressions thereof (with views variously ranging from the hundreds to the hundreds of thousands and even, in the last case, one million), see: Jay Smith & Hatun Tash, “Did Muhammad exist?”, YouTube (9th/February/2021): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NwmVAyrV1Gc; David Fitzgerald, “Is the Founder of Your Religion Imaginary?”, YouTube (12th/May/2021): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-6a9kHPGoIs [@31:23]; id., “The Evolution of World Religions”, YouTube (21st/August/2021): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lcceQyGIUkk [@59:58]; Jay Smith & al-Fadi, “DID MUHAMMAD EXIST? “Nope”, here’s why! (#1)”, YouTube (13th/May/2021): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zTJ2QR9ayyw; Robert Spencer, “The Truth About Muhammad”, YouTube (2nd/February/2022): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oiVFGmCKEAA [@58:18]. Such Muhammad mythicism was also widely publicised in the following news article: Andrew Higgins, “Professor Hired for Outreach to Muslims Delivers a Jolt”, The Wall Street Journal (15th/November/2008): https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB122669909279629451. (All of these websites were accessed on 7th/September/2023.)

[19] E.g., Chase F. Robinson, “Early Islamic History: Parallels and Problems”, in Hugh G. M. Williamson (ed.), Understanding the History of Ancient Israel (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 87-102; Daniel Birnstiel, “The Emergence of Islam: No Prophet Named Muhammad?”, Qantara.de (16th/August/2007): https://en.qantara.de/content/the-emergence-of-islam-no-prophet-named-muhammad; Michael Marx (interviewed) “Did Muhammad Ever Really Live?”, SPIEGEL Online (18th/September/2008): https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/dispute-among-islam-scholars-did-muhammad-ever-really-live-a-579052.html; Gregor Schoeler (ed. James E. Montgomery & trans. Uwe Vagelpohl), The Biography of Muḥammad: Nature and Authenticity (New York, USA: Routledge, 2011), pp. 11, 14; Andrew Rippin, “The Qurʾān in Context: Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qurʾānic Milieu. Edited by Angelika Neuwirth, Nicolai Sinai, and Michael Marx”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 131, No. 3 (2011), 470-473; Fred M. Donner, “The historian, the believer, and the Qurʾān”, in Gabriel S. Reynolds (ed.), New Perspectives on the Qurʾān: The Qurʾān in its historical context 2 (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2011), p. 28; Jonathan E. Brockopp, “Interpreting Material Evidence: Religion at the “Origins of Islam””, History of Religions, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2015), pp. 121-147.

[20] Nevo & Koren, Crossroads, intro.; Ohlig, “Forward”, in Ohlig & Puin (eds.), The Hidden Origins of Islam, pp. 8-9; id., “Shedding Light”, in Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam, pp. 10-13; Jansen, “The historicity of Muhammad”; Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, esp. chs. 1-2. Not all of these works directly cite this scholarship, but all of them cite some of the problems raised thereby.

[21] Nevo & Koren, Crossroads, pp. 4, 11, and part III more generally; Ohlig, “Forward”, in Ohlig & Puin (eds.), The Hidden Origins of Islam, pp. 8, 12; Jansen, “Forward”, in Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, p. xi; Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, esp. ch. 12.

[22] Jansen, “The historicity of Muhammad”.

[23] Nevo & Koren, Crossroads, pp. 8, 114, 211-212, 230, 254-255; Ohlig, “Evidence of a New Religion”, in Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam, pp. 196, 205; Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, ch. 2.

[24] Nevo & Koren, Crossroads, pp. 208-210; Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, ch. 2.

[25] See below.

[26] Nevo & Koren, Crossroads, pp. 11-13, 272-273; Ohlig, “Forward”, in Ohlig & Puin (eds.), The Hidden Origins of Islam, pp. 8-9; Jansen, “The historicity of Muhammad”; Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, ch. 2.

[27] Nevo & Koren, Crossroads, part III, ch. 3; Ohlig, “Forward”, in Ohlig & Puin (eds.), The Hidden Origins of Islam, pp. 9-10; id., “Shedding Light”, in Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam, pp. 10-11; Popp, “From Ugarit to Sāmarrāʾ”, in Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam, pp. 60 ff.; Ohlig “From muḥammad Jesus to Prophet of the Arabs”, in Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam, passim; Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, ch. 3.

[28] Jansen, “The historicity of Muhammad”.

[29] Ibid.

[30] For some partial surveys of the available sources, see ʿAbd al-ʿAziz b. Wali Allah al-Dihlawi (trans. Akram Nadwi & Aisha Bewley), The Garden of the Ḥadīth Scholars: Bustān al-Muḥaddiṯīn, 2nd ed. (London, UK: Turath Publishing, 2018); Cook, Muhammad, pp. 62-63; Gautier H. A. Juynboll, Muslim tradition: Studies in chronology, provenance and authorship of early ḥadīth (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983), ch. 1; Patricia Crone, Roman, provincial and Islamic law: The origins of the Islamic patronate (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987), ch. 2; Muhammad Z. Siddiqi (ed. Abd al-Hakim Murad), Ḥadīth Literature: Its Origin, Development and Special Features (Cambridge, UK: Islamic Texts Society, 1993); Aisha Y. Musa, “Ḥadīth Studies”, in Clinton Bennett (ed.), The Bloomsbury Companion to Islamic Studies (London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013); Anthony, Muhammad, part II.

[31] In addition to the sources cited above, which are largely proto-Sunni, we also have various Shiʿi, Ibadi, and other sources; see Michael A. Cook, Early Muslim Dogma: A Source-critical Study (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1981), passim; Crone, Roman, provincial and Islamic law, ch. 2; Najam I. Haider, The Origins of the Shīʿa: Identity, Ritual, and Sacred Space in Eighth-Century Kūfa (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 36-38, 75.

[32] Likewise, see Hurgronje, Mohammedanism, pp. 26 ff.; Donner, Narratives, pp. 25 ff.

[33] For example, even Khalifah b. Khayyat, a Basran scholar who was sympathetic to the Umayyads and indifferent to the Hashimids and their early political causes, reported that Muhammad was a Hashimid; see Khalifah b. Khayyat (ed. Suhayl Zakkar), Tabaqat Khalifah b. Khayyat (Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Fikr, 1993), p. 26. For Khalifah’s politico-theological views, see Carl Wurtzel, in Khalifah b. Khayyat (trans. Carl Wurtzel), Khalifa ibn Khayyat’s History on the Umayyad Dynasty (660–750) (Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2015), intro. Likewise, see the pro-Umayyad Syrian scholar ʿAli b. al-Hasan b. ʿAsakir (ed. ʿUmar b. Gharamah al-ʿAmrawi), Taʾrikh Madinat Dimashq, vol. 3 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Fikr, 1995), p. 3. For Ibn ʿAsakir’s politico-theological views, see Aaron M. Hagler, The Echoes of Fitna: Accumulated Meaning and Performative Historiography in the First Muslim Civil War (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2023), p. 77.

[34] For a similar kind of argument (in favour of the authenticity of the so-called “Constitution of Medina”), see Harry Munt, The Holy City of Medina: Sacred Space in Early Islamic Arabia (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 56.

[35] See for example the references given in Stephen J. Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad’s Life and the Beginnings of Islam (Philadelphia, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), pp. 99-106, and Little, “Patricia Crone”.

[36] See the references given in Joshua J. Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age: A Study in the Evolution of Early Islamic Historical Memory”, PhD dissertation (University of Oxford, 2023), ch. 6.

[37] Robert G. Hoyland, Seeing Islam as others saw it: A survey and evaluation of Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian writings on early Islam (Princeton, USA: The Darwin Press, Inc., 1997), excursus F; Jeremy Johns, “Archaeology and the History of Early Islam: The First Seventy Years”, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 46, No. 4 (2003), pp. 411-436; Fred M. Donner, Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam (Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press, 2010), pp. 205, 208, 210, 233-235.

[38] For the increasingly overriding authority, and increasing citation, of Muhammad in the domain of legal doctrine and norms from the 7th to 9th Century CE, see: Joseph F. Schacht, The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1950), passim; Michael A. Cook, Early Muslim Dogma: A Source-critical Study (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1981), esp. ch. 3; Juynboll, Muslim tradition, ch. 1; Patricia Crone & Martin Hinds, God’s Caliph: Religious authority in the first centuries of Islam (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986), chs. 3-5; Gautier H. A. Juynboll, “Some new ideas on the development of sunna as a technical term in early Islam”, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, Vol. 10 (1987), pp. 98-118; Harald Motzki (trans. Marion H. Katz), The Origins of Islamic Jurisprudence: Meccan Fiqh before the Classical Schools (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2002), pp. 126-127, ch. 4; Ersilia Francesca, “The Concept of sunna in the Ibāḍī School”, in Adis Duderija (ed.), The Sunna and Its Status in Islamic Law: The Search for a Sound Hadith (Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 97-115; Harald Motzki, Reconstruction of a Source of Ibn Isḥāq’s Life of the Prophet and Early Qurʾān Exegesis: A Study of Early Ibn ʿAbbās Traditions (Piscataway, USA: Gorgias Press, 2017), intro.; Adam Gaiser, “Ballaghanā ʿan an-Nabī: Early Basran and Omani Ibāḍī understandings of sunna and siyar, āthār and nasab”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 83, No. 3 (2020), pp. 437-448; etc.

For example, see Yaʿqub b. Sufyan al-Fasawi (ed. Akram Diyaʾ al-ʿUmari), Kitab al-Maʿrifah wa-al-Taʾrikh, vol. 2 (Medina, KSA: Maktabat al-Dar, 1989), p. 15 ← Abu ʿUmar Hafs b. ʿUmar (Basran; d. 840 CE) ← Ziyad b. al-Rabiʿ al-Yahmadi (Basran; d. 801 CE) ← Salih al-Dahhan (Basran; fl. mid-8th C. CE): “I never heard Jabir—meaning Ibn Zayd—say, ‘the Messenger of God said,’ yet the young men around here are saying ‘the Messenger of God said’ twenty times an hour. I never knew of Jabir having narrated from the Messenger of God more than fifteen or sixteen Hadith, or thereabouts.” Note: according to Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Dhahabi (ed. Shuʿayb al-Arnaʾut et al.), Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 4, 2nd ed. (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1982), pp. 481-482, Jabir b. Zayd (d. 711-712 or 721-722 CE) “was the scholar of the people of Basrah in his time” and “[one] of the greatest of the students of Ibn ʿAbbas.”

For another view of the reason for Muhammad’s increasing importance over time, in the context of Donner’s general model of early Islam, see Donner, Muhammad, pp. 205-206.

[39] See also Robinson, “Early Islamic History”, in Williamson (ed.), Understanding the History of Ancient Israel, p. 103.

[40] Nevo & Koren, Crossroads, pp. 260 ff.; Popp, “The Early History of Islam”, in Ohlig & Puin (eds.), The Hidden Origins of Islam, passim; Popp, “From Ugarit to Sāmarrāʾ”, in Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam, passim; Ohlig, “From muḥammad Jesus to Prophet of the Arabs”, in Ohlig (ed.), Early Islam, passim; Spencer, Did Muhammad Exist?, ch. 2.

[41] Adapted from Hoyland, Seeing Islam, p. 693. I owe thanks to Mohsen Goudarzi and Marijn van Putten for insights regarding the phrase allāh w kbr kabīrā, which Hoyland interpreted as “God, magnify [Him] greatly” (allāh wa-kabbir kabīran), but which is probably actually “God is very great” (allāh akbar kabīran). In other words, the initial hamzah of the word akbar has been softened to a wāw to bridge the ending of allāh (i.e., allāhu, with a nominative ḍammah) and the beginning of akbar (i.e., the fatḥah on the hamzah), i.e., “allāhuwakbar“.

[42] In general, see also Birnstiel, “The Emergence of Islam”.

[43] See the sources just cited.

[44] Birnstiel, “The Emergence of Islam”; Schoeler (trans. Vagelpohl), The Biography of Muḥammad, p. 14.

[45] Brockopp, “Interpreting Material Evidence”, pp. 131-133.

[46] For more on this method, see Harald Motzki, “Dating Muslim Traditions: A Survey”, Arabica, Tome 52, Issue 2 (2005), pp. 204-253; A. Kevin Reinhart, “Juynbolliana, Gradualism, the Big Bang, and Ḥadīth Study in the Twenty-First Century”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 130, No. 3 (2010), pp. 413-444; Pavel Pavlovitch, The Formation of the Islamic Understanding of Kalāla in the Second Century AH (718–816 CE): Between Scripture and Canon (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2015), pp. 22 ff.; Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age”, ch. 1.

[47] Andreas Görke & Gregor Schoeler, Die ältesten Berichte über das Leben Muhammads: Das Korpus ʿUrwa ibn az-Zubair (Princeton, USA: The Darwin Press, Inc., 2008) [= The Earliest Writings on the Life of Muḥammad: The ʿUrwa Corpus and the Non-Muslim Sources (Berlin, Germany: Gerlach Press, 2024)].

[48] Donner, Muhammad and the Believers, p. 228.

[49] E.g., Julius Wellhausen (trans. Wolfgang Behn), Muhammad’s Constitution of Medina, in Muhammad and the Jews of Medina (Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany: K. Schwarz, 1975), passim; Arent J. Wensinck (trans. Wolfgang Behn), Muhammad and the Jews of Medina (Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany: K. Schwarz, 1975), passim; Moshe Gil, “The Constitution of Medina: A Reconsideration”, Israel Oriental Studies, Vol. 4 (1974), pp. 44-66; Crone & Cook, Hagarism, p. 7; Robert B. Serjeant, “The Sunnah Jāmiʿah, Pacts with the Yaṯẖrib Jews, and the Taḥrīm of Yaṯẖrib: Analysis and Translation of the Documents Comprised in the So-Called ‘Constitution of Medina’”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 41, Issue 1 (1978), p. 8; Crone, Slaves on Horses, p. 7; Crone, Roman, provincial and Islamic law, p. 32; Hoyland, Seeing Islam, pp. 548-549; Michael Lecker, The “Constitution of Medina”: Muḥammad’s First Legal Document (Princeton, USA: The Darwin Press, Inc., 2004), p. ix, intro, and appendix A; Moshe Gil, Jews in Islamic Countries in the Middle Ages (Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2004), p. 22; Saïd A. Arjomand, ‘The Constitution of Medina: A Sociolegal Interpretation of Muhammad’s Acts of Foundation of the Umma’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 41, No. 4 (2009), p. 555; Donner, Muhammad and the Believers, p. 227; Shoemaker, “In Search of ʿUrwa’s Sīra”, p. 275; Andreas Görke, “Prospects and Limits in the Study of the Historical Muhammad”, in Nicolet Boekhoff-van der Voort, Kees Versteegh, & Joas Wagemakers (eds.), The Transmission and Dynamics of the Textual Sources of Islam: Essays in Honour of Harald Motzki (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2011), p. 147; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, p. 206; Munt, The Holy City of Medina, pp. 54-56; Hiroyuki Yanagihashi, Studies in Legal Hadith (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2019), p. 442; Michael Lecker, “The Constitution of Medina”, in Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, & Everett Rowson (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, online edition).

[50] For these and other considerations, see Friedrich Schwally, “Betrachtungen über die Koransammlung des Abu Bekr”, in Gotthold Weil (ed.), Festschrift Eduard Sachau: zum siebzigsten Geburtstage gewidmet von Freunden und Schülern (Berlin, Germany: Georg Reimer, 1915), pp. 324-325; Alford T. Welch, “al-Ḳurʾān: 3. History of the Ḳurʾān after 632”, in Clifford E. Bosworth, Emeri J. van Donzel, Bernard Lewis, & Charles Pellat (eds.), The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, vol. 5 (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 1986), p. 405, col. 2; Hossein Modarressi, “Early Debates on the Integrity of the Qurʾān: A Brief Survey”, Studia Islamica, Number 77 (1993), pp. 13-14; Fred M. Donner, Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing (Princeton, USA: The Darwin Press, Inc., 1998), into. & ch. 1; Harald Motzki, “The Collection of the Qurʾān: A Reconsideration of Western Views in Light of Recent Methodological Developments”, Der Islam, Vol. 78, Issue 1 (2001), pp. 1-34; Behnam Sadeghi & Uwe Bergmann, “The Codex of a Companion of the Prophet and the Qurʾān of the Prophet”, Arabica, Tome 57 (2010), pp. 364 ff.; Gregor Schoeler, “The Codification of the Qurʾan: A Comment on the Hypotheses of Burton and Wansbrough”, in Angelika Neuwirth, Nicolai Sinai, & Michael Marx (eds.), The Qurʾān in Context Historical and Literary Investigations into the Qurʾānic Milieu (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010), pp. 779-794; Nicolai Sinai, “When did the consonantal skeleton of the Quran reach closure? Part I”, Bulletin of SOAS, Vol. 77, Issue 2 (2014), pp. 273-292; id., “When did the consonantal skeleton of the Quran reach closure? Part II”, Bulletin of SOAS, Vol. 77, Issue 2 (2014), pp. 509-521; Nicolai Sinai, The Qurʾan: A historical-critical introduction (Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2017), pp. 45-47; Marijn van Putten, “‘The Grace of God’ as evidence for a written Uthmanic archetype: the importance of shared orthographic idiosyncrasies”, Bulletin of SOAS, Vol. 82, Issue 2 (2019), pp. 272-274, 279, 287; Seyfeddin Kara, “Contemporary Shiʿi Approaches to the History of the Text of the Qurʾān”, in Munʾim Sirry (ed.), New Trends in Qurʾānic Studies: Text, Context, and Interpretation (Atlanta, USA: Lockwood Press, 2019), pp. 123-124; Hythem Sidky, “On the Regionality of Qurʾānic Codices”, Journal of the International Qurʾanic Studies Association, Vol. 5 (2020), pp. 182-183; Nicolai Sinai, “The Christian Elephant in the Meccan Room: Dye, Tesei, and Shoemaker on the Date of the Qurʾān”, Journal of the International Qur’anic Studies Association, Vol. 9, Issue 1 (2024), pp. 57-118; Joshua J. Little, “On the Historicity of ʿUthmān’s Canonization of the Qur’an”, Journal of the International Qur’anic Studies Association (forthcoming). Cf. Robinson, “Early Islamic History”, in Williamson (ed.), Understanding the History of Ancient Israel, pp. 96, 104.

[51] See the following references.

[52] Stephen J. Shoemaker, A Prophet has appeared: The rise of Islam through Christian and Jewish eyes (Oakland, USA: University of California Press, 2021), p. 61. See also Andrew Palmer, The Seventh Century in West-Syrian Chronicles (Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 1993), pp. 5 ff.; Hoyland, Seeing Islam, pp. 118-120; James Howard-Johnston, Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 63-64; Michael P. Penn, When Christians First Met Muslims: A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam (Oakland, USA: University of California Press, 2015), pp. 27-28; Anthony, Muhammad and the Empires of Faith, p. 40.

[53] Shoemaker, A Prophet has appeared, pp. 129-130. See also Hoyland, Seeing Islam, pp. 182 ff.; Chase F. Robinson, “The Conquest of Khūzistān: A Historiographical Reassessment”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 67, No. 1 (2004), pp. 14-15; Howard-Johnston, Witnesses to a World Crisis, pp. 126 ff.; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, pp. 33 ff.; Penn, When Christians First Met Muslims, pp. 47-49.

[54] Shoemaker, A Prophet has appeared, p. 63. See also Hoyland, Seeing Islam, pp. 124 ff.; Howard-Johnston, Witnesses to a World Crisis, pp. 70-74; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, pp. 199 ff.; Anthony, Muhammad, pp. 195-196; Tim W. Greenwood, “Sasanian Echoes and Apocalyptic Expectations: A Re-Evaluation of the Armenian History attributed to Sebeos”, Le Muséon, Vol. 115, Issues 3-4 (2002), p. 389.

[55] See also Donner, “The historian, the believer, and the Qurʾān”, p. 28; and Robinson, “Early Islamic History”, in Williamson (ed.), Understanding the History of Ancient Israel, p. 103.

[56] See the references given in Little, “Patricia Crone”.

[57] E.g., Muhammad b. Ishaq [& Yunus b. Bukayr] (ed. Suhayl Zakkar), Kitab al-Siyar wa-al-Maghazi (Damascus, Syria: Dar al-Fikr, 1978), part 1; ʿAbd al-Malik b. Hisham (ed. Ferdinand Wüstenfeld), Kitab Sirat Rasul Allah / Das Leben Muhammed’s, 2 vols. in 1 (Göttingen, Germany: Dieterichsche Universitäts-Buchhandlung, 1858-1860), pp. 100 ff., 119 ff., 587; Maʿmar b. Rashid [& ʿAbd al-Razzaq b. Hammam] (ed. Sean W. Anthony), The Expeditions: An Early Biography of Muḥammad (New York, USA: New York University Press, 2014), pp. 6 ff.; Muhammad b. Saʿd (ed. Eugen Mittwoch), Biographien Muhammeds, seiner Gefährten und der späteren Träger des Islams, Band I, Theil I: Biographie Muhammeds bis zur Flucht (Leiden, the Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1905), pp. 58 ff., 83 ff.; Ahmad b. Yahya al-Baladhuri (ed. Suhayl Zakkar & Riyad Zirikli), Kitab Jumal min Ansab al-Ashraf, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Fikr, 1997), pp. 87-88, 108 ff.; ibid., II, pp. 23 ff., 29 ff.; Muhammad b. Jarir al-Tabari (ed. Michael J. de Goeje and reviewed by Pieter de Jong), Annales quos scripsit Abu Djafar Mohammed ibn Djarir at-Tabari, vol. 3 (Leiden, the Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1882-1885), pp. 1073 ff., 1127 ff.; Ahmad b. al-Husayn al-Bayhaqi (ed. ʿAbd al-Muʿti Qalʿaji), Dalaʾil al-Nubuwwah wa-Maʿrifat Ahwal Sahib al-Shariʿah, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dar al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 1988), pp. 71 ff., 102 ff.; ibid., II, pp. 68 ff.; Fasawi, al-Maʿrifah wa-al-Taʾrikh, III, pp. 319 ff.

[58] For a similar assessment, see Brockopp, “Interpreting Material Evidence”, p. 133.

[59] See also the following Twitter thread for more of my thoughts on our prospects for recovering the historical Muhammad: https://x.com/IslamicOrigins/status/1654840294888833025