Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān (d. 198/813) was an important early Hadith scholar in Basrah and one of the founders of proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism, the movement or methodology that ultimately produced the Sunnī Hadith canon. For example, the Syrian Sunnī Hadith scholar Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (d. 748/1348) summarised the history of Hadith criticism as follows:

Great scholars have composed numerous works concerning the impugning [of tradents] and the establishing of [their] reliability (al-jarḥ wa-al-taʿdīl), ranging [in their compositional tendencies] from [brief] summarisation to [lengthy] elaboration. The first of those whose pronouncements thereon were collected was the scholar about whom ʾAḥmad b. Ḥanbal declared: “I never saw with my eyes [anyone else] like Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān.”[1]

There is a famous quotation attributed to Yaḥyá, which is often cited to contextualise the fabrication of Hadith amongst early Muslims: “I have not seen the pious (al-ṣāliḥīn), in any regard, [being] more dishonest (ʾakḏab) than they [are] in regards to Hadith.”[2]

The Baghdadian Sunnī Hadith scholar ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʿAlī al-Jawzī (d. 597/1201) cited this report to exemplify “a group who fabricated hadiths on the awakening of desire [for God’s rewards] and the instilling of fear [of God’s punishments] (al-tarḡīb wa-al-tarhīb), in order to incite the masses—so they claim—towards goodness (li-yaḥaṯṯū al-nās bi-zamʿi-him ʿalá al-ḵayr), and to keep them away from evil (wa-yazjurū-hum ʿan al-šarr).”[3]

Likewise, Ignaz Goldziher cited this report from Yaḥyá to illustrate the phenomenon of pious fabrication in early Hadith, as follows:

So far there have been repeated references to the tendentious fabrications of traditions during the first century of Islam and in the course of our further account we shall continue to meet this method of producing religious sources. It is a matter for psychologists to find and analyse the motives of the soul which made such forgeries acceptable to pious minds as morally justified means of furthering a cause which was in their conviction a good one. The most favourable explanation which one can give of these phenomena is presumably to assume that the support of a new doctrine (which corresponded to the end in view) with the authority of Muhammed was the form in which it was thought good to express the high religious justification of that doctrine. The end sanctified the means. The pious Muslims made no secret of this. A reading of some of the sayings of the older critics of the tradition or of the spreaders of traditions themselves will easily show what was the prevailing opinion regarding the authenticity of sayings and teachings handed on from pious men. ʿĀṣim [sic] al-Nabīl, a specialist in the study of tradition (who died in Baṣra in 212 aged 90), said openly: ‘I have come to the conclusion that a pious man is never so ready to lie as in matters of the ḥadīth.’ The same has also been said by his Egyptian [sic] contemporary Yaḥyā b. Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān (d. 192).[4]

There are multiple versions of this report, however—which version, if any, can be traced all the way back to Yaḥyá himself? By applying an isnad-cum-matn analysis, we can answer this question.

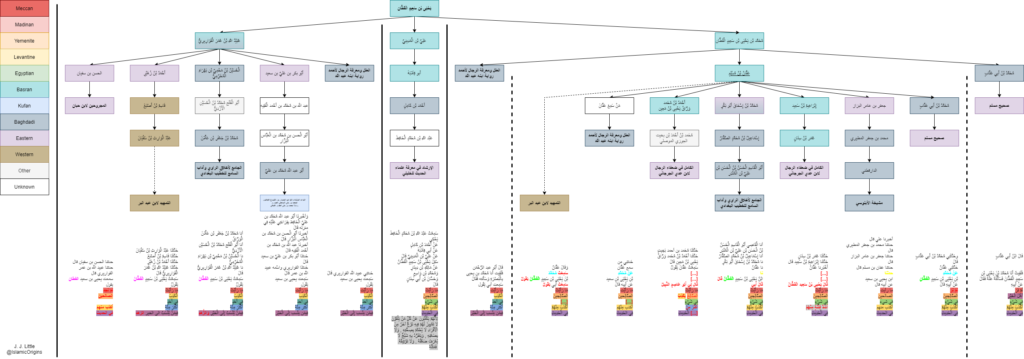

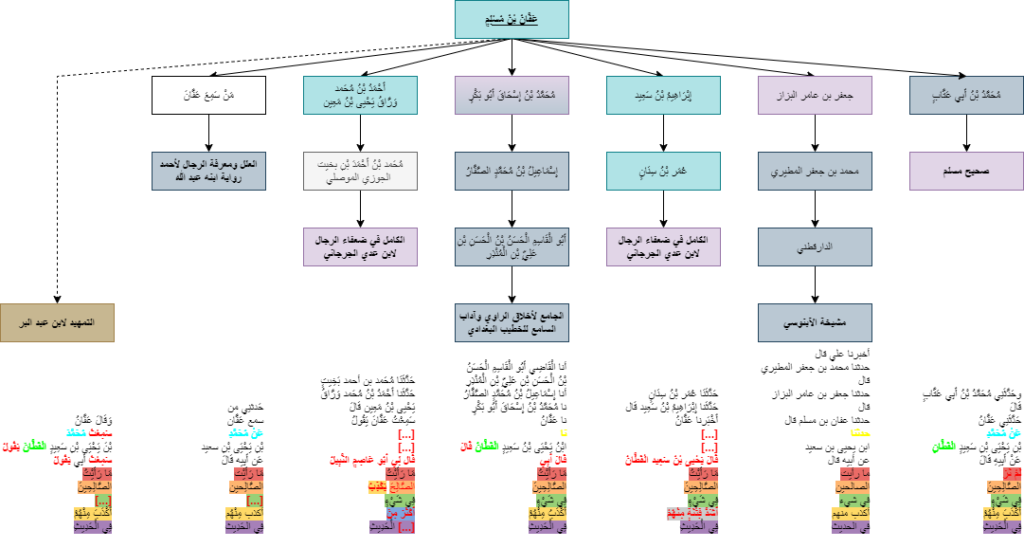

To begin with, most versions cite to the Basran “partial common link” (PCL) ʿAffān b. Muslim (d. 220/835), and although there is considerable textual variation therebetween and even some errors or interpolations in the isnads, a consistent, underlying urtext can be detected vis-à-vis most other versions.

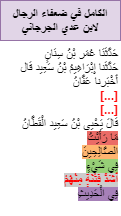

The following can thus be attributed to ʿAffān:

Ibn Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd [al-Qaṭṭān] related to us, from his father, who said: “I have not seen the pious (mā raʾaytu al-ṣāliḥīn), in any regard (fī šayʾ), [being] more dishonest than they [are] in regards to Hadith (ʾakḏab min-hum fī al-ḥadīṯ).”

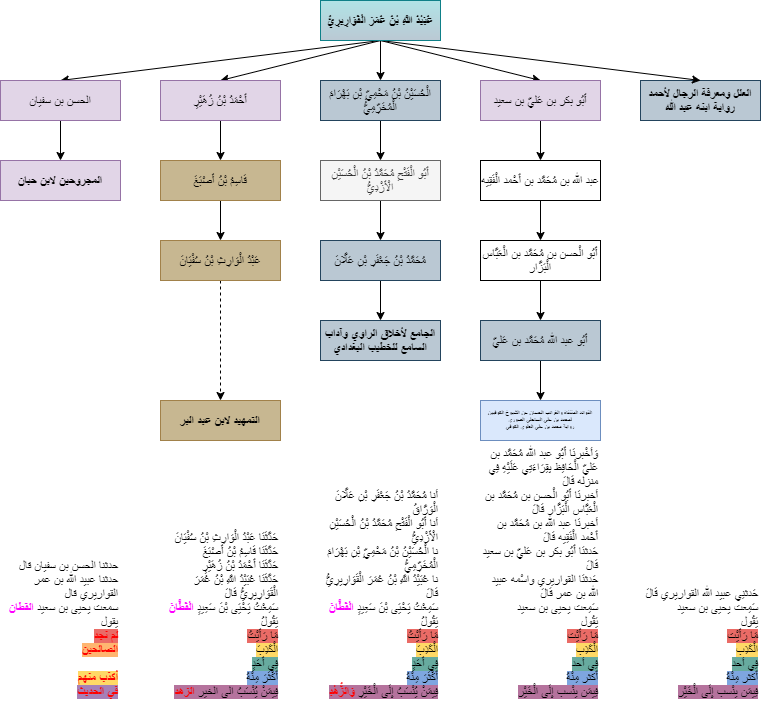

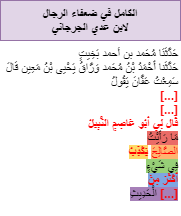

Another set of versions cite the Basro-Baghdadian PCL ʿUbayd Allāh b. ʿUmar al-Qawārīrī (d. 235/850), and although there is again considerable textual variation and even contamination in the matns, a distinctive redaction is again discernible.

The following can thus be attributed to ʿUbayd Allāh:

I heard Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd [al-Qaṭṭān] say: “I have not seen dishonesty (mā raʾaytu al-kaḏib) in anyone (fī ʾaḥad) more than he to whom goodness is attributed (ʾakṯar min-hu fī-man yunsabu ʾilá al-ḵayr).”

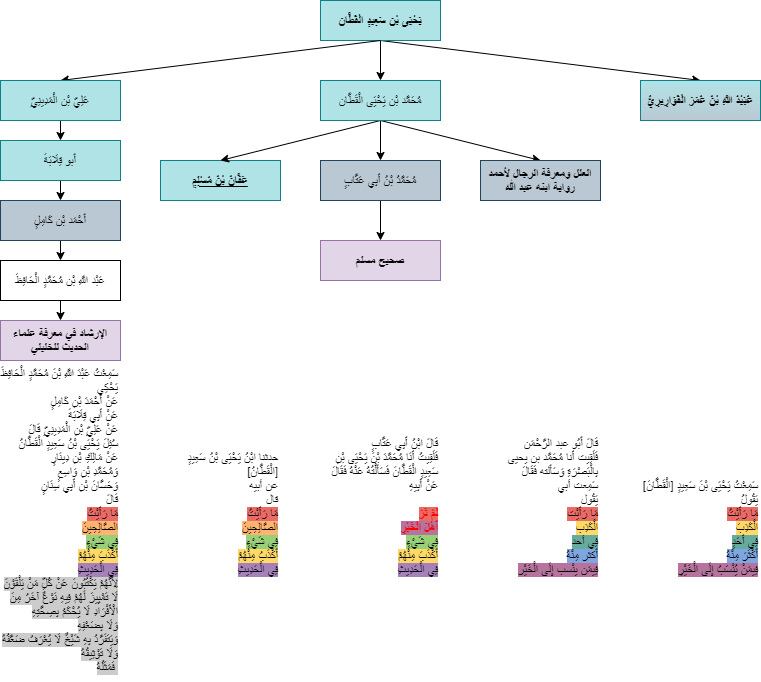

All of this leaves us with the following transmissions from Yaḥyá:

The material overall clearly embodies a common underlying ur-redaction on the topic of ‘those who are most dishonest’, which is consistent with their common ascription to Yaḥyá, the “common link” (CL). But which version best represents Yaḥyá’s original wording? Did Yaḥyá speak of “the pious” (al-ṣāliḥīn) and Hadith, or did he speak of “he to whom goodness is attributed” (man yunsabu ʾilá al-ḵayr), or perhaps both?

Both versions are multiply attested, but ʿAffān’s version from Ibn Yaḥyá (in contrast to ʿAbd Allāh’s) is directly corroborated by another recorded by Muslim (despite some variant wordings therein), and both are corroborated from Yaḥyá (in contrast to ʿUbayd Allāh’s version) by another recorded by al-Ḵalīlī. Thus, at the very least, the following can likely be traced all the way back to Yaḥyá:

I have not seen the pious (mā raʾaytu al-ṣāliḥīn), in any regard (fī šayʾ), [being] more dishonest than they [are] in regards to Hadith (ʾakḏab min-hum fī al-ḥadīṯ).

Beyond the intrinsic interest of Yaḥyá’s statement (which implies that pious fabrication was ubiquitous in early Hadith), this tradition is of interest given its variation. Yaḥyá was an extremely late CL (operating at the end of the 8th Century CE), yet even in the transmissions from him, there are notable interpolations, contaminations, and/or errors.

For example, one version, recorded by Ibn ʿAdī, shortens the isnad (by omitting Ibn Yaḥyá therefrom) and changes an element in the matn (from ʾakḏab min-hum to ʾašadd fitnah min-hum):

Another version, again recorded by Ibn ʿAdī, changes the report’s source from Yaḥyá to the Basran traditionist ʾAbū ʿĀṣim al-Nabīl (d. 211-214/826-830), whilst also borrowing some distinctive wordings from the transmissions from ʿUbayd Allāh (placing the k-ḏ-b root in an earlier position and replacing ʾakḏab with ʾakṯar):

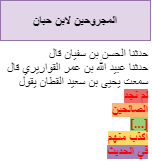

Another version, recorded by Ibn Ḥibbān, replaces the distinctive matn of ʿUbayd Allāh (with kaḏib near the beginning, fī ʾaḥad ʾakṯar in the middle, and man yunsabu ʾilá al-ḵayr at the end) with that of ʿAffān (with al-ṣāliḥīn near the beginning, ʾakḏab in the middle, and al-ḥadīṯ at the end):

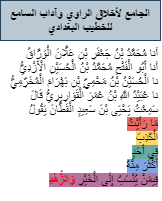

Another version, recorded by al-Ḵaṭīb al-Baḡdādī, inserts an extra detail (wa-al-zuhd) at the very end of the matn, thereby altering its meaning to some degree by making it refer specifically to ascetics:

Thus, in addition to the content of the report warning against fabrication in Hadith, the very transmission of this content also serves as a warning, if not of outright fabrication, then at least of the interpolation, contamination, and error that can occur in early Hadith transmission. This is especially the case given that the interpolations, contaminations, and errors in question must have occurred between the PCLs and the extant collections, or in other words, from the early 9th Century CE onwards, in the era of systematic and written transmission.

In short, by using an ICMA, an interesting report about the ubiquity of pious fabrication in Hadith can be plausibly traced back to Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān (d. 198/813), one of the founders of proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism. However, this ICMA also reveals frequent interpolations, contaminations, and/or errors that occurred in the transmission of this report, as late as the 9th Century CE onwards. Thus, both this report’s content and its transmission serve as a caution regarding false ascription in Hadith.

* * *

I owe special thanks to ʿAlī Jabbār, for helping to clarify certain textual points, and to Yet Another Student, for his generous support over on my Patreon.

For the original Twitter thread upon which this article is based, see:

https://twitter.com/IslamicOrigins/status/1590326716182192130?s=20

[1] Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (ed. ʿAlī Muḥammad al-Bijāwī), Mīzān al-Iʿtidāl fī Naqd al-Rijāl, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Maʿrifah, n. d.), p. 1.

[2] Variously recorded in: the Ṣaḥīḥ of Muslim; the ʿIlal of ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾAḥmad; the Majrūḥīn of Ibn Ḥibbān; the Kāmil of Ibn ʿAdī; the ʾIršād of al-Ḵalīlī; the Mašyaḵah of al-ʾÂbanūsī; the Jāmiʿ of al-Ḵaṭīb al-Baḡdādī; the Tamhīd of Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr; and the Fawāʾid of al-Ṣūrī.

[3] ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʿAlī al-Jawzī (ed. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Muḥammad ʿUṯmān), Kitāb al-Mawḍūʿāt, vol. 1 (Madinah, KSA: al-Maktabah al-Salafiyyah, 1966), p. 39.

[4] Ignaz Goldziher (ed. Samuel M. Stern and trans. Christa R. Barber & Samuel M. Stern), Muslim Studies, Volume 2 (Albany, USA: State University Press of New York, 1971), 54-55. Note: “ʿĀṣim” should be emended to “ʾAbū ʿĀṣim”, and “Egyptian” should be emended to “Basran”.