Since the publication of Javad Hashmi’s article regarding my DPhil research, some readers have quite understandably asked for more details. The full DPhil thesis should be available soon (and will be made available on this blog), but in the meantime, I can at least offer a summary thereof to give a better idea of the relevant methodologies, argumentation, and evidence used therein. (An alternative summary, in the form of a lecture, is available on The Impactful Scholar, here.)

INTRODUCTION

To begin with, I surveyed some of the notable comments on the authenticity of this hadith in the past, including those of Muḥammad Nāṣir al-Dīn al-ʾAlbānī, Gautier Juynboll, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-ʾIdlibī, Jonathan Brown, and Yasmin Amin, variously noting my agreement or disagreement with their methods and conclusions.

CHAPTER 1: METHODS & DEBATES

Next, I noted the various reasons for general skepticism towards Hadith, before surveying most of the major dating methods that have been put forward in Hadith Studies over the last century, including:

- Joseph Schacht’s relative dating based on Hadith ascription-types, which I defend based on the chronology of the citation of Hadith and different Hadith types across the earliest works, in conjunction with the Criterion of Dissimilarity.

- Schacht’s arguments from silence, which I defend within specific parameters (intra-regional failures to cite expedient hadiths from major authorities), whilst acknowledging the circumstances in which it is invalid (failures to cite inexpedient hadiths, and inter-regional failures to cite expedient hadiths, at least early on).

- Harald Motzki’s tradition-historical source analysis, which I reject as unsound (i.e., as relying on a false dichotomy, ignoring more dynamic models of false creation, disregarding early rapid mutation, etc.), following the criticisms of Gerald Hawting, Christopher Melchert, and Paul Gledhill.

- The “common link” method (or family of methods), tracing the whole dialectic from Schacht to Motzki and noting all of the different interpretations and criticisms (along with the strengths and weaknesses of both), culminating in a defence of a critical and consistent version of the isnad-cum-matn analysis.

Additionally, I summarised the different views on the role of the common link or CL (fabricator vs. transmitter), before noting the consensus that the CL was at minimum the paraphrastic formulator of the extant, underlying ur-form of their hadith, and further adducing the established chronology of Hadith transmission to justify caution regarding the accuracy of pre-CL “single strand” or SS isnads.

CHAPTER 2: AN ISNAD-CUM-MATN ANALYSIS

Next, I used various anthologies and databases—including Arent Wensinck’s A Handbook of Early Muhammadan Tradition, Gautier Juynboll’s Encyclopedia of Canonical Ḥadīth, Yūsuf b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mizzī’s Tuḥfat al-ʾAšrāf bi-Maʿrifat al-ʾAṭrāf, Baššār Maʿrūf et al.’s al-Musnad al-Jāmiʿ, Islamweb, and Shamela—to locate all extant versions of the hadith, using every combination of every relevant element and key wording to find even the more obscure ones. I found thereby some 200+ versions, all of which I collated, translated, and transliterated, thus creating my own dedicated anthology for this hadith. Additionally, I created my own biographical dictionary of all of the tradents cited in all of the isnads for this hadith, synthesising their basic information from various works of Hadith-related prosopography: when they were born and died; where they lived; from whom, and to whom, they transmitted; and what other scholars said about them.

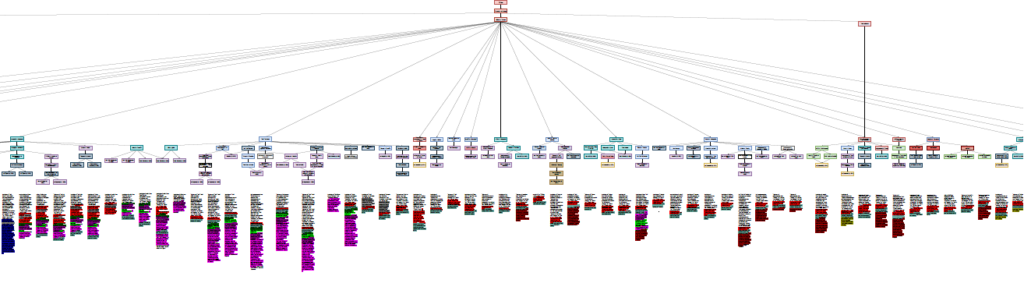

Thereafter, I created a new kind of Hadith diagram, placing therein not just all of the isnads of the hadith, but also all of the matns. The tradents comprising the isnads (each hyperlinked to an entry on them in an online biographical dictionary) were assigned colours, to make their geographical provenance clear at a glance; and the elements constituting the matns were likewise assigned colours, to make their levels of relatedness—or dissimilarity—clear from a glance.

Thereafter, it was a simple task (though certainly an extremely time-consuming one) to implement an isnad-cum-matn analysis, which can be undertaken two ways. Firstly, you can look at the matns and arrange them into textual clusters—families and sub-families—based on the level of similarity or dissimilarity in their elements and wordings; then, you can cross-reference these findings with the isnads of the relevant versions, to see whether these textual families and subfamilies line up with the citation of “common links” and “partial common links”. Or, alternatively: first, you can cluster the versions according to the “partial common links” and “common links” cited in their isnads; then, by comparing the matns of the resulting clusters, you can see whether they are internally more alike—lining up with their putative common sources—or not. The ICMA posits that the correlation between particular elements or wordings and particular cited sources—vis-a-vis others—is generally explained by the relevant versions’ having more or less accurately preserved something of the common source’s original redaction, which now underlies the extant transmissions therefrom. (Conversely, when the matns ascribed to a common source are disparate or more similar to those ascribed to other figures than to each other, this is consistent with the occurrence of contamination, borrowing, and false ascription.)

By systematically and consistently applying this method to the marital-age hadith, distinctive traditions could be correlated with the following CLs, whose underlying redactions were thus reconstructable:

ʾIsḥāq b. Rāhwayh (d. 238/853) [Khurasanian]

Yaḥyá b. ʾÂdam [Kufan]—al-Ḥasan b. Ḥayy [Kufan]:

He saw a twenty-one-year-old grandmother; the minimum age of pregnancy is nine; ʿĀʾišah’s marriage was consummated at nine.

al-Ḥajjāj b. ʾabī Manīʿ (d. post-216/831) [Levantine]

ʿUbayd Allāh b. ʾabī Ziyād [Levantine]—Ibn Šihāb al-Zuhrī [Madino-Levantine]:

Married ʿĀʾišah; after Ḵadījah; shown in a dream; married in Makkah at six; consummation; Hijrah; nine; ʿĀʾišah’s genealogy; virgin; ʾAbū Bakr’s name.

al-Wāqidī (d. 207/823) [Madinan]

ʿAbd al-Wāḥid b. Maymūn [Madinan]—Ḥabīb [Madinan]:

Ḵadījah’s death; ʿĀʾišah shown by angel; Prophet’s interactions with ʿĀʾišah’s family; ʿĀʾišah’s birth; ʿĀʾišah’s marriage at six; marriage to Sawdah.

Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan (d. turn of 9th C. CE) [Kufan]

Sufyān al-Ṯawrī [Kufan]—Saʿd b. ʾIbrāhīm [Madinan]—al-Qāsim b. Muḥammad [Madinan]—ʿĀʾišah [Madinan]:

Marriage at six; consummation at nine; consummation in Šawwāl; [she was the preferred wife; she preferred women to be consummated in Šawwāl].

ʿAbṯar b. al-Qāsim (d. 178/794-795) [Kufan]

Muṭarrif [Kufan]—ʾAbū ʾIsḥāq [Kufan]—ʾAbū ʿUbaydah [Kufan]—ʿĀʾišah [Madinan]:

Marriage at nine; together nine years.

ʾAbū ʿAwānah al-Waḍḍāḥ (d. 176/792) [Wasitian-Basran]

ʿAbd al-Malik b. ʿUmayr [Kufan]—ʿĀʾišah [Madinan]:

Special attributes; marriage at six/seven; angel brought image; consummation at nine; seeing Gabriel; most-beloved; illness; angels.

ʾIsrāʾīl b. Yūnus (d. 160-162/776-779) [Kufan]

ʾAbū ʾIsḥāq [Kufan]—ʾAbū ʿUbaydah [Kufan]:

ʿĀʾišah was married at six; consummation at nine; Prophet died when she was eighteen.

Sulaymān al-ʾAʿmaš (d. 147-148/764-766) [Kufan]

ʾIbrāhīm [Kufan]—al-ʾAswad [Kufan]—ʿĀʾišah [Madinan]:

Marriage at nine; [[together nine years]/[Prophet died when she was eighteen]].

[That said, al-ʾAʿmaš’s CL status is quite tenuous, being based on the transmission of the mudallis ʾAbū Muʿāwiyah and two parallel, secondary-looking SSs, one of which was likely borrowed from the other.]

Hišām b. ʿUrwah (d. 146-147/763-765) [Madinan]

ʿUrwah [Madinan]:

ʿĀʾišah was married at six or seven; consummation at nine.

Hišām b. ʿUrwah (d. 146-147/763-765) [Madinan]

ʿUrwah [Madinan]:

ʿĀʾišah was married at six or seven; consummation at nine.

Anonymous:

The Prophet died when she was eighteen.

Hišām b. ʿUrwah (d. 146-147/763-765) [Madinan]

ʿUrwah [Madinan]:

ʿUrwah wrote to [al-Walīd b.] ʿAbd al-Malik; [Ḵadījah’s death;] ʿĀʾišah’s marriage, after Ḵadījah’s death; dream-vision of ʿĀʾišah; marriage at six; consummation, after the Hijrah, at nine; [ʿĀʾišah’s death].

Hišām b. ʿUrwah (d. 146-147/763-765) [Madinan]

ʿUrwah [Madinan]—ʿĀʾišah:

Marriage at six; Hijrah; illness, hair; swing; marital preparation; consummation at nine.

ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʾabī Ḵālid (d. 146/763-764) [Kufan]

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī al-Ḍaḥḥāk [unknown]—ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Muḥammad [unknown]:

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ṣafwān and someone else came to ʿĀʾišah, who mentioned her nine special attributes; angel brought image; marriage at seven; consummation at nine; virgin; revelation in blanket; most-beloved; Quranic revelation and communal destruction; seeing Gabriel; the Prophet’s death and the angel.

Muḥammad b. ʿAmr (d. 144-145/761-763) [Madinan]

Yaḥyá [Madinan] & ʾAbū Salamah [Madinan]:

Ḵawlah convinces the Prophet to propose to ʿĀʾišah and Sawdah; Ḵawlah brings word to ʾUmm Rūmān and waits for ʾAbū Bakr; ʾAbū Bakr questions the validity of the proposal, but the Prophet assuages him; ʾUmm Rūmān informs Ḵawlah of a prior engagement with al-Muṭʿim’s son; ʾAbū Bakr visits al-Muṭʿim and his wife, who call off the engagement on religious grounds, to ʾAbū Bakr’s relief; ʾAbū Bakr sends for the Prophet and engages ʿĀʾišah to him; she is age six; Ḵawlah then goes to Sawdah, and passes on the proposal to her venerable father, who approves the match; Sawdah’s father sends for the Prophet and engages her to him; Sawdah’s brother disapproves, but later regrets having done so.

—ʿĀʾišah [Madinan]:

Hijrah; women; swing; shoulder-length hair; marital preparation; marital consummation; Saʿd brings food; nine.

By contrast, the transmissions from the following key figures turned out to be disparate, which is consistent with their being the target of successive but uncoordinated false ascriptions derived from other sources:

- The ascriptions to Šarīk b. ʿAbd Allāh (d. 177-178/793-795) fundamentally contradict each other and look like they were borrowed from the versions of the CL ʾIsrāʾīl and the PCLs Jarīr or Ḥammād b. Zayd (from the CL Hišām).

- The ascriptions to ʾAbū ʾIsḥāq al-Sabīʿī (d. 127-128/744-746) fundamentally contradict each other and look like they were borrowed from various iterations of the traditions of the CLs al-ʾAʿmaš and Hišām.

- The ascriptions to Ibn Šihāb al-Zuhrī (d. 124/741-742) are highly discrepant and look like they were borrowed from the versions of the PCL ʾAbū Muʿāwiyah and the CL ʾIsrāʾīl, and although a genuine biographical report about ʿĀʾišah can be plausibly traced back to al-Zuhrī, it lacked the marital-age elements (which were added thereto by the notorious al-Wāqidī).

- The ascriptions to ʾAbū Salamah (d. 94/712-713 or 104/722-723) fundamentally contradict each other and look like they were borrowed from two different traditions disseminated by Hišām: a simple version (especially that of the PCL Wuhayb), which was taken and given a new Egypto-Madinan SS; and an elaborate version, which was taken by the CL Muḥammad b. ʿAmr, combined with several other discrete reports, and given a new Madinan SS.

- The ascriptions to Jābir b. Zayd (d. 93/711-712 or 103/721-722), although at first glance feasible (i.e., seeming quite alike), contradict each other on a basic detail, are suspiciously elaborate and prosopographical, and look like they were cobbled together from several different sources, including the tradition of the CL ʾIsrāʾīl.

- The ascriptions to ʿUrwah b. al-Zubayr (d. 93-95/711-714 or 101/719-720) are highly disparate, with one being borrowed from the PCL Sufyān al-Ṯawrī (within the broader tradition from the CL Hišām), another being an interpolation of the version of the PCL Ibn ʾabī al-Zinād (from the CL Hišām), and another (from the PCL Maʿmar) seemingly being the product of raising and likely deriving from the CL Hišām in any case. All of this leaves only Hišām’s uncorroborated transmissions from his father, which Hišām at minimum substantially altered and updated in successive retellings.

- The ascriptions to al-ʾAswad b. Yazīd (d. 75/694-695) fundamentally contradict each other, with one being an interpolated version of the famous ʾifk hadith, and the other being completely uncorroborated.

- The ascriptions to ʿĀʾišah bt. ʾabī Bakr (d. 57-58/677-678) fundamentally contradict each other, and most are demonstrably the product of raisings and interpolations.

Similar considerations apply to all of the remaining isolated SS ascriptions to other figures (such as Qatādah b. Diʿāmah, Ḥabīb al-ʾAʿwar, and ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbbās), which are either blatantly borrowed straight from the traditions mentioned above, or else look like elaborate secondary constructions. Other uncorroborated ascriptions, such as those to ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad b. ʿUqayl and ʾIsmāʿīl b. Jaʿfar, are dubious on other grounds (such as lacking an isnad or being recorded in suspect polemical circumstances).

The result of all of this was clear: this hadith cannot he traced back any earlier than the CLs ʾIsrāʾīl b. Yūnus (d. 160-162/776-779), Sulaymān al-ʾAʿmaš (d. 147-148/764-766), Hišām b. ʿUrwah (d. 146-147/763-765), ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʾabī Ḵālid (d. 146/763-764), and Muḥammad b. ʿAmr (d. 144-145/761-763). Certainly, it cannot be traced back to ʾAbū ʾIsḥāq, al-Zuhrī, or ʿUrwah, let alone ʿĀʾišah—at least on the basis of an ICMA.

CHAPTER 3: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS

Next, I subjected these reconstructed CL redactions to a further set of form-critical, geographical, and historical-critical analyses, yielding a deeper set of conclusions.

Form Criticism

By comparing the underlying forms and structures of the CL redactions and all remaining versions, it became clear that a common formula prevails therein, with all exceptions thereto invariably being secondary reformulations (e.g., PCL or sub-PCL redactions). Thus, despite their disparate cited sources, all versions of the marital-age hadith appear to derive from a common narrative origin, a single ur-hadith, rather than from independent memories or descriptions of a common event. Given the diverse isnads and ascriptions for this hadith, this indicates that a common source has been disguised or suppressed, whether deliberately or inadvertently. The only question is: who was this ultimate source? Was it ʿĀʾišah herself, or someone later—say, her nephew ʿUrwah, or his son Hišām?

Through the application of the standard textual-critical principle of utrum in alterum abiturum erat (“which would have been more likely to give rise to the other?”), it transpires that the redaction of Hišām—who towers above his contemporaries as a veritable super-CL for this hadith—is either closest to reflecting, or else simply is, the ur-hadith in question. In other words, his original, vague formulation of “married at six or seven and consummated at nine”, uniquely amongst all versions, can explain the rise of all the other versions (bar the super-rare and late “ten”), through standard mechanisms like specification, conflation, scribal error, etc. Thus, “married at six or seven and consummated at nine” (Hišām originally) variously became: “married at six and consummated at nine” (Hišām at times, and then Muḥammad b. ʿAmr, ʾIsrāʾīl, Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan, al-Ḥajjāj b. ʾabī Manīʿ, et al.); “married at seven and consummated at nine” (Hišām at times, and then ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʾabī Ḵālid); “married at nine or seven” (Maʿmar according to Ibn Saʿd); and “married at nine” (al-ʾAʿmaš and then ʿAbṯar).

Geography and Arguments from Silence: The Evidence of the Isnads

An analysis of the geographical provenance of the earliest CLs for the marital-age hadith reveals a striking fact: all of them were Iraqi (overwhelmingly Kufan) or, in two cases (Muḥammad b. ʿAmr and Hišām), Madinans who moved to Iraq and transmitted the hadith to dozens of Iraqi students. This overwhelmingly Iraqi (especially Kufan) association already immediately suggests that the hadith’s origins lie in that region.

However, there are four ostensible exceptions in the case of Hišām—four students to whom he seemingly transmitted the hadith whilst he was still in Madinah: Maʿmar b. Rāšid (d. 152-154/769-771), an itinerant Basran who met Hišām in Madinah; ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī al-Zinād (d. 164/780-781 or 174/790-791), a Madinan; Saʿīd b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (d. 172/788-789 or 194-196/809-812), another Madinan; and ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad b. Yaḥyá b. ʿUrwah (fl. turn of 9th C. CE), yet another Madinan. As it happens, however, all of these transmissions are dubious or equivocal:

- The transmission from ʿAbd Allāh is completely isolated, and the matn contains some unusually-specific details, all of which makes it look like a dive (i.e., a false, secondary isnad) supporting an updated matn. (As it happens, the isnad also contains ḍaʿīf and matrūk/munkar tradents.)

- Saʿīd was a Madinan who just so happens to have moved to Iraq; the transmission from him is completely isolated; and his having heard from Hišām (whether in Madinah or Iraq) is chronologically impossible, given that Hišām reportedly died (146-147/763-765) before Saʿīd was born (157/773-774).

- Maʿmar can only be positively attributed, via an ICMA, based on the parallel transmissions of ʿAbd al-Razzāq (who substantially interpolated his version with extraneous elements and also altered the isnad) and especially Ibn Saʿd (whose transmission is to be privileged based on the Criterion of Dissimilarity), the following, somewhat garbled version of the hadith: “Al-Zuhrī and Hišām b. ʿUrwah said: The Prophet married ʿĀʾišah when she was a girl of nine years or seven.” This version is uncorroborated by all other transmissions from Hišām, which is consistent with his having obtained it indirectly (in defective writing and/or via an intermediary). The certainty of Maʿmar’s having directly heard the hadith from Hišām (which would entail a Madinan locale) is thus removed.

- Matters are less straightforward with Ibn ʾabī al-Zinād, for whom there are two pieces of evidence reinforcing his receiving of the hadith from Hišām in Madinah. Firstly, he transmitted the hadith to al-Wāqidī, who remained in Madinah for as long as Ibn ʾabī al-Zinād lived—thus, if he received the hadith directly from Ibn ʾabī al-Zinād, this can only have occurred in Madinah. Secondly, there is a report that places Ibn ʾabī al-Zinād in Madinah as late as 760-762 CE, very shortly before Hišām’s death in Iraq—this leaves only a tiny window of time for any kind of extra-Madinan transmission to occur between these two tradents. However, it just so happens that al-Wāqidī moved to Iraq, and that he was famously a fabricator, and that he demonstrably interpolated or falsely ascribed all other versions of this very hadith that he transmitted. Moreover, it just so happens that Ibn ʾabī al-Zinād also moved to Iraq, and that he is never actually quoted as saying “Hišām reported to me” (i.e., he is not actually depicted as claiming direct transmission), and that he was remembered as having become unreliable specifically after he moved to Iraq. The situation is thus ideal for some minor false ascription to have occurred.

We are thus left with an unbearable coincidence: virtually all signs point to Iraq, and the only four alleged exceptions just so happen to be (1) a SS ascription to a Madino-Baghdadian tradent—appearing in an isolated variant within the transmissions of another tradent—who was reportedly born after Hišām died; (2) a SS ascription of a markedly divergent—unusually-detailed and secondary-looking—matn to a Madinan tradent that looks like a dive; (3) a fundamentally divergent and uncorroborated transmission from the itinerant Basran tradent Maʿmar b. Rāšid (who met Hišām in Madinah but may have returned home several times), which is consistent with being a garbled, indirect transmission from Hišām; and (4) the transmission of the Madinan PCL ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī al-Zinād, who just so happens to have moved to Baghdad (where he became unreliable). This is exactly what it would look like if Hišām only disseminated the marital-age hadith in Iraq, and if the—inevitable or predictable—secondary process of tadlīs and spreading isnads generated a few stray instances of pseudo-Madinan ascription (i.e., the superficial appearance of Madinan transmission).

Geography and Arguments from Silence: The Earliest Madinan Collections

All of the above is strikingly confirmed by the total absence of the marital-age hadith from any early Madinan legal or biographical work, or any early dedicated collection of Madinan material, including Mūsá b. ʿUqbah’s Maḡāzī (as far as we can tell), Ibn ʾIsḥāq’s Maḡāzī, Mālik’s Muwaṭṭaʾ, Saḥnūn’s Mudawwanah, and all other early Mālikī works. If indeed the hadith was already being disseminated in Madinah by such notables as Ibn ʾabī al-Zinād, Hišām, Muḥammad b. ʿAmr, Ibn Šihāb al-Zuhrī, ʿUrwah, ʾAbū Salamah, and ʿĀʾišah, it is reasonable to expect that it would be cited in at least some of these works (if not all of them), especially given its utility for both legal matters (as a useful prooftext on the marriage of virgins and prepubescent girls, which was much debated) and the biography of the Prophet (as a detail in his life and his marriage to his favourite wife). Indeed, most of these works collected material on, or had sections devoted to, the topics addressed by this hadith, including the marriage of virgins, the marriage of prepubescent girls, and the Prophet’s marriages to his wives. The consistent, collective Madinan silence thereon is thus completely unexpected on the view that it was circulating there, which is to say, strong evidence pointing to its early absence in Madinah. This strengthens the hadith’s Iraqi origin, by rendering unlikely the pre-Iraqi Madinan origin claimed by Hišām et al.

Geography and Arguments from Silence: The Earliest Kufan Collections

The Iraqi CLs who cited Madinan sources evidently did so falsely, but what of those who cited local (Kufan) sources? ʿAbṯar’s version (based on an ICMA) was straightforwardly borrowed from the tradition of al-ʾAʿmaš and can be discarded accordingly, and ʾAbū ʿAwānah and ʾIsmāʿīl’s hadiths are clearly reworkings of a common pool of 8th-Century proto-Sunnī Kufan faḍāʾil material, earlier versions of which completely lack the marital-age elements (which were evidently borrowed from Hišām’s tradition). This leaves us with ʾIsrāʾīl (from ʾAbū ʾIsḥāq, from ʾAbū ʿUbaydah), and al-ʾAʿmaš (from ʾIbrāhīm al-Naḵaʿī, from al-ʾAswad, from ʿĀʾišah). Both of these ascriptions are in turn rendered highly suspect by the absence of either from any proto-Ḥanafī (i.e., Kufan regionalist or rationalist) legal collection. The Kufan legal tradition was obsessed with—and transmitted hundreds upon hundreds of reports from—none other than both ʾIbrāhīm and the ʾaṣḥāb of Ibn Masʿūd, and ʾAbū ʿUbaydah was latter’s son. Thus, if indeed ʾIbrāhīm and ʾAbū ʿUbaydah had transmitted what is attributed to them, it is reasonable to expect that their respective reports would be cited by the proto-Ḥanafīs. But of course, they are not, which is consistent with both reports’ having originated amongst the later traditionists of Kufah, rather than in the more archaic Kufan legal tradition that was inherited by the proto-Ḥanafī jurists.

[Of course, the extant ʾAṣl ascribed to al-Šaybānī (d. 189/804-805) cites the marital-age hadith, and al-Saraḵsī ascribes its citation back to Ibn Muqātil (d. 248/862-863) as well. However, there are strong reasons to regard the former as an interpolation or later reworking, and the latter as an error, noted here. Moreover, the wording allegedly cited by al-Šaybānī is not that attributed to ʾIbrāhīm and the ʾaṣḥāb of Ibn Masʿūd, so an unexpected silence remains regardless.]

Interim Conclusion

When all of these results are combined, the conclusion is inescapable: all extant versions of the marital-age hadith trace back to Hišām after he moved to Iraq. To recapitulate: it cannot be traced back to Madinah in the 7th or 8th Centuries CE; it cannot he traced back any earlier than Hišām and his contemporaries in Iraq (i.e., does not go back to the preceding Iraqi generations); all versions derive from an ur-version; Hišām’s version was the most widespread of all; and Hišām’s version uniquely looks like the ur-version behind all the rest. What actually explains all of this, and what is certainly the simplest explanation therefor, is that Hišām created this hadith.

Historical-Critical Analysis

As it happens, this conclusion fits perfectly with Hišām’s specific conditions and context, or in other words: Hišām in particular had both a strong motive and a reputation for certain forms of false ascription. In the first case, an ideological battle was raging between proto-Sunnīs and proto-Šīʿīs over ʿĀʾišah, who was loved by the former and despised by the latter—thus, the proliferation (i.e., fabrication) of pro-ʿĀʾišah hadiths amongst defensive proto-Sunnī sectaries, above all in the 8th-Century Šīʿī stronghold of Kufah. One of ʿĀʾišah’s stock virtues (faḍāʾil) in these proto-Sunnī polemics and apologetics was her status as the Prophet’s only virgin wife, which helped to justify the proto-Sunnī claim that she was also his favourite wife. And, as it happens, Hišām, a proto-Sunnī and a kinsman to ʿĀʾišah, only seems to have created this hadith after he moved to—or extremely close to—Šīʿī-dominated Kufah, where it was immediately incorporated into local faḍāʾil reports about ʿĀʾišah (by ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʾabī Ḵālid and ʾAbū ʿAwānah), evidently because it bolstered or highlighted her virginity, as Denise Spellberg observed. All of this creates a strong motive for Hišām to have created this hadith: in response to his new sectarian environment, to defend his great-aunt ʿĀʾišah.

Moreover, as it happens, Hišām was widely remembered as having become unreliable specifically after he moved to Iraq, and was even accused by later scholars (such as Ibn Ḵirāš, Ibn Šaybah, and Ibn Ḥajar) of having falsely ascribed hadiths to his father. Once again, everything lines up: all of this is consistent with Hišām’s having created the marital-age hadith—a false ascription to his father—after he moved to Iraq.

Summary

In short: a geographical analysis of the isnads of the marital-age hadith reveals an overwhelming Iraqi—especially Kufan—association with all the earliest CLs, with the handful of apparent exceptions (tying Hišām to Madinah) all being equivocal or suspect; the absence of the hadith from any early Madinan work precludes its circulation in early Madinah (by Hišām or anyone else); the absence of the hadith from any proto-Ḥanafī work precludes its circulation amongst the earlier notables of Iraq (i.e., before Hišām and his fellow CLs); form criticism indicates that all versions of the marital-age hadith derive from a single ur-hadith, and that Hišām’s version uniquely fits as such; and a historical-critical analysis reveals that Hišām in particular had both a strong motive to falsely create this hadith and a reputation for certain forms of false ascription specifically when he moved to Iraq. Everything converges on a single point: Hišām, the super-CL whose transmissions dwarf all the rest, created the marital-age hadith.

CHAPTER 4: SPREAD AND DIVERSIFICATION

Next, I re-summarised the results of my ICMA and further critical analyses, but this time, arranged according to geography and chronology, thereby giving a coherent overview of the origins, spread, and diversification of the marital-age hadith. In doing so, I accounted for the appearance of all extant versions of the hadith. Additionally, I noted that new versions with false ascriptions that arose across the different provinces of the Abbasid Caliphate were usually transmitted by tradents with mixed or negative reputations.

CHAPTER 5: CANONISATION

Next, I documented the reception of this hadith by proto-Sunnī Hadith critics from the 9th Century CE onward, who criticised some versions, but did so sporadically, and largely seem to have accepted the hadith—or rather, inherited it from their venerated predecessors—without comment or question.

CHAPTER 6: BROADER IMPLICATIONS

Finally, I outlined the various implications of my findings, for both the methods and debates of Hadith Studies, on the one hand, and early Islamic history, on the other. For an example of the first, the results of my ICMA broadly corroborate Schoeler and Yanagihashi’s chronology of the development of Hadith transmission. For an example of the second, it follows from my ultimate conclusion that we no longer have any solid basis for thinking that Muḥammad married ʿĀʾišah as a child. That said, I argue that such a conclusion can be reached independently of all of my research, simply on the basis of established background knowledge on the general absence of accurate record-keeping regarding chronology, dates, and ages in rural, oral, and stateless societies. In other words, even if the hadith truly derived from ʿĀʾišah herself, there would be reason to doubt it: the information contained therein is likely not the kind that ʿĀʾišah would have—or even could have—known or retained in the stateless and rural environment of early 7th-Century Hijaz.

***

All of this gives at least a sense of the argumentation and evidence in my thesis, but as for the details and references, those will have to await its release. When my thesis becomes available (which should happen soon), I will upload a copy here, on my blog.

***

I owe thanks to Mehrab, abcshake, Marijn van Putten, and especially Yet Another Student, for their generous support over on my Patreon.