The hypothesis that early Islam—from the time of the Prophet to at least the second fitnah—constituted some kind of pan-Abrahamic or pan-Abrahamitic movement or coalition is widespread in recent secular, critical scholarship.[1] The earliest iteration of this hypothesis—which posited that proto-Islam was some kind of Judaeo-Arab alliance or coalition—can be found in Patricia Crone and Michael Cook’s 1977 monograph Hagarism,[2] along with Cook’s 1983 monograph Muhammad[3] and Crone’s 1987 monograph Meccan Trade.[4] Thereafter, a revised version of this hypothesis—which posited that proto-Islam was an ecumenical or confessionally-open “Community of Believers” containing Muslims, Jews, and Christians—appeared in Fred Donner’s 2002-2003 article “From Believers to Muslims”[5] and in his 2010 monograph Muhammad and the Believers.[6] Donner’s version has gone on to win widespread acceptance amongst scholars of early Islamic history, including Reuven Firestone, Stephen Shoemaker, Robert Hoyland, Juan Cole, and others.[7] Of course, there remain notable scholars who criticise and reject this hypothesis, including Sean Anthony,[8] Nicolai Sinai,[9] Jonathan Brockopp,[10] and Jack Tannous.[11] Even Crone, an advocate of her own version of the pan-Abrahamitic thesis, criticised Donner’s.[12] Still, Donner’s version of the thesis retains strong scholarly support (such that its status as a mainstream idea cannot be credibly denied), and even Brockopp and Tannous concede that early Islam’s confessional borders were fuzzy and fluid at best.[13] Thus, according to Michael Penn:

What was once relegated to a handful of specialists has become increasingly mainstream in the study of classical Islam. Recent works by scholars such as Chase Robinson, Stephen Shoemaker, and others emphasize the difficulties in differentiating seventh-century Islam from other monotheistic traditions. Although not without its detractors, such scholarship suggests a fairly substantial paradigm shift.[14]

The adherents of the pan-Abrahamitic thesis—especially Crone, Donner, and Shoemaker—have variously pointed to the following points of evidence in their scholarship:

- (1) The Quran, which (1a) overwhelmingly addresses “Believers” (muʾminūn) rather than “Muslims” (muslimūn), (1b) seemingly distinguishes between the two (with the reviled bedouins being identified as the latter rather than the former), (1c) seemingly recognises some People of the Book as members of its movement, and (1d) seemingly recognises the salvation of some of the People of the Book.[15]

- (2) The Ṣaḥīfat Yaṯrib (better known as “the Constitution of Madinah”), which depicts Jews as members of Muḥammad’s politico-religious community (ʾummah), alongside Believers and Muslims.[16]

- (3) Early non-Muslim literary sources, which variously depict (3a) an alliance between the Arabs and the Jews that lasted until after the great conquests,[17] (3b) an early Jewish recognition of Muḥammad as a messianic figure,[18] (3c) a substantial Christian presence in the early Arab armies,[19] (3d) early Muslims praying in Christian holy spaces,[20] and (3e) an early Muslim acceptance of the Torah.[21]

- (4) Early Arabic or proto-Islamic media (coins, papyri, and inscriptions), which (4a) consistently refer to the proto-Islamic movement and its members as “Believers” (muʾminūn) rather than “Muslims” (muslimūn) up until the Marwanid period,[22] and (4b) consistently proclaim a generic monotheistic creed (e.g., the Basmalah and the single Šahādah) rather than anything distinctively, specifically, or exclusively Islamic (e.g., the double Šahādah).[23]

- (5) Dissonant Islamic reports (preserved in the extant Hadith corpus), which variously depict (5a) an early Muslim reliance on the Torah,[24] (5b) early Muslims praying in and constructing Christian churches,[25] and (5c) a strong Christian presence in the military and the government.[26]

(To these we can add an early Christian Arabic graffito that was recently discovered in Jordan, which invokes God’s blessings upon the Umayyad ruler Yazīd I and thus “may suggest that Christians, or at least Christian Arabs, would have viewed the caliph as their own.”)

Some of this evidence is certainly equivocal or could be interpreted in multiple ways, but it seems hard to deny that the simplest explanation for all of this evidence together is that proto-Islam was in some way a pan-Abrahamitic movement or coalition. Certainly, the pan-Abrahamitic thesis cannot be dismissed flippantly.

This brings us to a recent development. In the aftermath of a debate on this topic a few days ago (here), an interesting piece of conflicting evidence against Donner’s version of the pan-Abrahamitic thesis was adduced on Twitter:

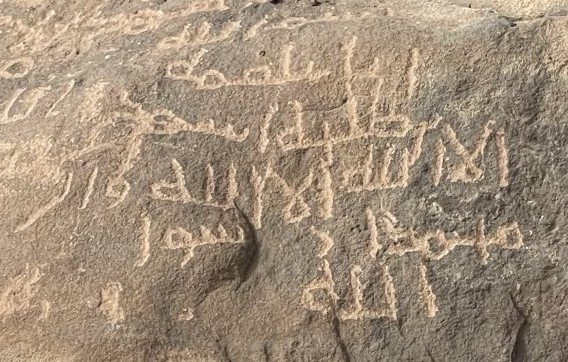

The evidence in question is an early Arabic inscription that was found in the region of al-Tabūk in Saudi Arabia, photographed by “Rāʿī al-Fāṭir” (@ahmed666551), and published on Twitter by Fahad bin Tahir (@fahadbintahir), which reads: “In the name of God. I am ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah. I testify that there is no god except God, and that Muḥammad is the Messenger of God.”

The potential significance of this inscription is spelled out by Fahad: there was reportedly an ultra-obscure Companion named ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah b. ʾabī Ṭalḥah who died at the Battle of al-Yarmūk (in 20/636),[27] so if indeed the inscription’s author was this ʿAlqamah, it would make “this [inscription one] of the oldest of Islamic inscriptions, older than the inscription of Salamah and [that of] Zuhayr.”[28]

What then are the potential implications of this early inscription for Donner’s thesis? Donner and his supporters argue that early Arabic or proto-Islamic media contain the Basmalah (“in the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful”) and the single Šahādah (“there is no god but God”), but consistently fail to mention the double Šahādah or the specifically-Islamic formula “Muḥammad is the Messenger of God”. The significance of this pattern of omission is spelled out by Donner as follows:

Certainly in later times—from perhaps the early second century AH/eighth century C.E. or a little later, by which date Islam had begun to coalesce from the Believers’ movement into a clearly defined and distinct religious confession—the recognition of Muhammad as prophet was the decisive marker that distinguished Muslims from Christians, Jews, and all others. By that time, to utter the “statement of faith” (shahada, literally, “bearing witness”) “There is no god but God, Muhammad is the apostle of God” (la ilaha illa llah, Muhammad rasul allah) was decisively to declare oneself a Muslim. But here again the early evidence is suggestive; the earliest documentary attestations of the shahada, found on coins, papyri, and inscriptions dating before about 66/685, include only the first part of the later “double shahada”: “There is no god but God” (sometimes with the addition, “who has no associate”)—Muhammad is not yet mentioned. If this is not merely an accident of preservation, we may see in it yet another indication of the ecumenical or non-confessional character of the early community of Believers, for the statement “There is no god but God” would have been acceptable to all monotheists, including Christians and Jews. It is not unreasonable to propose, then, that many Christians and Jews of Syria, Iraq, and other areas, as monotheists, could have found a place in the expanding early community of Believers.[29]

To put it simply: generic declarations that “there is no God but God” are consistent with both Judaism and Christianity; specific declarations that “Muḥammad is the Messenger of God” are indicative of a narrower or exclusive Islamic confessional identity; Arabic or proto-Islamic media up until 66/685 consistently contain the former rather than the latter; this is straightforwardly unexpected on the hypothesis that the movement or community producing this media already possessed a narrow or exclusive Islamic confessional identity (let alone one that was obsessed with Muḥammad); but it is consistent with the hypothesis that the movement or community producing this media constituted some kind of pan-Abrahamitic coalition (e.g., an ecumenical or confessionally-open “Community of Believers”).

In light of this, the potential challenge posed by the aforementioned inscription becomes clear: if indeed a double Šahādah was inscribed before the year 20/636, it breaks Donner’s posited pattern of evidence and indicates the existence of a narrow or exclusive Islamic confessional identity immediately after Muḥammad (d. 11/632) amongst his followers in Arabia.

In short, the authorship of this inscription by the Companion ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah b. ʾabī Ṭalḥah would seemingly pose a serious challenge to at least Donner’s version of the pan-Abrahamitic thesis. But what reason is there to accept that this inscription really was authored by the Companion ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah, rather than someone else by that name or indeed some modern forger? To this end, Fahad adduces two considerations:

Caution: without a full lineage or at least the name of his grandfather, I cannot be completely certain that the inscriber is [indeed] ʿAlqamah the Companion. However, this is [still] likely because the name ʿAlqamah is not amongst the names that are very common. Additionally, [there is] the style of the script.[30]

In other words, ʿAlqamah was a rare name in the early period, rendering the existence of another early author named “ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah” unlikely; and the style of the Arabic script used in the inscription is extremely archaic, which is consistent with its being an authentic early inscription.

I will accept the second point without question: according to Marijn van Putten (an authority on early Arabic), the inscription looks archaic and likely derives from some time in the 1st Century AH. However, I question Fahad’s first claim, concerning the rarity of the name ʿAlqamah. Even a cursory survey of some classical Arabic biographical dictionaries reveals more than three dozen figures named “ʿAlqamah” who lived at various points during the 1st Century AH:

ʿAlqamah al-Ḥaḍramī; a member of a delegation to the Prophet; father of someone named Kulṯūm.

ʿAlqamah b. Hilāl al-Ḵuzāʿī; father of a Companion named Kurz.

ʿAlqamah al-Firaʿī; father of a Companion named Zuhayr who lived in al-Ramlah.

ʿAlqamah al-Bajalī/al-Naḵaʿī; father of a Companion or Follower named Zuhayr who settled in Kufah.

ʿAlqamah; father of a Companion or Follower named Nāfiʿ who settled in Syria.

ʿAlqamah al-ʾAslamī; ʾAbū ʾAwfá; someone who sent ṣadaqah to the Prophet.

ʿAlqamah b. Nājiyah al-Ḵuzāʿī; ʾAbū Kulṯūm; a Madinan Companion who settled in the desert.

ʿAlqamah b. Mujazziz al-Mudlijī; an ʿāmil of the Prophet’s.

ʿAlqamah b. al-ʾAʿwar al-Sulamī; a Madinan Companion who transmitted to Ibn ʿAbbās.

ʿAlqamah b. al-Ḥāriṯ/al-Ḥuwayriṯ al-Ḡifārī; a Companion.

ʿAlqamah b. al-Faḡwāʾ b. ʿUbayd b. ʿAmr al-Ḵuzāʿī; a Companion who settled in Madinah; the Prophet’s guide to al-Tabūk.

ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah b. ʾabī Ṭalḥah; Hijazian; fought and died at al-Yarmūk; d. 20/636.

[This is the “ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah” being posited as the inscription’s author.]

ʿAlqamah b. Zāmil b. Marwān b. Zuhayr; someone who was present at the Battle of al-Yarmūk.

ʿAlqamah b. Sumayy al-Ḵawlānī; a Companion who settled in Egypt after the conquest thereof.

ʿAlqamah b. Rimṯah al-Balawī; settled in Egypt after the conquest thereof.

ʿAlqamah b. ʿUlāṯah b. ʿAwf b. al-ʾAḥwaṣ b. Jaʿfar b. Kullāb b. Rabīʿah b. ʿĀmir b. Ṣaʿṣaʿah; governor of Ḥawrān under ʿUmar.

ʿAlqamah b. ʾAsmayfaḥ b. Waʿlah al-Sabāʾī; an Egyptian who transmitted from Ibn ʿAbbās.

ʿAlqamah al-ʾAnmārī; father of a Kufan Follower named ʿAlī.

ʿAlqamah b. Sufyān al-Ṯaqafī; a member of the Ṯaqafī delegation to the Prophet; a Ṭāʾifī Companion who settled in Basrah.

[Possibly the same as: ʿAlqamah al-Ṯaqafī; a member of the Ṯaqafī delegation to the Prophet; father of a Companion named ʿAbd al-Raḥmān who settled in Kufah.]

ʿAlqamah b. Naḍlah b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʿAlqamah al-Kinānī/al-Kindī; a Companion or Follower who settled in Makkah; transmitted from ʿUmar.

ʿAlqamah b. Šabr; a companion of ʿUmar’s who settled in al-Madāʾin.

ʿAlqamah b. Šihāb al-Qušayrī; a Syrian Follower; father of Naṣr and Maḥfūẓ.

ʿAlqamah b. Junādah b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Qays; a Companion who settled in Egypt after the conquest; Muʿāwiyah’s walī al-baḥr; d. 59/678-679.

ʿAlqamah b. Yazīd b. ʿAmr; someone who came to the Prophet and then returned to Yemen; he was present for the conquest of Egypt; he lived under Muʿāwiyah.

ʿAlqamah b. Qays b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Mālik b. ʿAlqamah b. Salāmān b. Kahl b. Bakr b. ʿAwf b. al-Naḵaʿ; ʾAbū Šibl; Kufan; d. 61-65/680-685 or 72-73/691-693.

ʿAlqamah b. Waqqāṣ b. Miḥṣan b. Kaladah al-Layṯī; Madinan; died under ʿAbd al-Malik.

ʿAlqamah b. Bajālah b. al-Zibirqān; a Yemeni Follower who transmitted from ʾAbū Hurayrah.

ʿAlqamah b. Wāʾil b. Ḥujr al-Ḥaḍramī al-Kindī; a Kufan Follower.

ʿAlqamah b. ʿĀṣim; ʾAbū Šaʿīrah; an Egyptian who transmitted from ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ.

ʿAlqamah b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Sinān b. Nubayšah b. Salamah b. Salmān b. al-Nuʿmān b. Ṣubḥ b. Māzin; Basran; d. 100/718-719.

ʿAlqamah b. Hilāl al-Kalbī from the Banū Taym Allāh; someone whose grandfather came to the Prophet at al-Ḥudaybiyyah.

ʿAlqamah b. ʿAlī b. ʿAlqamah b. Šarīk b. al-Ḥāriṯ b. ʿĀṣim b. ʿUbayd b. Ṯaʿlab b. Yarbūʿ b. Ḥanẓalah; father of a Marwazī named ʾAṣbaḡ who studied under Saʿīd b. al-Musayyab and ʿIkrimah.

ʿAlqamah b. Marṯad al-Ḥaḍramī; ʾAbū al-Ḥāriṯ; Kufan; d. 120/737-738.

ʿAlqamah b. ʾabī ʿAlqamah Bilāl; his father Bilāl was the mawlá of ʿĀʾišah; Madinan; died under al-Manṣūr (r. 136-158/754-775).

ʿAlqamah al-Hamdānī; father of a Kufan traditionist named Ḵālid.

ʿAlqamah; the son of the Syrian ʾAbū ʿAlqamah Naṣr b. ʿAlqamah.

ʿAlqamah al-Māzinī; father of the Basran traditionist ʾAbū Muḥammad Maslamah.

The ostensible existence of dozens of early ʿAlqamahs is all the more significant when it is realised that the classical sources likely record the names of only a fraction of the Arab and Muslim population from this time period: for each cited ʿAlqamah, there are probably dozens more who went unmentioned in the sources. When combined with the fact that “Ṭalḥah” was an extremely common name (as Fahad seems to implicitly concede), it seems entirely plausible that there was an obscure or unmentioned figure named “ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah” who lived in—or passed through—the region of al-Tabūk during the second half of the 1st Century AH.

This is of course speculative, but so too is the identification of the inscriber ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah with the Companion ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah. In other words, there is no good reason to think that the inscriber was the Companion rather than someone else of the same name: pace Fahad, the latter cannot be ruled out in favour of the former, at least based on the available evidence. Consequently, the pre-20/636 provenance of this inscription cannot be demonstrated, which is to say: it cannot be precluded that the inscription actually derives from the later Zubayrid or Marwanid periods.

In short, this inscription is equivocal: it might be pre-20/636 and thus conflict with Donner’s thesis, but it might instead be post-66/685 and thus compatible therewith. As such, it cannot be counted as evidence against Donner’s thesis, which remains unaffected: as things stand, the securely-dated coins, inscriptions, and papyri of the 1st Century AH continue to conform thereto.

There is a more fundamental problem beyond all of this, however: the notion that this inscription, if genuinely inscribed by a Companion, would undermine Donner’s version of the pan-Abrahamitic thesis is predicated upon a false assumption. Donner’s hypothesis does not actually predict that we should find no pre-Marwanid or pre-Zubayrid instances of the double Šahādah or other such declarations of Muḥammad’s messengership. Instead, Donner’s hypothesis predicts that we should find no official pre-Marwanid or pre-Zubayrid instances of the double Šahādah and the like, since, on his view, it was the overall movement that was pan-Abrahamitic. Donner has always accepted that some of Muḥammad’s early followers regarded him to be the Messenger of God: after all, Donner explicitly accepts that the Quran is “the most important source of information about the early community of Believers”[31] and that Muḥammad “is called [therein], above all, messenger or apostle (rasul), that is, God’s messenger, and prophet (nabi).”[32] Donner even explicitly affirms that the basic belief “that Muhammad was the man who, as God’s apostle or prophet, was guiding them” would have been widespread amongst his early followers.[33] Donner’s view is thus not that no one regarded Muḥammad to be the Messenger of God until the Zubayrid or Marwanid periods, but rather, that Muḥammad founded and led a pan-Abrahamitic coalition (an ecumenical or confessionally-open “Community of Believers”) that included both proto-Muslims or Arabian “new monotheists” (who recognised him to be the Messenger of God and adhered to Quranic law) and some Jews and Christians (who recognised his political and military leadership but continued to adhere to their own scripture).[34]

In short, it is the official media for the early movement as a whole that one would expect to embody generic monotheism on Donner’s view. By contrast, it would not be unexpected to find private or personal media from some of the proto-Muslim “new monotheists” reflecting their long-held belief that Muḥammad was the Messenger of God—and, as it happens, the inscription under consideration is a graffito (i.e., as far from official as one can get). Thus, even if inscribed by the Companion ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah, this inscription is entirely compatible with Donner’s version of the pan-Abrahamitic thesis: only a misunderstanding or mischaracterisation thereof—a strawman notion that Donner posits an absence of any early belief in Muḥammad’s messengership altogether—would conflict with such evidence.

This is so regardless of what Donner himself has actually said on the matter: this is simply what the view he outlined implies or entails, regardless of whether he understood or appreciated such implications or entailments. As it happens, however, an emphasis on official media is already present in Donner’s own statements:

Beginning around the time of ʿAbd al-Malik, however—in the last quarter of the first century AH/end of the seventh century C.E.—we find Muhammad’s name mentioned with increasing frequency in the Believers’ official documents; moreover, these references suggest that identification with Muhammad and his mission and revelation was coming to be seen as constitutive of the Believers’ collective identity. The first inscriptions of any kind to carry the phrase “Muhammad is the Apostle of God” are coins from Bishapur (Fars), apparently issued in 66/685-686 and 67/686-687 by a governor for the Zubayrids, so it may be that the Umayyads were inspired to emphasize the role of the prophet by their rival ʿAbdullah ibn al-Zubayr, known, as we have seen, for his stern piety. Whatever its inspiration, ʿAbd al-Malik and his entourage seem to have advanced this process energetically and in several media. The Dome of the Rock inscriptions lay considerable emphasis on Muhammad’s position as prophet; but more telling is the appearance on coins, from the time of ʿAbd al-Malik onward, of the full “double shahada,” that is, the combining of the phrase “There is no god but God” with the phrase “Muhammad is the apostle of God” as a decisive marker of the character of the issuing authority.[35]

From all of this, it seems clear that, for Donner, the key shift in the Believers’ polity—at that point comprising the rulers and the army of the early caliphate—towards an exclusivist Islamic confessional identity occurred in official media, which is taken either to reflect or to have facilitated a general transformation of the movement as a whole (including the absorption, marginalisation, or redefinition of its former Jewish and Christian members).[36] In short, it is official media, rather than private or personal expressions of belief, that really matter for Donner’s thesis.

On a final point of interest: if the ʿAlqamah inscription was indeed created before 20/636, it would demonstrate that the double Šahādah had already been standardised immediately after Muḥammad’s death.[37] In other words, it would mean that the familiar double Šahādah that appears ubiquitously in sources and media from the Marwanid period onward actually existed all along, rather than being created later by the Zubayrids or the Marwanids as a kind of addendum or reworking of the single Šahādah. In conjunction with the consistent appearance of the single Šahādah in official media prior to 66/685, this would imply that two standardised creedal statements coexisted in the proto-Islamic movement for half a century: a more general statement of monotheism in formal contexts (neutrally embodying the “Community of Believers” overall, as Donner would have it), and a more exclusive or restrictive statement that was circulating sub-officially amongst those who specifically recognised Muḥammad’s messengership (i.e., Donner’s “new monotheists”).

To recapitulate and summarise:

- Donner’s version of the pan-Abrahamitic thesis is widely accepted in mainstream scholarship.

- Donner appeals to the generic monotheism of Arabic or proto-Islamic media up until the Zubayrid and Marwanid periods as part of his evidence that the proto-Islamic movement was an ecumenical or confessionally-open “Community of Believers”.

- An early inscription containing the specifically-Islamic double Šahādah has been adduced against Donner’s thesis.

- The identification of the inscriber thereof, ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah, with a Companion of the same name is highly questionable, given that there were plausibly other figures by the same name who could have produced the inscription (e.g., during the Zubayrid or Marwanid periods).

- Even if the inscriber was the Companion named ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah (who died in 20/636), this would still be compatible with Donner’s thesis, since Donner has always accepted that some early members of the Believers’ movement regarded Muḥammad to be the Messenger of God. Donner’s thesis really relies upon the absence of exclusively-Islamic declarations in the official media of the proto-Islamic polity (i.e., the media reflecting or embodying the Believer’s movement as a whole), rather than the private or personal beliefs of some members of the movement per se.

In short, even if Donner’s thesis is ultimately rejected, this inscription cannot be reasonably counted as good evidence against it.

* * *

I owe thanks to Mehrab, abcshake, Marijn van Putten, and especially Yet Another Student, for their generous support over on my Patreon. I also owe special thanks to Marijn for his extremely helpful insights and feedback for this article.

[1] For a summary, see https://islamicorigins.com/the-new-historiography-of-islamic-origins/

[2] Patricia Crone & Michael A. Cook, Hagarism: The making of the Islamic world (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1977), part 1.

[3] Michael A. Cook, Muhammad (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1983), 75-76.

[4] Patricia Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press, 1987), 244, 247-248.

[5] Fred M. Donner, “From Believers to Muslims: Confessional Self-Identity in the Early Islamic Community”, Al-Abhath, Volume 50-51 (2002-2003), 9-53.

[6] Id., Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam (Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press, 2010), esp. ch. 2.

[7] E.g., Brooke O. Vuckovic, Heavenly Journeys, Earthly Concerns: The Legacy of the Miʿraj in the Formation of Islam (New York, USA: Routledge, 2005), 42-43; Reuven Firestone, An Introduction to Islam for Jews (Philadelphia, USA: The Jewish Publication Society, 2010), 53; Chase F. Robinson, “The rise of Islam, 600-705”, in Chase F. Robinson (ed.), The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 189 (incl. n. 38); Stephen J. Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad’s Life and the Beginnings of Islam (Philadelphia, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), ch. 4; Robert G. Hoyland, In God’s Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015), 57-60, 197; Harry Munt, ““No two religions”: Non-Muslims in the early Islamic Ḥijāz”, Bulletin of SOAS, Volume 78, Number 2 (2015), 251, n. 5; Juan Cole, Muhammad: Prophet of Peace amid the Clash of Empires (New York, USA: Bold Type Books, 2018), passim; Ilkka Lindstedt, “The Makings of Early Islamic Identity”, Freedom to Think! HCAS blog (9th/October/2019): https://blogs.helsinki.fi/hcasblog/2019/10/09/the-makings-of-early-islamic-identity/; Mostafa Abedinifard, “Ridicule in the Qur’an: The Missing Link in Islamic Humour Studies”, in Bernard Schweizer, Lina Molokotos-Liederman, & Yasmin Amin (eds.), Muslims and Humour: Essays on Comedy, Joking, and Mirth in Contemporary Islamic Contexts (Bristol, UK: Bristol University Press, 2022), 30.

[8] Sean W. Anthony, Muhammad the Empires of Faith: The Making of the Prophet of Islam (Oakland, USA: University of California Press, 2020), 17, n. 63. Also see https://twitter.com/shahansean/status/1580003613396860929?s=46

[9] Nicolai Sinai, ‘The Unknown Known: Some Groundwork for Interpreting the Medinan Qur’an’, Mélanges de l’Université Saint-Joseph, Volume 66 (2015-2016), 47-96.

[10] Jonathan E. Brockopp, Muhammad’s Heirs: The Rise of Muslim Scholarly Communities, 622-950 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 15-16.

[11] Jack Tannous, The Making of the Medieval Middle East: Religion, Society, and Simple Believers (Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press, 2018), 293-294 (incl. n. 130), 304.

[12] Patricia Crone, “Among the Believers: A new look at the origins of Islam describes a tolerant world that may not have existed”, Tablet (10th/August/2010): http://tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/42023/among-the-believers

[13] Brockopp, Muhammad’s Heirs, 38-39, 48-50; Jack Tannous, The Making of the Medieval Middle East, passim.

[14] Michael P. Penn, Envisioning Islam: Syriac Christians and the Early Muslim World (Philadelphia, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 180.

[15] See Donner and Cole, cited above.

[16] See Crone & Cook, Hagarism, 7-8; Donner, Muhammad, 72-73, 227 ff.

[17] I.e., pseudo-Sebēos, The Secrets of Rabbi Šimʿōn, and the Ten Kings Midrash; see Crone & Cook, Hagarism, 4-8; Donner, Muhammad, 114; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, 27 ff., 199 ff.

[18] I.e., The Secrets of Rabbi Šimʿōn and related Jewish traditions; see Crone & Cook, Hagarism, 4-5; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, 27 ff.

[19] I.e., John bar Penkaye; see Donner, “From Believers to Muslims”, 43-45; id., Muhammad, 113-114, 176.

[20] I.e., the Maronite chronicle; see Crone & Cook, Hagarism, 11.

[21] I.e., the disputation of the patriarch and the emir, and the correspondence between Leo and ʿUmar; see Crone & Cook, Hagarism, 14-15; Patricia Crone, “Jāhilī and Jewish law: the qasāma”, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, Volume 4 (1984), 179.

[22] See Donner, Muhammad, 98-99, 176-177; Lindstedt, “The Makings of Early Islamic Identity”.

[23] See Donner, Muhammad, 111-112, 205-206.

[24] See Crone, “Jāhilī and Jewish law”, 178-179. Also see Brockopp, Muhammad’s Heirs, 38-39, 48-50, 58.

[25] See Suliman Bashear, “Qibla Musharriqa and Early Muslim Prayer in Churches”, The Muslim World, Volume 81, Numbers 3-4 (1991), 267-282; Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet, 215.

[26] See Donner, Muhammad, 176, 180-181, 212, 221-222, 252. Also see Hoyland, In God’s Path, 165-167.

[27] Muḥammad b. Hišām al-Kalbī (ed. Muḥammad Ḵalīfah al-Tūnisī), Jamharat ʾAnsāb al-ʿArab (Kuwait: Maṭbaʿat Ḥukūmat al-Kuwayt, 1983), p. 12: “And ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah: he was killed on the Day of al-Yarmūk.” Also see Ibn al-ʾAṯīr (ed. Muḥammad ʾIbrāhīm al-Bannā et al.), ʾUsd al-Ḡābah fī Maʿrifat al-Ṣaḥābah, vol. 3 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Fikr, 1989), p. 582: “ʿAlqamah b. Ṭalḥah b. ʾabī Ṭalḥah; the brother of ʿUṯmān b. Ṭalḥah, whose lineage was mentioned previously; he converted to Islam and had Companionship, and he died as a martyr on the Day of al-Yarmūk.” I was able to find no other sources referring to this figure.

[28] https://twitter.com/fahadbintahir/status/1561017214504951810?s=20

[29] Donner, Muhammad and the Believers, 111-112.

[30] https://twitter.com/fahadbintahir/status/1564693034956095488?s=20

[31] Donner, Muhammad, 53.

[32] Ibid., 75.

[33] Ibid., 77.

[34] Ibid., e.g., 87.

[35] Donner, Muhammad, p. 205. Emphasis mine.

[36] Also see ibid., 220 ff.

[37] I owe thanks to Marijn van Putten for this point.