There were diverse approaches or attitudes towards Hadith in the first few Islamic centuries, ranging from uncritical acceptance, to critical acceptance, to skepticism, to wholesale rejection. Ultimately, it was the critical acceptance of Hadith—the approach or methodology known as “Hadith criticism” (naqd al-ḥadīṯ)—that won out amongst the proto-Sunnī Hadith movement (ʾaṣḥāb al-ḥadīṯ) from the early 9th Century CE onward, who used it to produce what would become “the six books” (al-kutub al-sittah) of the classical Sunnī Hadith canon, alongside many other semi-canonical and non-canonical collections.[1]

The practitioners of this method were known as “Hadith critics” (al-jahābiḏah and nuqqād al-ḥadīṯ), and relied upon the collation of transmissions and the establishing of corroboration to evaluate tradents—known as “the discipline of the impugning [of tradents] and the establishing of [their] reliability” (ʿilm al-jarḥ wa-al-taʿdīl)—in order to authenticate (taṣḥīḥ) or impugn (taḍʿīf) hadiths.

This methodology is to be contrasted with the approaches and methods of the early rivals of the proto-Sunnī Hadith movement—above all, the early rationalists (ʾaṣḥāb al-kalām) of Iraq, such as the proto-Muʿtazilah, who only accepted hadiths that were super-widely transmitted (mutawātir), and/or those with content that conformed to the Quran, common sense, and consensus (ʾijmāʿ). The same distinction applies to the jurists of the early regional legal traditions (ʾaṣḥāb al-raʾy), including the proto-Ḥanafiyyah (embodying the local tradition of Kufah) and the proto-Mālikiyyah (embodying the local tradition of Madinah), who relied upon local practice (ʿamal/ʾamr/sunnah) and local consensus (ʾijmāʿ) in their evaluation of Hadith, and who often resorted to legal reasoning (raʾy) in lieu of Hadith, all of which was anathema to the proto-Sunnī Hadith movement.[2]

Proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism is even to be contrasted with later classical Sunnī Hadith scholarship, which combined an adherence to the judgements of the earlier Hadith critics with some methods and concepts inherited from the early rationalists—above all, explicit content criticism and the concept of mutawātir.[3] Indeed, given the rise and spread of canonical Hadith collections from the 9th to the 11th Centuries CE and the consequent decline of individual Hadith transmission (as opposed to the scribal transmission of entire collections), subsequent Sunnī scholars lost the ability to intensively collate and compare transmissions in the manner of their proto-Sunnī forebears.[4] The classical scholars thus had little choice but to rely upon the conclusions of their forebears and/or adopt alternative methods of analysis (e.g., those of the rationalists), although attempts to apply or revive the original Hadith-critical methodology certainly continued across the classical period.[5]

This disjuncture is sharper still when it comes to modern Sunnī Hadith scholarship, which has not only inherited the semi-rationalist synthesis of the classical Sunnī Hadith tradition (including concepts like mutawātir), but also seems to have largely lost sight of the actual methodology of the proto-Sunnī Hadith critics altogether.[6] Consequently, the modern Sunnī approach to evaluating Hadith often amounts to little more than looking up and mechanically applying the judgements of past scholars recorded in Hadith-related prosopography, without understanding the methods or reasoning that produced these judgements in the first place.[7]

The secular Hadith scholarship of the past century was similarly ignorant of the actual methodology of the proto-Sunnī Hadith critics, inheriting from the classical and modern Sunnī tradition the same misconceptions discussed below.[8] However, the last few decades have seen a resurgence in understanding on the part of both secular Hadith scholars and some of their traditional Sunnī counterparts,[9] and it is upon this recent scholarship that the present article stands.

The Methodology of Proto-Sunnī Hadith Criticism

What was the method of the proto-Sunnī Hadith critics, the method that was used to authenticate Hadith and produce the Sunnī Hadith canon? What exactly made a tradent “reliable” (ṯiqah) and a hadith “sound” (ṣaḥīḥ)?

Firstly, contrary to common misconception, the Hadith critics almost never consulted biographical information on tradents, such as birth-dates, death-dates, and anecdotal reputation.[10] More specifically, the popular notion that the Hadith critics determined the reliability of tradents on the basis of (either personal or anecdotal knowledge of) their religious orthodoxy, piety, and general moral character is largely a back-projection of current pious Sunnī sensibilities, with little to no basis in the data that the Hadith critics themselves left behind.[11]

Secondly, again contrary to common misconception, the Hadith critics did in fact openly engage in a kind of content- or matn-based criticism: hadiths with overtly unorthodox, sectarian, or heretical content were usually rejected without further consideration, and tradents who transmitted such hadiths were automatically dismissed by some Hadith critics as unreliable or suspect.[12] (By contrast, although some hadiths were also rejected on the basis of their anachronistic or implausible content, this was usually done covertly, since it validated the approach of the hated rationalists).[13]

If a hadith was not instantly disqualified on the basis of its ideological content, the Hadith critics would attempt to ascertain the reliability of the tradents constituting its isnads: a sound (ṣaḥīḥ) hadith was one that derived via an uninterrupted chain of reliable tradents (ṯiqāt), whereas a weak (ḍaʿīf) or rejected (munkar) hadith was one that contradicted a ṣaḥīḥ hadith and/or only derived via weak or rejected tradents (ḍuʿafāʾ or munkarūn).[14] There was also a kind of grey area or middle ground between reliability and unreliability, as is reported from the early Basran Hadith critic ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdī (d. 198/814):

The people [who transmit Hadith can be divided into] three [categories].

[1] A man who has a precise memory (rajul ḥāfiẓ mutqin). For such as this, there is no disagreement about him (lā yuḵtalafu fī-hi).

[2] Another [kind of tradent is the one who sometimes] errs (yahimu), but the majority of his Hadith are sound (al-ḡālib ʿalá ḥadīṯi-hi al-ṣiḥḥah). For such as this, his Hadith are not rejected [in toto] (lā yutraku ḥadīṯu-hu); were the Hadith of the likes of this [tradent] to be rejected [in toto], [most of] the Hadith of the people would be gone (ḏahaba ḥadīṯ al-nās).

[3] Another [kind of tradent is the one who] errs (yahimu), and the majority of his Hadith are erroneous (al-ḡālib ʿalá ḥadīṯi-hi al-wahm). For such as this, his Hadith are rejected [in toto] (yutraku ḥadīṯu-hu).[15]

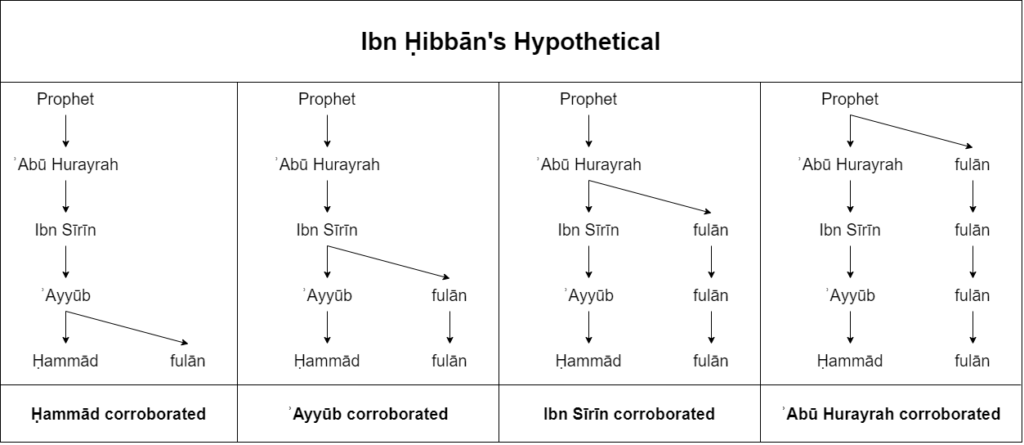

How then did a Hadith critic know whether a given tradent was reliable? Their chief method was to collate and compare the transmissions of a tradent with those of his reliable peers, to ascertain whether he was usually corroborated in his ascriptions to given sources. This process, known as “consideration” (iʿtibār),[16] is outlined by the Khurasanian Hadith critic Muḥammad b. Ḥibbān al-Bustī (d. 354/965) with the following hypothetical:

I give as an illustration of [the process called] “consideration” (l-iʿtibār) [the following, hypothetical] example, through which it will be clarified (yustadraku bi-hi) what it entails (mā warāʾa-hu).

[Suppose] that we (ka-ʾannā) come across Ḥammād b. Salamah, then we see [that] he transmitted a report from ʾAyyūb, from Ibn Sīrīn, from ʾAbū Hurayrah, from the Prophet, without our finding that report with anyone else amongst the students of ʾAyyūb. What is incumbent upon us [in a situation like this], concerning [Ḥammād], is [to] hold back from [immediately] impugning him (al-tawaqquf ʿan jarḥi-hi), and [to first] consider (al-iʿtibār) what others, from amongst his peers (min ʾaqrāni-hi), have transmitted. It is necessary that we start [by] looking at this report: did [multiple] students of Ḥammād transmit it from him, or only one man amongst them, alone? If [multiple of] his students are found to have transmitted it, then it is known that this [report] was [indeed] transmitted by Ḥammād; but if that [report] is found to be from the transmission of [only a single] weak tradent (min riwāyat ḍaʿīf) from him, then that [report] is attributed to that transmitter, not [Ḥammād].

Then, when it is confirmed that [Ḥammād] transmitted from ʾAyyūb something that he was not [directly] corroborated on (lam yutābaʿ ʿalay-hi), it is necessary to [again] pause regarding him (ʾan yutawaqqafa fī-hi), and to not [immediately] attribute weakness (al-wahan) to him. Rather, it is ascertained: did anyone other than ʾAyyūb, from amongst the reliable tradents (min al-ṯiqāt), transmit this report from Ibn Sīrīn? If that is found, then it is known that the report has a source from which it derives (la-hu ʾaṣl yarjiʿu ʾilay-hi). But, if what we described is not found, then at that point, it is ascertained: did anyone other than Ibn Sīrīn, from amongst the reliable tradents (min al-ṯiqāt), transmit this report from ʾAbū Hurayrah? If that is found, then it is known that the report has a [genuine, earlier] source (la-hu ʾaṣl). But, if what we said is not found, then it is ascertained: did anyone other than ʾAbū Hurayrah transmit this report from the Prophet? If that is found, then it is confirmed that the report has a [genuine, even earlier] source (la-hu ʾaṣl). And when [all of] that is absent, and the report itself [moreover] contradicts (yuḵālifu) the three [aforementioned] sources (al-ʾuṣūl al-ṯalāṯah) [i.e., other, established transmissions from the Prophet, or ʾAbū Hurayrah, or Ibn Sīrīn], then it is known that the report is a fabrication (mawḍūʿ), without any doubt about it (lā šakk fī-hi), and [further], that the transmitter thereof (nāqila-hu fī-hi) who was alone in transmitting it (allaḏī tafarrada bi-hi) was the one who fabricated it (waḍaʿa-hu).

This is the verdict (ḥukm) [that follows from] the consideration (al-iʿtibār) of the narrators of transmissions (bayna al-naqalah fī al-riwāyāt).[17]

Put simply, if a tradent’s transmission was corroborated by reliable co-transmitters (as verified through iʿtibār), this was evidence of reliability. (Conversely, lack of corroboration was suspect, and contradicting established transmissions was positively damning.)

A practical example of this process is attested in the following anecdote featuring the early Basran Hadith critic Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn (d. 233/848) and a fellow traditionist:

I heard Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn say: “ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʿUlayyah said to me one day: “How are my Hadith?” I said: “You are sound in Hadith (mustaqīm al-ḥadīṯ).” Then he said to me: “And how do you know that?” I said to him: “We compared (ʿāraḍnā) the hadiths of [other] people with [your hadiths], then we saw that they were sound (mustaqīmah).” Then he said, “Praise be to God!”, and he did not cease saying “Praise be to God!” and praising his Lord until he entered the house of Bišr b. Maʿrūf”—or he said: “the house of ʾAbū al-Baḵtarī”—“whilst I was with him.”[18]

The procedure was extremely straightforward: if a tradent usually transmitted hadiths from sources that other [reliable] people also transmitted the same from, then this demonstrated that he (or rarely she) was reliable. To put it simply: when A claimed to transmit from B, it would be found that [reliable] C also transmitted the same thing from B; and when A claimed to transmit from D, it would be found that [reliable] E also transmitted the same thing from D; and when A claimed to transmit from F, it would be found that [reliable] G also transmitted the same thing from F; and so on. In such a situation, A would be judged to be reliable.

Conversely, if a tradent was usually uncorroborated or even contradicted (by other, more reliable transmissions) in his transmissions from given sources, it was inferred that he was incompetent or dishonest and thus unreliable. Such was reportedly the view of the early Basran Hadith critic Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777):

ʾAḥmad b. ʿAlī al-Madāʾinī related to us: “Muḥammad b. ʿAmr b. Nāfiʿ related to us: “Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād related to us—he said: “I heard Ibn Mahdī recount of Šuʿbah [that] it was said to him: “Who is the one whose Hadith are rejected (man allaḏī yutraku ḥadīṯu-hu)?” He said: “If he transmits from well-known [tradents] that which is unknown to [other] well-known [tradents] (ʾiḏā rawá ʿan al-maʿrūfīn mā lā yaʿrifu-hu al-maʿrūfūn) and does so frequently (fa-ʾakṯara), his Hadith are rejected (ṭuriḥa ḥadīṯu-hu); and if he is excessive in error (wa-ʾiḏā kaṯura al-ḡalaṭ), his Hadith are rejected (ṭuriḥa ḥadīṯu-hu); and if he is suspected of lying (wa-ʾiḏā uttuhima bi-al-kaḏib), his Hadith are rejected (ṭuriḥa ḥadīṯu-hu); and if transmits a hadith that is agreed to be erroneous (wa-ʾiḏā rawá ḥadīṯ ḡalaṭ mujtamaʿ ʿalay-hi), yet he does not indict himself therefor (fa-lam yattahim nafsa-hu ʿinda-hu) and reject it [accordingly] (wa-taraka-hu), then his Hadith are rejected (ṭuriḥa ḥadīṯu-hu). Whatever is other than that, transmit from him (wa-mā kāna ḡayr ḏālika fa-irwi ʿan-hu).””””[19]

This criterion was reiterated by the subsequent Khurasanian Hadith critic Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj al-Naysābūrī (d. 261/875) in his Tamyīz, where he likewise appealed to lack of corroboration, or contradiction (vis-à-vis reliable tradents), as the sign of an unreliable tradent:

By means of the collection of these transmissions (bi-jamʿ hāḏihi al-riwāyāt) and comparison (muqābalah) with each other, the sound therein (ṣaḥīḥu-hā) is distinguished from the weak therein (saqīmi-hā), and the transmitters of weak reports (ruwāt ḍiʿāf al-ʾaḵbār) are distinguished from their opposites amongst the great scholars (al-ḥuffāẓ). By that [means], those knowledgeable in Hadith (ʾahl al-maʿrifah bi-al-ḥadīṯ) declared as weak (ʾaḍʿafa) ʿUmar b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾabī Ḵaṯʿam and those like him amongst the transmitters of reports—because of their transmission [of] rejected hadiths (al-ʾaḥādīṯ al-mustankarah), which are at variance (tuḵālifu) with the transmissions of the famous, reliable tradents amongst the great scholars (al-ṯiqāt al-maʿrūfīn min al-ḥuffāẓ).[20]

This is reiterated—and made clearer still—by Muslim in his Muqaddimah, where he explicitly identified the criterion for the rejection of tradents as follows:

[Concerning] anyone for whom the majority of his Hadith are rejected or erroneous (man al-ḡālib ʿalá ḥadīṯi-hi al-munkar ʾaw al-ḡalaṭ), we also abstain (ʾamsaknā) from their Hadith.

The criterion of rejection (ʿalāmat al-munkar) in the Hadith of the traditionists is [the following]: whenever his transmission of Hadith is compared (ʿuriḍat) with the transmission of those other than him amongst the approved people of memorisation (ʾahl al-ḥifẓ wa-al-riḍā), his transmission will contradict (ḵālafat) their transmission, or it will hardly ever correspond thereto (lam takad tuwāfiqu-hā). Thus, when the majority (al-ʾaḡlab) of his Hadith are like that, he is abandoned in Hadith (mahjūr al-ḥadīṯ), he is not accepted (ḡayr maqbūli-hi), and he is not used (lā mustaʿmali-hi).[21]

This principle—corroboration, or the lack thereof—is illustrated by Muslim with a hypothetical scenario comparing reliable and unreliable tradents:

Whomever you see relying upon the likes of al-Zuhrī—in terms of his fame and the quantity of his students who are perfect memorisers of his Hadith and the Hadith of others (al-ḥuffāẓ al-mutqinīn li-ḥadīṯi-hi wa-ḥadīṯ ḡayri-hi)—or the likes of Hišām b. ʿUrwah, whose Hadith are collectively spread out (mabsūṭ muštarak) amongst the scholars (ʾahl al-ʿilm), their students having transmitted from the two of them their Hadith with agreement amongst them regarding most of it (ʿalá al-ittifāq min-hum fī ʾakṯari-hi); [if this hypothetical tradent] transmits from both them, or from one of them, a number of Hadith that no one amongst their students recognises (al-ʿadad min al-ḥadīṯ mimmā lā yaʿrifu-hu ʾaḥad min ʾaṣḥābi-himā), and [if] he is [also] not from amongst those who have [otherwise] corroborated [the other students] in [transmitting] the authentic [hadiths] that they possess (wa-laysa mimman qad šāraka-hum fī al-ṣaḥīḥ mimmā ʿinda-hum), then the acceptance of the Hadith of this kind of person is not permissible.[22]

For the Hadith critics, an uncorroborated or isolated transmission (variously known by terms such as ḡarīb, tafarrud, infirād, ḵabar al-ʾâḥād, and ḵabar al-wāḥid) was only acceptable coming from a reliable tradent, i.e., a tradent who was otherwise usually corroborated, summarised as follows by the later Syrian Hadith scholar ʿUṯmān b. al-Ṣalāḥ (d. 643/1245) in his ʿUlūm al-Ḥadīṯ:

When a tradent transmits something in isolation (ʾiḏā infarada al-rāwī bi-šayʾ), it is examined. If [it is found that] what he transmitted in isolation (mā infarada bi-hi) is in conflict with something that was transmitted by someone who is better at the memorisation of such [material] and more precise (muḵālifan li-mā rawā-hu man huwa ʾawlá min-hu bi-al-ḥifẓ wa-ʾaḍbaṭ), [then] what he transmitted in isolation is an aberration [that ought to be] rejected (šāḏḏan mardūdan). [However,] if there is no conflict therewith with what others transmitted, and it is something that only he transmitted, without anyone else transmitting it, then this isolated tradent (al-rāwī al-munfarid) is examined. If he is an honest memoriser who is trusted for his exactitude and his precision (ʿadlan ḥāfiẓan mawṯūqan bi-ʾitqāni-hi wa-ḍabṭi-hi), [then] what he transmitted in isolation is accepted, and [the hadith’s] having been transmitted in isolation does not impugn it (lam yaqdaḥ al-infirād fī-hi), as [was illustrated] in the examples given above.[23] [However,] if the one who transmitted it in isolation is not one of those who are trusted for their memorisation and their precision thereon (in lam yakun mimman yūṯaqu bi-ḥifẓi-hi wa-ʾitqāni-hi li-ḏālika allaḏī infarada bi-hi), [then] his isolated transmission thereof impugns it (kāna infirādu-hu ḵāriman la-hu), ripping it from the domain of sound [Hadith] (muzaḥziḥan la-hu ʿan ḥayyiz al-ṣaḥīḥ).[24]

The reasoning here is simple: if a tradent usually transmitted hadiths that were also transmitted by his reliable peers, then it could be inferred that he was reliable in general; and if he was reliable in general, then his uncorroborated transmissions could also be accepted.

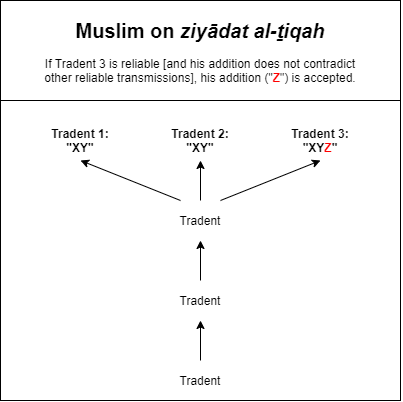

The same reasoning was applied in the case of an uncorroborated “addition” (ziyādah) within a broadly corroborated hadith, or in other words, an uncorroborated version of a hadith containing something—usually some extra element or wording—absent from parallel transmissions of the same hadith. Thus, according to Muslim:

The judgement of the scholars (ʾahl al-ʿilm)—and what we know of their method (maḏhab) regarding the acceptance of those Hadith that are transmitted by only one traditionist (mā yatafarradu bi-hi al-muḥaddiṯ min al-ḥadīṯ)—is that he should be [someone who] has [otherwise] corroborated (šāraka) the reliable tradents amongst the people of knowledge and memorisation (al-ṯiqāt min ʾahl al-ʿilm wa-al-ḥifẓ) in some of that which they transmitted (fī baʿḍ mā rawaw), and has been assiduous in agreeing with them in that (ʾamʿana fī ḏālika ʿalá al-muwāfaqah la-hum). If he is found to be like that, and he adds (zāda) thereafter something that is not [transmitted] by his companions (šayʾ laysa ʿinda ʾaṣḥābi-hi), his [uncorroborated] addition is accepted (qubilat ziyādatu-hu).[25]

To put it simply, the uncorroborated addition of a reliable tradent (ziyādat al-ṯiqah) in a hadith was acceptable to the Hadith critics, on the basis of the tradent’s having otherwise been broadly corroborated by other reliable tradents in their transmissions.

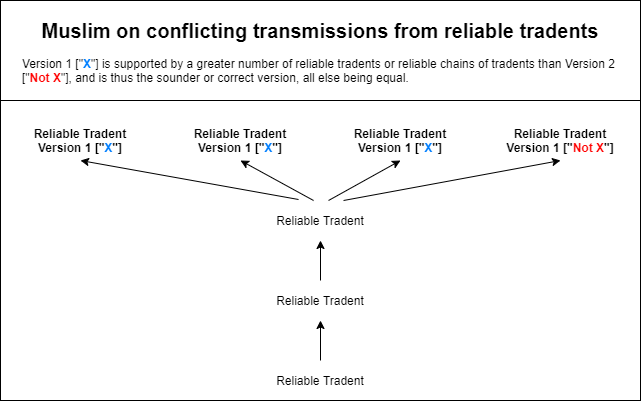

Corroboration was also the chief tool employed by Hadith critics to adjudicate between conflicting yet seemingly ṣaḥīḥ Hadith (i.e., conflicting transmissions from ṯiqāt), as Muslim again explains with a hypothetical:

[Suppose] that a group of great scholars (nafar min ḥuffāẓ al-nās) transmit a hadith from [someone] like al-Zuhrī, or some other prominent scholar (ḡayri-hi min al-ʾaʾimmah), with a single isnad and a single matn, [with all of them] agreeing upon its narration (mujtamiʿūn ʿalá riwāyati-hi) in [terms of both] the isnad and the matn, without differing thereon in meaning (lā yaḵtalifūna fī-hi fī maʿnan). Then [suppose that] someone else (ʾâḵar siwā-hum) transmits [something similar] from exactly the same person from whom the group that we described transmitted, but contradicts them (yuḵālifu-hum) in the isnad, or alters (yaqlibu) the matn, and thus makes it contradict (yajʿalu-hu bi-ḵilāf) that which was reported by those of the great scholars (al-ḥuffāẓ) whom we described. In such an instance, it is known that that the correct version (al-ṣaḥīḥ) out of the two [conflicting] transmissions is that which was related by the group of great scholars (al-jamāʿah min al-ḥuffāẓ), as opposed to the isolated one (al-wāḥid al-munfarid), even if he is [also] a great scholar (ḥāfiẓ). We have seen those knowledgeable in Hadith (ʾahl al-ʿilm bi-al-ḥadīṯ) judge Hadith according to this method (ʿalá hāḏā al-maḏhab), like Šuʿbah, Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah, Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdī, and others amongst the leading scholars (ʾaʾimmat ʾahl al-ʿilm).[26]

In other words, in the instance of a conflict between transmissions from ṯiqāt, or rival versions of a hadith transmitted by ṯiqāt, the more-corroborated transmission was usually judged to be ṣaḥīḥ, and the less-corroborated version was usually judged to be erroneous (ḵaṭaʾ, ḡalaṭ, šāḏḏ, etc.). This kind of situation may be what Ibn Mahdī had in mind when he spoke of the tradent who “errs (yahimu), but the majority of his Hadith are sound (al-ḡālib ʿalá ḥadīṯ-hi al-ṣiḥḥah).”[27]

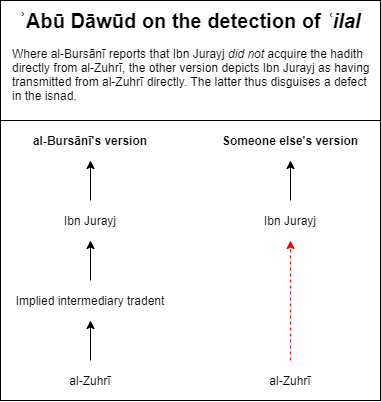

The comparison of different transmissions was also the method used by Hadith critics to identify subtle defects (ʿilal) in Hadith, as the Sijistanian Hadith critic ʾAbū Dāwūd Sulaymān b. al-ʾAšʿaṯ (d. 275/889) explained in his Risālah:

Sometimes an isnad will come along, and it will be known [by comparison] with another hadith (min ḥadīṯ ḡayri-hi) that it is not continuously transmitted (ḡayr muttaṣil). However, this would not be clear to a listener, unless he knows hadiths and has knowledge thereof: only then will he be aware of this. For example, [consider] that which is transmitted from Ibn Jurayj, who said: “It was reported to me from (ʾuḵbirtu ʿan) al-Zuhrī…” [By contrast,] al-Bursānī transmits it [as follows]: “…from Ibn Jurayj, from (ʿan) al-Zuhrī…” The one who hears [the latter] will assume that it is continuously transmitted (muttaṣil), even though it is definitely not sound (lā yaṣiḥḥu battatan). We only rejected this [version] for that [version] because the original version of the hadith (ʾaṣl al-ḥadīṯ) is not continuously transmitted (ḡayr muttaṣil) and not sound (lā yaṣiḥḥu): it is [actually] a defective hadith (ḥadīṯ maʿlūl). [Cases] like this are numerous. And [yet], an ignorant person will say: “He has rejected a sound hadith (ḥadīṯ ṣaḥīḥ) on this [matter], and has brought a defective hadith (ḥadīṯ maʿlūl) [instead].”[28]

The technique used by the Hadith critics to identify ʿilal is once again straightforward: by comparing the different isnads for a given hadith, a subtle difference can be detected. In this case, one version of the isnad seemingly displays continuous transmission (ittiṣāl), with Ibn Jurayj depicted as simply transmitting from al-Zuhrī (ʿan ibn jurayj ʿan al-zuhriyy); but the other version of the isnad indicates discontinuous transmission (ʾirsāl or inqiṭāʿ), with Ibn Jurayj stating, “it was reported to me from al-Zuhrī” (ʾuḵbirtu ʿan al-zuhriyy), rather than, for example, “al-Zuhrī reported to me” (ʾaḵbara-nī al-zuhriyy). This indicates that someone other than al-Zuhrī—some unknown or unnamed intermediary between al-Zuhrī and Ibn Jurayj—transmitted this hadith directly to Ibn Jurayj. In light of this, ʾAbū Dāwūd judged the ḡayr muttaṣil (i.e., mursal or munqaṭiʿ) version to be the original, and the muttaṣil version to be a distortion thereof.

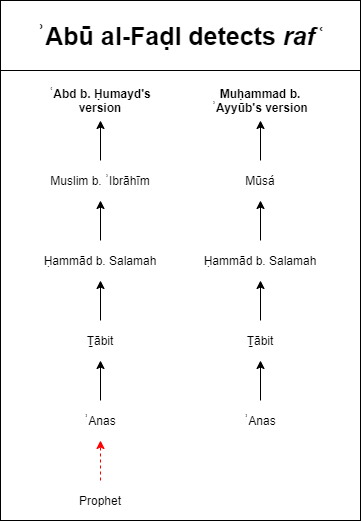

Another variety of ʿillah was “raising” (rafʿ), whereby the ascription or isnad of an existing hadith was retrojected or extended backwards from an initial source to an even earlier source—for example, when the saying of a Companion became a saying of the Prophet. Once again, it was by comparing variants that such errors or distortions were detected, as in the following example by the Khurasanian Hadith critic ʾAbū al-Faḍl Muḥammad b. ʿAmmār al-Šahīd (d. 317/929-930) in his commentary on a certain Hadith collection:

I found therein [a hadith narrated] from ʿAbd b. Ḥumayd, from Muslim b. ʾIbrāhīm, from Ḥammād b. Salamah, from Ṯābit, from ʾAnas, who said: “Whenever the Prophet would put great effort into supplicatory prayer, he would say: “May God make over you the prayer of a dutiful people; they arise at night [for prayer], and fast in the day, and they are neither sinful nor arrogant.””[29]

ʾAbū al-Faḍl said: The raising (rafʿ) of this hadith unto the Prophet is erroneous (ḵaṭaʾ), which I regard to be [the fault] of ʿAbd b. Ḥumayd.

The correct version (al-ṣaḥīḥ) is that which Muḥammad b. ʾAyyūb related to us—he said: “Mūsá related to us: “Ḥammād related to us: “Ṯābit reported to us—he said: “ʾAnas said: “Whenever one of them would put great effort into supplicatory prayer for his brother…””””” Then he recounted the hadith like [the one above].[30]

Once again, the comparison of variants was the method used to detect rafʿ.[31]

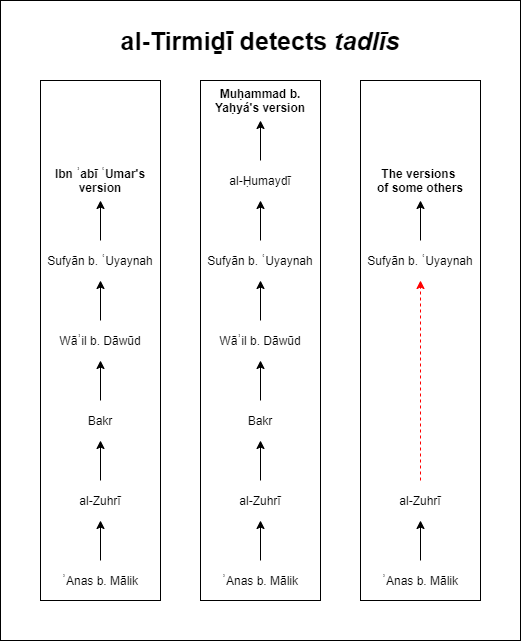

Finally, comparison also seems to have been the method by which lesser forms of deception and interpolation (tadlīs)—another variety of ʿilal—were detected.[32] For example, the Transoxanian Hadith critic Muḥammad b. ʿĪsá al-Tirmiḏī (d. 279/892) cited a hadith about the Prophet’s marriage with Ṣafiyyah in his Jāmiʿ,[33] equipped with the following isnads:

- Ibn ʾabī ʿUmar—Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah—Wāʾil b. Dāwūd—his son [i.e., Bakr]—al-Zuhrī—ʾAnas b. Mālik.

- Muḥammad b. Yaḥyá—al-Ḥumaydī—Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah—Wāʾil b. Dāwūd—his son [i.e., Bakr]—al-Zuhrī—ʾAnas b. Mālik.

Thereafter, al-Tirmiḏī commented:

Others (ḡayr wāḥid) have transmitted this hadith from Ibn ʿUyaynah, from al-Zuhrī, from ʾAnas, without mentioning therein: “from Wāʾil, from his son…” Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah has engaged in obfuscation (yudallisu) in this hadith. Sometimes he would not mention “from Wāʾil, from his son” therein, and sometimes he would mention it.[34]

By comparing the initial isnad (Sufyān—Wāʾil—his son—al-Zuhrī—ʾAnas) with this other version (Sufyān—al-Zuhrī—ʾAnas), al-Tirmiḏī easily spotted a difference.

Summary

In short, the collation and comparison of isnads seems to have been the chief tool of proto-Sunnī Hadith critics: the transmissions of given tradents were compared with those of their reliable peers to gauge whether they were usually corroborated, and thus, whether they were reliable; conflicting versions of hadiths were adjudicated on the basis of a comparison of the number of reliable transmitters of each; and errors, defects, or falsifications in hadiths were identified in the first place by the comparison of different transmissions thereof.

Through the application of this method over the course of several generations, the Hadith critics produced the Sunnī Hadith canon, numerous other Hadith collections, and a vast corpus of Hadith-related judgements and prosopography, thereby establishing the foundations of classical Sunnī Hadith scholarship.

* * *

I owe special thanks to Prof. Christopher Melchert, for providing feedback on this article; Prof. Jonathan Brown, for his feedback and for kindly providing me with access to one of his works; Terron Poole, for creating the artwork used herein; and Yet Another Student, for his generous support over on my Patreon.

[1] See especially Eerik Dickinson, The Development of Early Sunnite Ḥadīth Criticism: The Taqdima of Ibn Abī Ḥātim al-Rāzī (240/854-327/938) (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2001); Christopher Melchert, ‘Bukhārī and Early Hadith Criticism’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Volume 121, Number 1 (2001), 7-19; Scott C. Lucas, Constructive Critics, Ḥadīth Literature, and the Articulation of Sunnī Islam: The Legacy of the Generation of Ibn Saʿd, Ibn Maʿīn, and Ibn Ḥanbal (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2004); Christopher Melchert, Ahmad b. Hanbal (Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications, 2006), 48-57; Jonathan A. C. Brown, Hadith: Muhammad’s Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World, 2nd ed. (Oxford, UK: Oneworld Academic, 2018 [first published 2009]), ch. 3; Christopher Melchert, ‘The Life and Works of al-Nasāʾī’, Journal of Semitic Studies, Volume 59, Issue 2 (2014), 394-401; id., ‘Muḥammad Nāṣir al-Dīn al-Albānī and Traditional Hadith Criticism’, in Elisabeth Kendall & Ahmad Khan (eds.), Reclaiming Islamic Tradition: Modern Interpretations of the Classical Heritage (Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 37 ff.; Belal Abu-Alabbas, ‘The Principles of Hadith Criticism in the Writings of al-Shāfiʿī and Muslim’, Islamic Law and Society, Volume 24 (2017), 311-335; Christopher Melchert, ‘The Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism in the Mid-Ninth Century’, in Petra M. Sijpesteijn & Camilla Adang (eds.), Islam at 250: Studies in Memory of G.H.A. Juynboll (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2020), 74-102.

[2] In addition to the sources cited above, see Ignaz Goldziher (trans. Wolfgang Behn), The Ẓāhirīs: Their Doctrine and Their History: A Contribution to the History of Islamic Theology (Leiden, the Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1971), chs. 1-2; Joseph F. Schacht, The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1950), passim; Christopher Melchert, The Formation of the Sunni Schools of Law, 9th-10th Centuries C.E. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 1997), passim; id., ‘Traditionist-Jurisprudents and the Framing of Islamic Law’, Islamic Law and Society, Volume 8, Number 3 (2001), 383-406; id., ‘The Imāmīs between Rationalism and Traditionalism’, in Lynda Clarke (ed.), Shīʿite Heritage: Essays on Classical and Modern Traditions (Binghamton, USA: Global Publications, 2001), 273-283; Patricia Crone, Medieval Islamic Political Thought (Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), passim; Melchert, Ahmad, 59-66; Sohail Hanif, ‘Al-Ḥadīth al-Mashhūr: A Ḥanafī Reference to Kufan Practice?’, in Sohaira Z. M. Siddiqui (ed.), Locating the Sharīʿa: Legal Fluidity in Theory, History and Practice (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2019), 89-110.

[3] E.g., Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 102 ff., 107-109.

[4] E.g., ibid., 43-44.

[5] E.g., ibid., 83-84.

[6] See the misconceptions cited below, especially the notion that a tradent’s religious, pious, or moral reputation was an important factor.

[7] E.g., Melchert, Ahmad, 55; Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 69; Christopher Melchert, review of ‘Bashīr ʿAlī ʿUmar. Manhaj al-imām Aḥmad fī iʿlāl al-ḥadīth’ and ‘Abū Bakr ibn Laṭīf Kāfī. Manhaj al-imām Aḥmad fī al-taʿlīl wa-atharuhu fī al-jarḥ wa-al-taʿdīl’, Al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā, Volume 21, Numbers 1-2 (2009), 15, col. 3. In my experience, this approach also predominates in online Islamic religious and apologetical lectures and articles on the authentication of Hadith.

[8] Melchert, Ahmad, 51; Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 69; Melchert, ‘The Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism’, in Sijpesteijn & Adang (eds.), Islam at 250, 74 ff. Melchert has also suggested (via personal correspondence) that classical Sunnī Hadith scholars like Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ also incorporated concepts from the (rationalist-influenced or semi-rationalist) Sunnī legal tradition into their approach, comparing Hadith transmission to court testimony and emphasising personal character (e.g., ʿadālah).

[9] Above all, with Dickinson, Melchert, Brown, and Abu-Alabbas, cited above. For an analogue in contemporary Sunnī traditionalist scholarship, see Melchert’s above-cited review of Kāfī. Also see Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 85-86, on Ibn al-ʾAmīr al-Ṣanʿānī in the 18th Century CE, who also noticed the disconnect between proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism and later classical Hadith scholarship.

[10] Dickinson, Development, 90 ff.; Melchert, ‘Bukhārī and Early Hadith Criticism’, 11-12; id., Ahmad, 51-56; id., ‘The life and works of al-Nasāʾī’, 396; Abu-Alabbas, ‘The Principles of Hadith Criticism’, 311-312; Melchert, ‘The Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism’, in Sijpesteijn & Adang (eds.), Islam at 250, 75-76, 81.

[11] E.g., id., ‘Sectaries in the Six Books: Evidence for their Exclusion from the Sunni Community’, The Muslim World, Volume 82, Numbers 3-4 (1992), 287-295; Dickinson, Development, 90-92; Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 85-86.

[12] Dickinson, Development, 102-104; Melchert, Ahmad, 53.

[13] Jonathan A. C. Brown, ‘How We Know Early Ḥadīth Critics Did Matn Criticism and Why It’s So Hard to Find’, Islamic Law and Society, Volume 15 (2008), 143-184.

[14] All of this is elaborated in the secondary sources cited above, and some of the primary sources cited below. However, for an example, Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj al-Naysābūrī (ed. Naẓar b. Muḥammad al-Fāryābī), Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, vol. 1 (Riyadh, KSA: Dār Ṭaybah, 2006), p. 18, col. 1, states that every transmission of a hadith from a reliable tradent to another reliable tradent (kull rajul ṯiqah rawá ʿan miṯli-hi ḥadīṯan), so long as it is plausible that the two coexisted, met, and heard from each other, should be regarded as a transmission that is solidly-established (al-riwāyah ṯābitah)—so much so that it constitutes legally-binding proof (wa-al-ḥujjah bi-hā lāzimah). Muslim, ibid., p. 4, col. 2, also sets up a dichotomy between “sound transmissions” (ṣaḥīḥ al-riwāyāt) and “the reliable transmitters thereof” (ṯiqāt al-nāqilīn la-hā) on the one hand, and “weak [transmissions]” (saqīmi-hā) and “suspect tradents” (al-muttahamīn) on the other, arguing that traditionists should only transmit Hadith that are known to be “sound in origin” (ṣiḥḥat maḵāriji-hi), transmitted by those who are protected [from sin or error] (al-sitārah fī nāqilī-hi). More explicitly, ʿUṯmān b. al-Ṣalāḥ (ed. Nūr al-Dīn ʿItr), ʿUlūm al-Ḥadīṯ (Damascus, Syria: Dār al-Fikr, 1986), pp. 11-12, states that a ṣaḥīḥ hadith is one that has an isnad that—in addition to being musnad—comprises only al-ʿadl al-ḍābiṭ in terms of tradents.

It is sometimes stated in recent scholarship that, for a hadith to be ṣaḥīḥ in early Hadith criticism, it had only to be supported by multiple, independent isnads. This comes across in Dickinson, Development, 82, and Melchert, ‘The life and works of al-Nasāʾī’, 395. On the contrary, I think that multiple, independent isnads were actually not sufficient, or decisive, in the eyes of the Hadith critics. On the one hand, if a hadith was supported by only a single isnad, but one comprised entirely of ṯiqāt, it could be accepted (all else being equal), as Dickinson notes subsequently (Development, 82-83, 105-107). On the other hand, if a hadith was supported by multiple, independent isnads that all reduced at some point to tradents who were ḍaʿīf, munkar, kaḏḏāb, etc., the hadith would still be rejected, as in the spectacular example cited in Gautier H. A. Juynboll, Muslim tradition: Studies in chronology, provenance and authorship of early ḥadīth (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 207-213. Additionally, there are various cases cited by Melchert where Hadith critics rejected seemingly-corroborating isnads as the product of error or deceit: Ahmad, 54; ‘The life and works of al-Nasāʾī’, 397; ‘Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism’, in Sijpesteijn & Adang (eds.), Islam at 250, 79-81. Additionally, Muslim (ed. Fāryābī), Ṣaḥīḥ, I, p. 4, col. 2, explicitly advocated “the rejection of the Hadith transmission of the rejected tradent” (nafy riwāyat al-munkar min al-ʾaḵbār), and (ibid., p. 17, col. 1) criticised those who still use “weak hadiths and unknown isnads” (al-ʾaḥādīṯ al-ḍiʿāf wa-al-ʾasānīd al-majhūlah). Consider also the hypothetical scenario in Muḥammad b. Ḥibbān al-Bustī (ed. ʾAḥmad Muḥammad Šākir), Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān bi-Tartīb al-ʾAmīr ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn al-Fārisiyy, vol. 1 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār al-Maʿārif, 1952), pp. 117-118: whether Ḥammād falsely transmitted a hadith from ʾAyyūb, from Ibn Sīrīn, from ʾAbū Hurayrah, from the Prophet, is not determined by whether there are independent isnads therefor, per se; instead, Ibn Ḥibbān repeatedly specifies corroboration by ṯiqāt in particular. It is thus my impression that a hadith was only ṣaḥīḥ if it derived via ṯiqāt (all else being equal), regardless of whether the isnads therefor reduced to a single strand.

[15] Muḥammad b. ʿAmr al-ʿUqaylī (ed. Māzin b. Muḥammad al-Sarsāwī), Kitāb al-Ḍuʿafāʾ, vol. 1 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār Majd al-ʾIslām, 2008), p. 85, # 31.

[16] Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 84.

[17] Ibn Ḥibbān (ed. Šākir), Ṣaḥīḥ, I, pp. 117-118.

[18] ʾAḥmad b. Muḥammad b. al-Qāsim b. Muḥriz (ed. Muḥammad Muṭīʿ al-Ḥāfiẓ & Ǧazwah Badayr), Maʿrifat al-Rijāl ʿan Yaḥyá bn Maʿīn, vol. 2 (Damascus, Syria: Majmaʿ al-Luḡah al-ʿArabiyyah, 1985), p. 39, # 60.

[19] ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAdī al-Qaṭṭān (ed. Māzin b. Muḥammad al-Sarsāwī), al-Kāmil fī Ḍuʿafāʾ al-Rijāl, vol. 1 (Riyadh, KSA: Maktabat al-Rušd, n. d.), pp. 365-366, # 925.

[20] Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj al-Naysābūrī (ed. Muḥammad Muṣṭafá al-ʾAʿẓamī), Kitāb al-Tamyīz, 2nd ed. (Riyadh, KSA: Jāmiʿat al-Riyāḍ, 1982), p. 209.

[21] Id. (ed. Fāryābī), Ṣaḥīḥ, I, p. 3, col. 2.

[22] Ibid., pp. 3-4.

[23] Namely, the famous hadith of Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd al-ʾAnṣārī about intentions; the hadith of ʿAbd Allāh b. Dīnār on the sale and gifting of clientship; the hadith of Mālik b. ʾAnas about the Prophet entering Makkah wearing a certain helmet; and the ninety isolated hadiths of Ibn Šihāb al-Zuhrī.

[24] Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ (ed. ʿItr), ʿUlūm al-Ḥadīṯ, p. 79. This is admittedly a late source, but he states the principle extremely clearly, which is helpful for our purposes. The principle in question can be seen at work throughout early Hadith criticism, as variously noted or summarised in Dickinson, Development, 105-106; Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., 97-98; Abu-Alabbas, ‘The Principles of Hadith Criticism’, 325; and Melchert, ‘Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism’, in Sijpesteijn & Adang (eds.), Islam at 250, 77-78.

[25] Muslim (ed. Fāryābī), Ṣaḥīḥ, I, p. 3, col. 2.

[26] Id. (ed. ʾAʿẓamī), Tamyīz, 2nd ed., p. 172.

[27] Cited in ʿUqaylī (ed. Sarsāwī), Ḍuʿafāʾ, I, p. 85, # 31.

[28] ʾAbū Dāwūd Sulaymān b. al-ʾAšʿaṯ al-Sijistānī (ed. Muḥammad Luṭfī al-Ṣabbāḡ), Risālat ʾabī Dāwūd ʾilá ʾAhl Makkah fī Waṣf Sunani-hi (Beirut, Lebanon: al-Maktab al-ʾIslāmiyy, 1984 f.), pp. 32-33.

[29] This seems to be the Prophet praying for pious and just rulers to be installed over Muslims, who observe their prayers and such.

[30] Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad b. Muḥammad b. ʿAmmār al-Šahīd (ed. ʿAlī b. Ḥasan al-Ḥalabī), ʿIlal al-ʾAḥādīṯ fī Kitāb al-Ṣaḥīḥ li-Muslim bn al-Ḥajjāj (Riyadh, KSA: Dār al-Hijrah, 1991), pp. 130-131, # 32. The collection being commented upon is ostensibly the Ṣaḥīḥ of Muslim, as the title of Ibn ʿAmmār’s work suggests; but the extant Ṣaḥīḥ does not contain the hadith in question, as the editor of Ibn ʿAmmār’s work observes in a footnote.

[31] In general, see also Jonathan A. C. Brown, ‘Critical Rigor vs. Juridical Pragmatism: How Legal Theorists and Ḥadīth Scholars Approached the Backgrowth of Isnāds in the Genre of ʿIlal al-Ḥadīth’, Islamic Law and Society, Volume 14, Number 1 (2007), 1-41.

[32] According to Mohammad Hidayet Hosain, ‘Tadlīs’, in Martijn T. Houtsma, Arent J. Wensinck, Hamilton A. R. Gibb, Willi Heffening, & Évariste Lévi-Provençal (eds.), The Encyclopaedia of Islām: A Dictionary of the Geography, Ethnography and Biography of the Muhammadan Peoples: Supplement (Leiden, the Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1938), 222, there are three basic kinds of tadlīs: (1) tadlīs fī al-ʾisnād, i.e., (1.1) when you pretend that you heard a hadith from your source’s alleged source directly (rather than from your actual source), in the instance where the alleged source is someone from whom you otherwise transmitted Hadith; (1.2) when you deliberately delete or omit problematic tradents from the isnad of a hadith that you have received; (1.3) when you cite a false source alongside your true source for a given hadith; (1.4) when you give the false impression, through a kind of verbal trickery, that you heard a hadith directly from a false source; (1.5) when you pretend to have received a hadith from a false source, with that false source’s permission; (1.6), when you explicitly lie that you directly heard a hadith from a false source; and (1.7) when you give false impressions about the extent of your travels for Hadith; (2) tadlīs fī al-matn (more commonly known as ʾidrāj), i.e., when you deliberately add things into a matn, as if what you added also came via the isnad of the matn in question; and finally, (3) tadlīs fī al-šuyūḵ, i.e., when you deliberately refer to your sources vaguely (e.g., by a common kunyá or nisbah), so that people will mistake them for more famous people.

For an alternative schema (which divides tadlīs into only two broad categories, tadlīs al-ʾisnād and tadlīs al-šuyūḵ), see Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī, Kitāb Ṭabaqāt al-Mudallisīn (Cairo, Egypt: al-Maṭbaʿah al-Ḥusayniyyah al-Miṣriyyah, 1904), pp. 3-4.

[33] Muḥammad b. ʿĪsá al-Tirmiḏī (ed. Baššār ʿAwwad Maʿrūf), al-Jāmiʿ al-Kabīr, vol. 2 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Ḡarb al-ʾIslāmiyy, 1996), pp. 388-389, ## 1095-1096.

[34] Ibid., p. 389, # 1096.