In the course of my investigation of a certain corpus of exegetical hadiths, I happened to come across the following report in the Tafsīr of al-Ṭabarī:

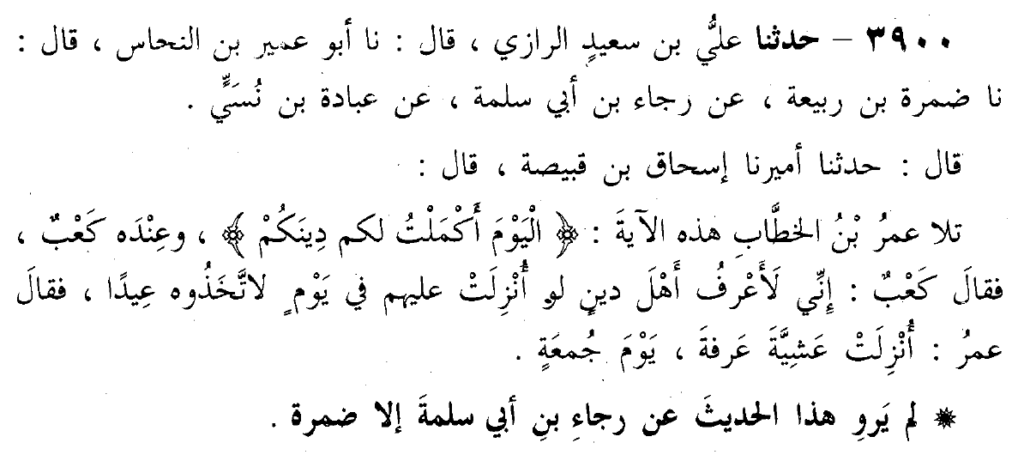

Yaʿqūb b. ʾIbrāhīm related to me—he said: “Ibn ʿUlayyah related to us—he said: “Rajāʾ b. ʾabī Salamah related to us—he said: “ʿUbādah b. Nusayy, reported to us—he said: “Our emir, ʾIsḥāq—ʾAbū Jaʿfar [al-Ṭabarī] said: ʾIsḥāq is Ibn Ḵarašah—related to us from Qabīṣah, who said: “Kaʿb said: “Were [it the case] that other than this community was sent this verse, then assuredly, they would have paid attention to the day on which it was revealed to them and made it into a holiday on which to convene. Then ʿUmar said: “Which verse, O Kaʿb?” Then he said: “Today, I have perfected your religion for you” [Q. 5:3]. Then ʿUmar said: “I knew the day upon which it was revealed, and the place where it was revealed: [it was] a Friday and the Day of ʿArafah, and both of them—in praise of God—are a holiday for us.””””””[1]

Most of the tradents cited in the isnad at the beginning of this hadith are easily discernible:

- Kaʿb = al-ʾAḥbār, a famous Jewish convert and tābiʿ who came from Madinah to the Levant with ʿUmar; d. 32-35/652-656.[2]

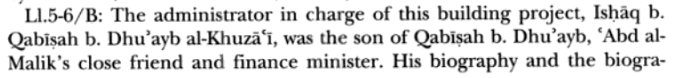

- Qabīṣah = Ibn Ḏuʾayb, a Madinan tābiʿ who moved to the Levant and become influential at the caliphal court under ʿAbd al-Malik; d. 700s CE.[3]

- ʿUbādah b. Nusayy = Governor of Jordan under ʿUmar II, and Judge of Tiberias; d. 118/736.[4]

- Rajāʾ b. ʾabī Salamah = a Basran who settled in Jerusalem; he transmitted from ʿUbādah b. Nusayy; d. 161/777-778.[5]

And so on, so forth. All of these tradents were fairly easy to identify, save one: ʾIsḥāq. Who is this ambiguous tradent?

ʾIsḥāq is positioned after Qabīṣah and before ʿUbādah in the isnad, which immediately gives us a sense of when and where he was operating: the Umayyad Levant. Additionally, ʿUbādah calls ʾIsḥāq “our emir”, and al-Ṭabarī clarifies: “ʾIsḥāq is Ibn Ḵarašah”. With these clues, I began my quest.

Firstly, I checked whether the Islamweb page links to a bio on him. It does not.

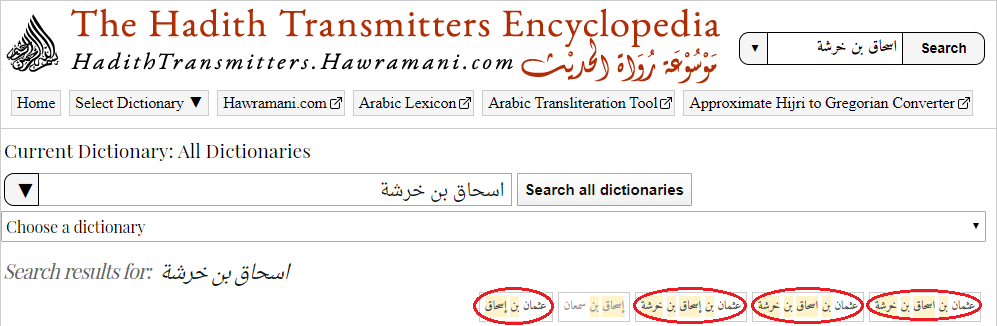

Secondly, I searched for “إسحاق بن خرشة” in the hadithtransmitters.hawramani.com database (which synthesises most of the major Islamic Hadith-related biographical dictionaries and prosopographies), but it yielded no entries thereon.

Thirdly, I searched for “Ishaq b. Kharashah” (and similar wordings) on Google Books, just in case he is ever mentioned in English scholarship—but he is not.

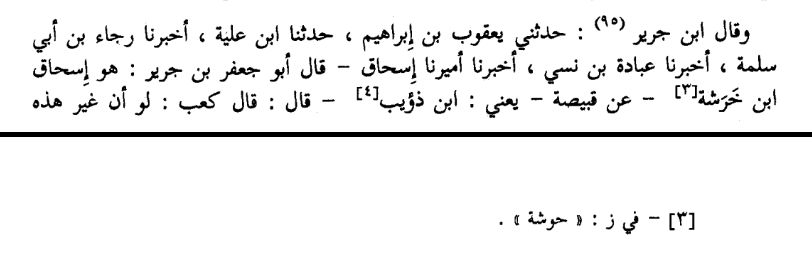

Fourthly, I also searched for “إسحاق بن خرشة” on Google Books, yielding an interesting result: according to the editors of the Muʾassasat Qurṭubah edition of al-Ṭabarī’s Tafsīr, there is a variant of the text that has “Ḥwšah” (حوشة) instead of “Ḵarašah” (خرشة).

However, a search of “إسحاق بن حوشة” on Google, Hawramani, and the Shamela database of Arabic texts yielded zero hits, so I quickly discarded “Ḥwšah” as an obvious scribal error and resumed my search for someone named “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah”. I searched for “إسحاق بن خرشة” on Shamela, but this yielded no instances of this name independently of al-Ṭabarī’s Tafsīr and citations thereof.

I began to think that ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, the ʾIsḥāq cited in my isnad, was a true ‘unknown’ (majhūl). I was not the first to think so—for example, Shaykh Muṣṭafá al-ʿAdawī, the editor of the Dār Balinsiyyah edition of Ibn Ḥumayd’s Muntaḵab, notes the following in a footnote, in relation to this hadith:

And [as for] this aforementioned isnad, its tradents are reliable, except for ʾIsḥāq: I am not aware of his biography. [Nevertheless,] I was satisfied concerning him with ʿUbādah’s statement: “Our emir related to us…”[6]

I was not satisfied with this, however: I wanted to know *who* ʾIsḥāq is, not whether he is ‘reliable’ (ṯiqah). Thus, my quest continued.

All the while, I noticed throughout my search that another figure kept popping up most of the time: ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, who, coincidentally, also transmitted from Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb.

I began to suspect that some kind of error had occurred, and that ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah was intended in the isnad. But what sort of scenario would that entail? Did the isnad start with “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq” and then lose “ʿUṯmān b.” in the course of transmission, only for al-Ṭabarī to make the further error of identifying him as “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah” rather than “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah”?

This seems implausible to me. Are we really to suppose that al-Ṭabarī saw “ʾIsḥāq” in this isnad, thought of ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, and then mistakenly omitted “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq” when he wrote his comment, “He is Ibn Ḵarašah”? Or, are we to suppose that al-Ṭabarī originally wrote, “He is ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah”, but that a later scribe omitted “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq” when he copied al-Ṭabarī’s comment? In other words, did exactly the same strange error occur twice, first with an earlier tradent (omitting “ʿUṯmān”) and secondly with al-Ṭabarī or a later scribe (again omitting “ʿUṯmān”)?

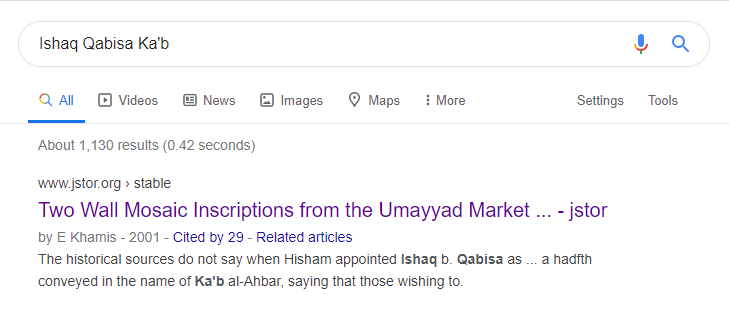

I was not satisfied with this, so in a final attempt, I started googling “Ishaq” in combination with other names from the isnad (in English), hoping for a hit. Finally, when I googled “Ishaq Qabisa Ka’b”, I noticed the following:

Curious, I searched on Google Books for more information about this person named “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah”, until something in Moshe Sharon’s Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (vol. 2) caught my eye…

Firstly, ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah was the son of none other than Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb! Secondly, this ʾIsḥāq is variously reported as director of Sick-Care Bureau under Caliph al-Walīd I, governor of Jordan under Caliph Hišām, and director of the Alms Bureau and manager of royal estates in Jordan under Hišām.

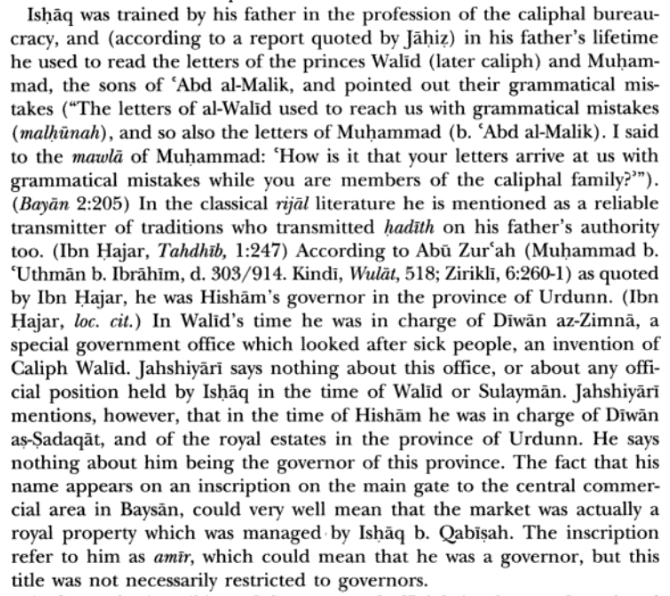

His name even appears on an inscription in Baysān (in Palestine) from 738 CE, which refers to him as “emir”. This is significant because ʿUbādah calls the ʾIsḥāq of the isnad under investigation “our emir”!

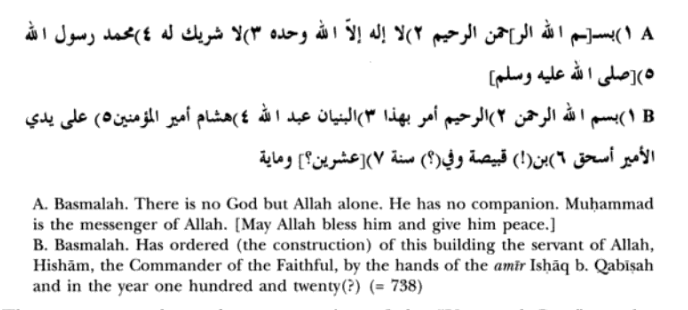

Thirdly, a search for “إسحاق بن قبيصة” on Hawramani revealed that ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah transmitted Hadith to none other than ʿUbādah b. Nusayy!

All of this led me to conclude that there is no scribal error (of the kind outlined above) in this isnad, no missing “ʿUṯmān” in the text. Instead, the error was evidently on the part of al-Ṭabarī, who wrongly claimed that ʾIsḥāq was Ibn Ḵarašah. ʾIsḥāq = Ibn Qabīṣah.

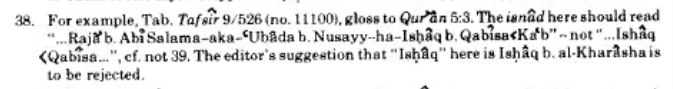

And, as it turns out, I am not the first to come to this conclusion! Upon further investigation (now that I knew to search for “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah”), I discovered a few other academic discussions on this exact issue. For example, Fred Donner addresses this exact hadith and points out that ʾIsḥāq = Ibn Qabīṣah. He also says: “The editor’s suggestion that “Isḥāq” here is Isḥāq b. al-Ḵarāsha is to be rejected.”[7]

Maḥmūd Muḥammad Šākir, editor of the Maktabat Ibn Taymiyyah edition of al-Ṭabarī’s Tafsīr, likewise identified ʾIsḥāq as Ibn Qabīṣah, based on his being known as (1) a transmitter from and son of Qabīṣah, (2) a transmitter to ʿUbādah, and (3) an emir in the Levant.

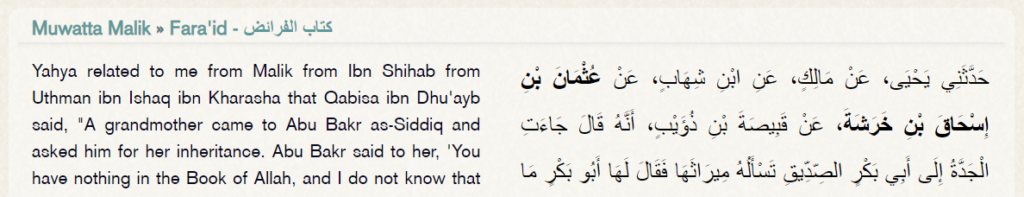

And as for “ʾIsḥāq”, verily, ʾAbū Jaʿfar [al-Ṭabarī] claimed that he is Ibn Ḵarašah. But I did not find “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah” amongst transmitters, nor amongst governors. And as for “Ibn Ḵarašah”, he is “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah (with an a-vowel on the letter Ḵ and on the letter R) al-Qurašī”. Al-Zuhrī transmitted from him, and no transmission from him is mentioned for ʿUbādah b. Nusayy, nor was he an emir. And his genealogy is as was transmitted by Ibn Saʿd: he is “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾabī Ḵarašah b. ʿAmr b. Rabīʿah b. al-Ḥāriṯ b. Ḥabīb b. Jaḏīmah b. Mālik b. Ḥisl b. ʿĀmir b. Luʾayy.” His genealogy is also [transmitted by] al-Muṣʿab in Nasab Qurayš. He said: “Ibn Šihāb [al-Zuhrī] transmitted from him, from Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb, the hadith of the grandmother,” which is the hadith that the people of the four sunnahs transmitted, from the transmission-path of Mālik in the Muwaṭṭaʾ, with his transmission from “Ibn Šihāb, from ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, from Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb.”

I do not doubt that ʾAbū Jaʿfar has erred. He desired the identification of “ʾIsḥāq” in this isnad of his, so he arrived at the error of “Ibn Ḵarašah”, for he is “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah”, not “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah”.

As for “ʾIsḥāq” in this report, I do not doubt that he is “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb”, who transmits it from his father “Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb”.

And that, firstly, is because “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb al-Ḵuzāʿī” transmits from his father, and from Kaʿb al-ʾAḥbār.

Secondly, [because] “ʿUbādah b. Nusayy” al-ʾUrdunnī, the judge of Tiberias, is mentioned in his biography, and [it is mentioned] that he transmits from ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb.

Thirdly, [because] “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb” is the who was an emir. He was Hišām’s governor of Jordan, just as ʾAbū Zurʿah al-Dimašqī said. And Ibn Sumayʿ said: “He was [in charge] of the Bureau of Illness during the days of al-Walīd.” And ʿUbādah b. Nusayy is a judge from amongst the judges of Jordan, as we mentioned.

So, who? There is no doubt thereon with me, that “ʾIsḥāq” in this isnad is ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb, who transmits from his father, and that ʾAbū Jaʿfar [al-Ṭabarī] has erred in his elucidation and was confused.[8]

ʾAkram Ziyādah al-Fālūjī, author of a biographical dictionary of al-Ṭabarī’s sources, similarly notes that “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah” is unknown, and that his name might be a corruption/misspelling of ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah, since the latter transmitted from his father and to ʿUbādah. ʾAkram also notes the possibility that the name is a corruption of ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, who also transmitted from Qabīṣah. Finally, ʾAkram cites al-Turkī’s conclusion that ʾIsḥāq = Ibn Qabīṣah.

ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, from the Third [generation]; I did not know of him, nor did Shaykh Šākir Qibilī know of him. I was not aware of him [being referenced] anywhere else in the Tafsīr except [in] this report. I fear that there is a corruption here, or a misspelling of his name, since the one from whom he (ʿUbādah) transmitted is ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah, who transmits from his father. However, he is from the Sixth [generation], and he remained [alive] up until after the year 120 [i.e., post-737-738 CE], and the one transmitting from him (ʿUbādah) is from the Third [generation], having died in the year 118 [i.e., 736-7 CE]. And [there is] also a possibility that there is an omission in the name of the transmitter from him, and [that] he is [actually] ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah. He is amongst those who transmit from Qabīṣah, as in the Taʾrīḵ Dimašq, the Tahḏīb al-Kamāl, and others. [It is] also known that ʿUṯmān is from the Fifth [generation]. And since he [i.e., ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah] transmitted from the Syrians, and the Syrians transmitted from him, I have searched in the Taʾrīḵ Dimašq, but I did not find any biography about him. Nothing remained except to adhere to the text of al-Ṭabarī, especially [since it is the case] that the great scholar Ibn Kaṯīr has attributed it in his Tafsīr to the author [i.e., al-Ṭabarī] and cited it as a sanad and a matn like his. Herewith, this ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah is an unknown emir and obscure in transmission. Then I saw [that] Doctor al-Turkī has cited the report in his edition, and he determined that he is ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah. And see the final word thereon in my edition of the Tafsīr, and see the biography of ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah after a number of biographies.[9]

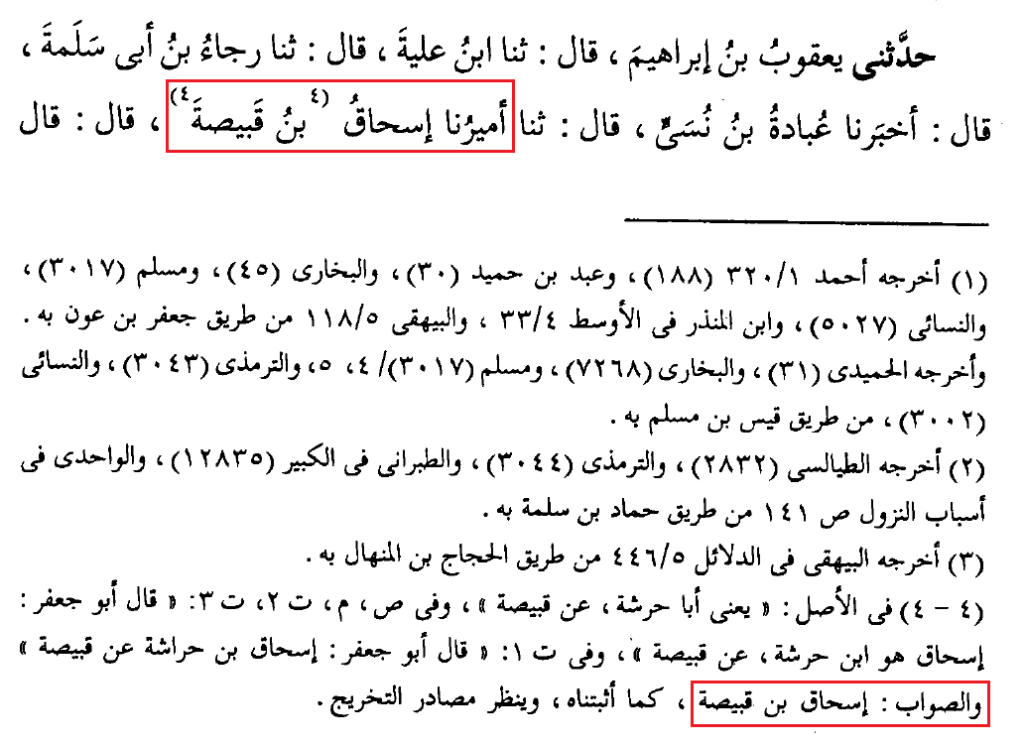

ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbd al-Muḥsin al-Turkī, editor of the Dār Hajar edition of al-Ṭabarī’s Tafsīr, was so confident in this conclusion that he outright emended the text to “Isḥāq b. Qabīṣah”, replacing the corruption and al-Ṭabarī’s comment:

In the attached footnote, al-Turkī added:

In the original: “…meaning, ʾAbū Ḥarašah, from Qabīṣah…” And in Ṣ., M., T. 2, T. 3: “ʾAbū Jaʿfar said: “ʾIsḥāq (who is Ibn Ḥarašah), from Qabīṣah…”” And in T. 1: “ʾAbū Jaʿfar said: “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḥarāšah, from Qabīṣah.”” And the correct [version] is: “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah,” as we demonstrated.[10]

Finally, I noticed that Ibn Ḥajar mentioned this hadith in his Fatḥ al-Bārī, not just from al-Ṭabarī’s Tafsīr, but also from al-Ṭabarānī’s ʾAwsaṭ and Musaddad’s Musnad.

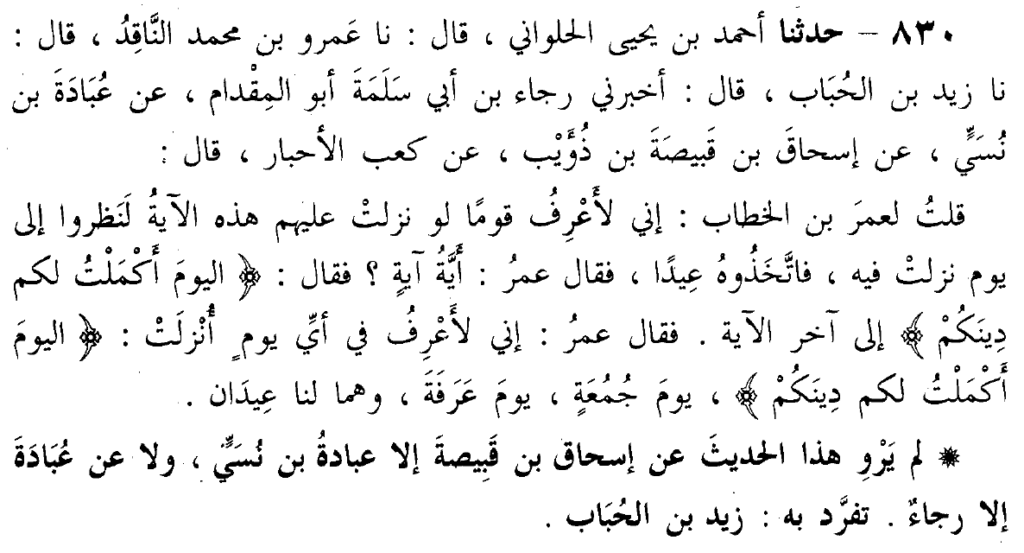

The Musnad appears to be non-extant, but when I turned to the ʾAwsaṭ, I discovered something interesting: al-Ṭabarānī cites two variants of this hadith, and in both instances, ʾIsḥāq is explicitly called “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah”!

This makes sense: al-Ṭabarānī hailed from Tiberias in Palestine, so it stands to reason that he would know more about Levantine transmitters than al-Ṭabarī.

Because I was specifically searching for “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah”, my prior searches had not brought al-Ṭabarānī’s two variants to light. It was only when I checked Ibn Ḥajar, who mentions “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah” and also cites al-Ṭabarānī, that I found them!

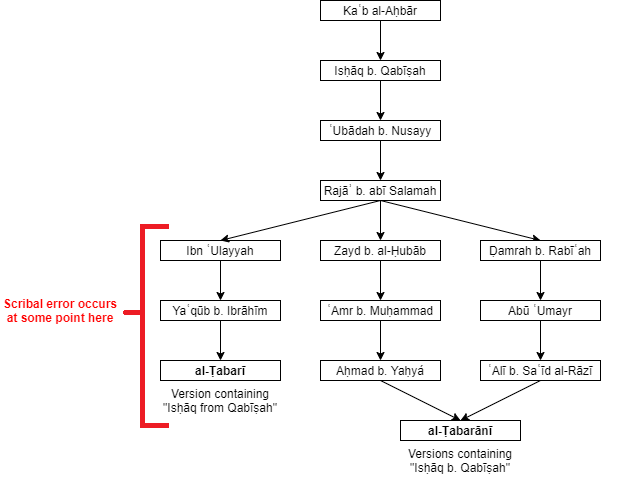

But there was something more: al-Ṭabarānī’s isnads differ from al-Ṭabarī’s in a key respect!

- Al-Ṭabarī’s version: Rajāʾ—ʿUbādah—ʾIsḥāq—Qabīṣah—Kaʿb

- Al-Ṭabarānī’s versions: Rajāʾ—ʿUbādah—ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah—Kaʿb

It is not merely the case that al-Ṭabarānī specifies that ʾIsḥāq is Ibn Qabīṣah; he also omits Qabīṣah altogether as a transmitter, and instead has ʾIsḥāq transmitting directly from or about Kaʿb! In other words, al-Ṭabarānī’s isnad may be ‘disconnected’ (mursal/munqaṭiʿ), since Kaʿb died in the 650s CE and ʾIsḥāq died at some time after 738 CE. It seems questionable to me that ʾIsḥāq studied under and transmitted from Kaʿb directly.

Might we then posit that al-Ṭabarī deliberately altered his version, placing Qabīṣah between ʾIsḥāq and Kaʿb in order to make the isnad more believable? I doubt it. If al-Ṭabarī deliberately turned “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah” into “ʾIsḥāq from Qabīṣah”, then he would have known who ʾIsḥāq was in the first place. Yet, he was confused about ʾIsḥāq’s identity.

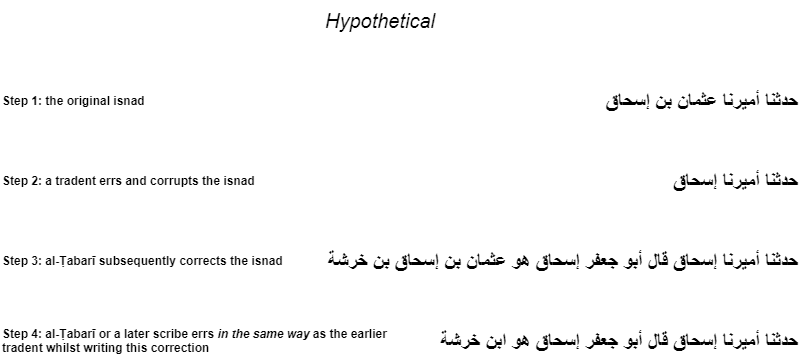

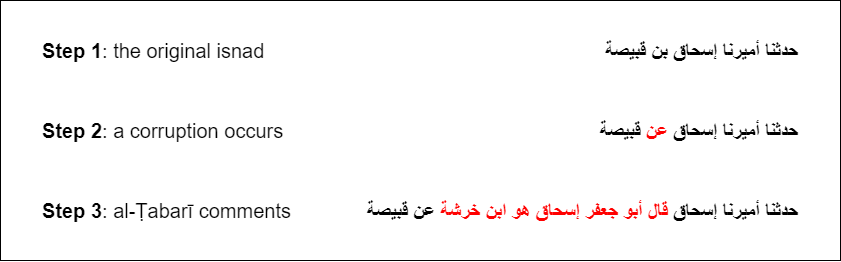

The alternative, and the answer to all of this confusion, is obvious. What we have here is simple scribal error on the part of al-Ṭabarī, or perhaps his immediate source, Yaʿqūb b. ʾIbrāhīm, or perhaps his source’s source, Ibn ʿUlayyah.

Al-Ṭabarī (or whoever) evidently misread and/or miswrote “our emir ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah related to us” (حدثنا أميرنا إسحاق بن قبيصة) as “our emir ʾIsḥāq related to us from Qabīṣah” (حدثنا أميرنا إسحاق عن قبيصة). The letter Bāʾ became the letter ʿAyn, thus corrupting the word “son” (بن) into the word “from” (عن).

But this does not explain why al-Ṭabarī subsequently identified ʾIsḥāq as Ibn Ḵarašah, rather than Ibn Qabīṣah. After all, even the corrupted isnad would still immediately suggest Ibn Qabīṣah, since the isnad now depicts ʾIsḥāq as a transmitter from Qabīṣah.

As I pondered this, I was able to refine my Arabic searches, until I discovered another scholarly treatment on this exact topic: the introductory notes by Hišām b. ʿAlī al-Saʿīdnī & Nādir Muṣṭafá Maḥmūd to their edition of Ibn Ḥajar’s Nukat. Once again, my reasoning had been pre-empted! In addition to noting that ʾIsḥāq was a Levantine governor and the son of Qabīṣah, these editors had also noted al-Ṭabarānī’s variants and hypothesised the scribal error in al-Ṭabarī’s version:

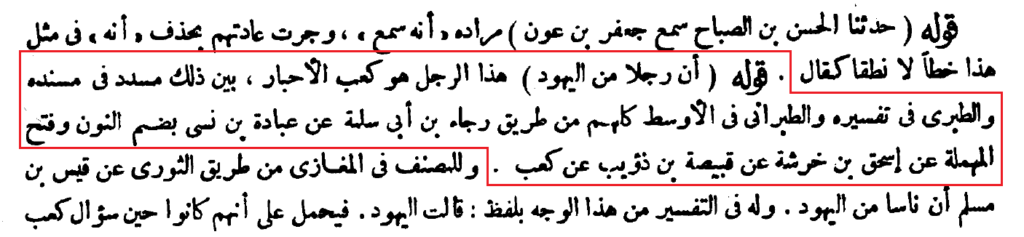

With hadith # 45 from Ṣaḥīḥ al-Buḵārī (Kitāb al-ʾĪmān, Bāb Ziyādat al-ʾĪmān wa-Nuqṣāni-hi), Ibn Ḥajar said (regarding the statement of al-Buḵārī “…that a man from the Jews…”): “This man is Kaʿb al-ʾAḥbār. Musaddad made that clear in his Musnad, [as did] al-Ṭabarī in his Tafsīr and al-Ṭabarānī in al-ʾAwsaṭ. All of them [obtained this hadith] from the transmission-path of Rajāʾ b. ʾabī Salamah, from ʿUbādah b. Nusayy ([spelled] with a u-vowel on the letter N and an a-vowel on the undotted [letter S]), from ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, from Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb, from Kaʿb…”

Then, when he turned his attention to the hadith in al-Nukat, he changed the name of ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah. He said: “…from ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb, from Kaʿb…”

And what he mentioned in al-Nukat, it is the correct [version] concerning the name of the transmitter.

And the cause of the first error [in Ibn Ḥajar’s Fatḥ al-Bārī] is that the Hadith obtained with al-Ṭabarī in his Tafsīr regarding Verse 3 from Sūrat al-Māʾidah, from the transmission-path of Ibn ʿUlayyah: “…from Rajāʾ b. ʾabī Salamah, from ʿUbādah b. Nusayy, who said: “Our emir ʾIsḥāq”—ʾAbū Jaʿfar [al-Ṭabarī] said: “ʾIsḥāq is Ibn Ḵarašah—“related to us, from Qabīṣah, who said…”” Then he recounted [the rest of] the hadith.

Then, Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī recounted the hadith in Fatḥ al-Bārī just as it was with Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, which is an error, as we mentioned.

Perhaps the cause of that error [in al-Ṭabarī’s version] is that the name with Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī was misspelled “ʾIsḥāq from Qabīṣah”, replacing “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah”, i.e.: “son” was misspelled as “from”. Then Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī wanted the specification of this ʾIsḥāq, so he perceived that he is Ibn Ḵarašah. [But this] is a specification of error also, because Ibn Ḵarašah, who transmits from Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb, his name is ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah. He is not ʾIsḥāq, his father, who is the one intended [by al-Ṭabarī]. And he is also called “ʿUṯmān b. Ḵarašah”, and he is the transmitter of the hadith of ʾAbū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq concerning the bequeathing of the grandmother.

As for ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah b. Ḏuʾayb (which is the correct name for the transmitter), he was Hišām b. ʿAbd al-Malik’s governor over Jordan.

Moreover, the hadith has been cited correctly [i.e., with “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah”] by al-Ṭabarānī in al-ʾAwsaṭ; and likewise, by Ibn ʿAsākir in his Taʾrīḵ, from the transmission-path of Musaddad b. Musarhad.[11]

In short, it turns out that I had reinvented the wheel: several other scholars had already done most of my detective work several years ago!

This revelation could be considered annoying or depressing, since my research on ʾIsḥāq ended up being superfluous. On the other hand, I find it reassuring that my conclusions are corroborated, and indeed, that those more familiar with the source-material than I have followed a similar reasoning process and come to the same conclusion.

That said, I disagree with one of the suggestions by some of the aforementioned scholars. I do not think that al-Ṭabarī confused “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah” for “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah.” Instead, I think that al-Ṭabarī reasoned as follows: when a son cites his father in an isnad, the usual formula (at least in my experience) is either “X from his father” or “X said: “from my father””; therefore, the fact that the (corrupted) isnad has “ʾIsḥāq from Qabīṣah” rather than “ʾIsḥāq from his father” makes it seem as though this ʾIsḥāq was *not* the son of Qabīṣah.

But why then did al-Ṭabarī posit him as Ibn Ḵarašah? My Guess is: because ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah is a known transmitter from Qabīṣah, al-Ṭabarī concluded that the ʾIsḥāq in this isnad was ʿUṯmān’s (otherwise unknown) father, who could plausibly have met and transmitted from Qabīṣah as well.

I do not think al-Ṭabarī confused “ʿUṯmān b. ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah” for “ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah” – I think he intended his otherwise-unknown father. I think that this was the only way he could make sense of the corrupted isnad in front of him, without access to al-Ṭabarānī’s uncorrupted versions.

To sum up:

- ʾIsḥāq = Ibn Qabīṣah, as is explicitly preserved in al-Ṭabarānī’s versions of the isnad.

- A scribal error turned “ʾIsḥāq b. Qabīṣah” into “ʾIsḥāq from Qabīṣah” in al-Ṭabarī’s version.

- Al-Ṭabarī wrongly inferred that ʾIsḥāq = Ibn Ḵarašah.

Thus ends the mystery of ʾIsḥāq b. Ḵarašah, solved many times over!

* * *

For the original Twitter thread upon which this article is based, see:

https://twitter.com/IslamicOrigins/status/1244656530105999360?s=20

[1] Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (ed. Maḥmūd Muḥammad Šākir & ʾAḥmad Muḥammad Šākir), Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī: Jāmiʿ al-Bayān ʿan Taʾwīl ʾÂy al-Qurʾān, vol. 9 (Cairo, Egypt: Maktabat Ibn Taymiyyah, n. d.), p. 526, # 11100.

[2] Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar ʾAʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 3, 2nd ed. (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1982), pp. 489 ff.

[3] Discussed in Sean W. Anthony, Muhammad the Empires of Faith: The Making of the Prophet of Islam (Oakland, USA: University of California Press, 2020), 95, 133.

[4] Ḏahabī (ed. ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar, V, pp. 323-324.

[5] ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Ḥātim, Kitāb al-Jarḥ wa-al-Taʿdīl, vol. 2 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār ʾIḥyāʾ al-Turāṯ al-ʿArabiyy, 1952), p. 502.

[6] Muṣṭafá al-ʿAdawī, in ʿAbd b. Ḥumayd (ed. Muṣṭafá al-ʿAdawī), al-Muntaḵab min Musnad ʿAbd b. Ḥumayd, vol. 1 (Riyadh, KSA: Dār Balansiyyah, 2002), p. 86 n.

[7] Fred M. Donner, ‘The Problem of Early Arabic Historiography in Syria’, in Muhammad A. Bakhit (ed.), Proceedings of the Second Symposium on the History of Bilād al-Shām during the Early Islamic Period up to 40 A.H./640 A.D.: The Fourth International Conference on the History of Bilād al-Shām (Amman, Jordan: University of Jordan, 1987), 10, n. 38.

[8] Šākir, in Ṭabarī (ed. Šākir & Šākir), Tafsīr, IX, p. 527, n. 2.

[9] ʾAkram Ziyādah al-Fālūjī, al-Muʿjam al-Ṣaḡīr li-Ruwāt al-ʾImām Ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, vol. 1 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār Ibn ʿAffān, n.d.), p. 43, # 210.

[10] ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbd al-Ḥasan al-Turkī, in Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (ed. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbd al-Ḥasan al-Turkī), Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī: Jāmiʿ al-Bayān ʿan Taʾwīl ʾÂy al-Qurʾān, vol. 8 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār Hajar, 2001), p. 87, n. 4.

[11] Hišām b. ʿAlī al-Saʿīdnī & Nādir Muṣṭafá Maḥmūd, ‘Tarājuʿāt Ibn Ḥajar ʿan Baʿḍ Ijtihādāt fī Fatḥ al-Bārī’, in Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī (ed. Hišām b. ʿAlī al-Saʿīdnī & Nādir Muṣṭafá Maḥmūd), al-Nukat ʿalá Ṣaḥīḥ al-Buḵārī wa-yalī-hi al-Tajrīd ʿalá al-Tanqīḥ, vol. 1 (Cairo, Egypt: al-Maktabat al-ʾIslāmiyyah, 2005), pp. 11-12.