There is an infamous story about the great Arab conquests and the destruction of books, which is popularly cited by Islamophobes to show that Muslims are intolerant zealots or philistines who hate science, etc. The story goes that, when the Arab armies conquered Persia, they found libraries of Persian books. The Arab commander, Saʿd b. ʾabī Waqqāṣ, was not sure what to do with these books, so he sent a letter to Caliph ʿUmar. ʿUmar responded by commanding him to destroy the books, because: if they contained guidance, they were superfluous (due to God’s having sent the Quran), and could be destroyed; and if they contained error, they should be destroyed. Therefore, it was best to destroy them.

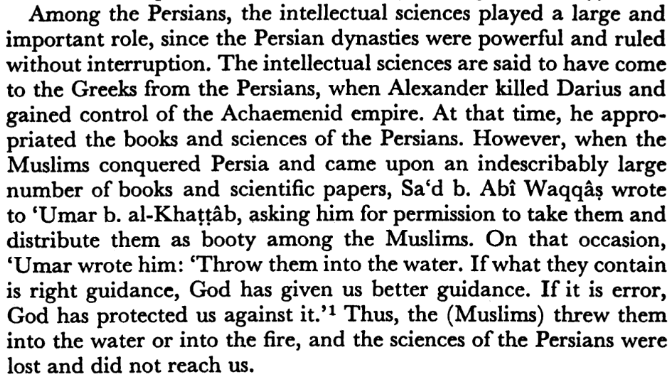

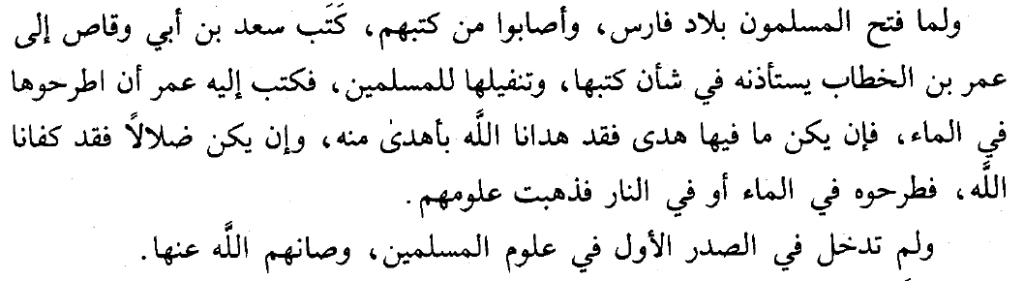

For example, the following is recorded in the Muqaddimah of Ibn Ḵaldūn, here translated by Franz Rosenthal:

This story has several problems: it knows the personal correspondence between Saʿd and ʿUmar, and it ascribes a clever, sophistic, ‘decision theory’ argument (akin to Pascal’s Wager) to ʿUmar. Are we really to believe that ʿUmar wrote in such a witty way? The dialogue seems very literary to me, e.g., the sort of thing a litterateur (or a character in a book) would say, rather than a gruff conqueror out in the sticks. Also, are we really to believe that these letters were preserved over the course of the conquests? I’m skeptical.

There is a much bigger problem, however: the story is recorded very late. Of course, all extant Islamic historical reports are recorded late: most extant Islamic literature dates from around 800 CE onward, which has famously given rise to debates about their authenticity. But the story of Saʿd and ʿUmar is recorded really late.

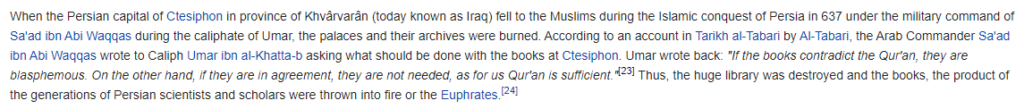

I first encountered this story in Rosenthal’s English translation of the Muqaddimah of the famous North African polymath Ibn Ḵaldūn (d. 1406 CE), and until recently, I had never encountered any earlier version. Imagine my surprise, then, when I happened to find the following on Wikipedia:

I checked the references on the Wikipedia page, which led to a secondary rather than primary source: Zeidan, pp. 42–47. I then checked the bibliography on the Wikipedia page, which yielded the following: Zeidan, Georgie, The History of the Islamic Civilization, III.

The lack of publishing details (no press, no date) made finding this source difficult, but after Googling for a bit, I figured out that this is not an English book at all. This is actually the Taʾrīḵ al-Tamaddun al-ʾIslāmiyy (1901–1906) of Jurjī Zaydān, a Lebanese intellectual who died in 1914. I managed to find a PDF of volume 3 of this work, and although the page numbers from Wikipedia (pp. 42–47) did not yield the desired result, I was able to search the PDF with keywords, until I found the story of Saʿd and ʿUmar (p. 57).

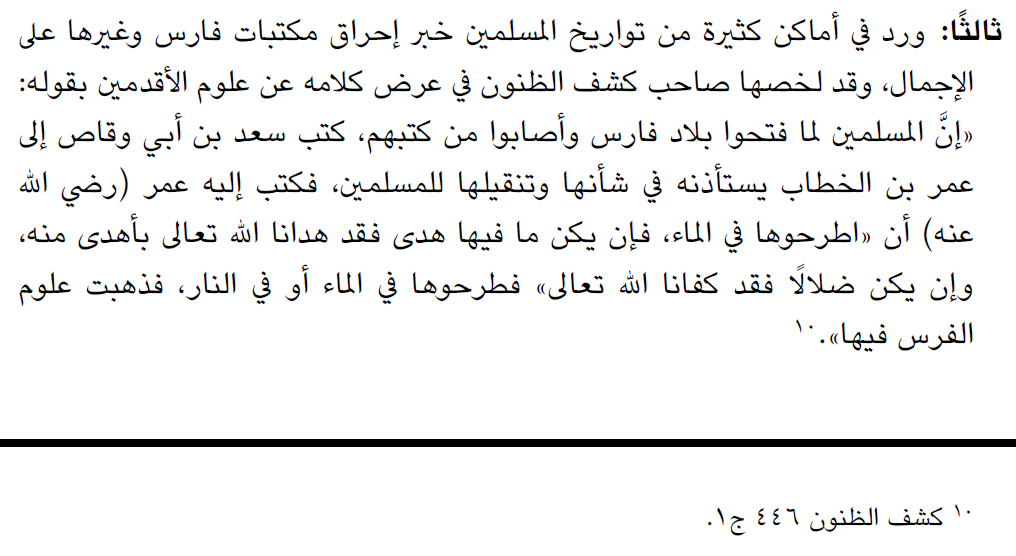

And of course, Zaydān does not cite al-Ṭabarī. Instead, he cites the Kašf al-Ẓunūn of the Ottoman polymath Kâtip Çelebi, aka, Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah (d. 1657 CE).

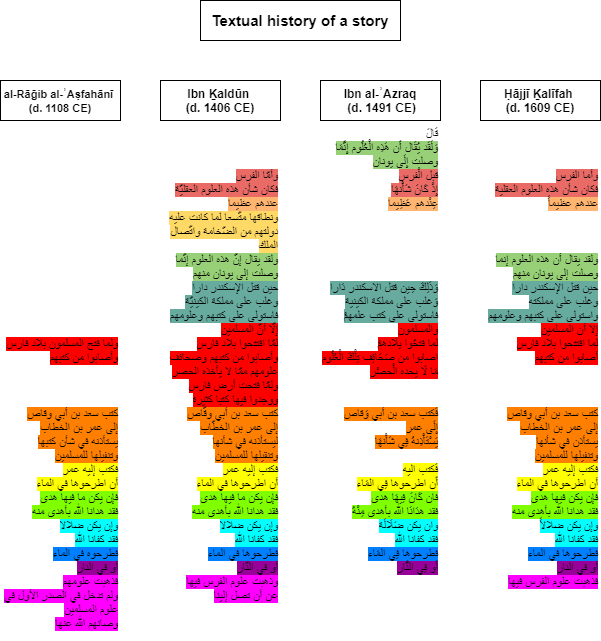

To make absolutely sure, I searched through digital versions of both English and Arabic editions of al-Ṭabarī’s Taʾrīḵ, to no avail. I then searched the entire Shamela Arabic database, which yielded some interesting results: this story appears in four premodern sources and does predate Ibn Ḵaldūn, but it is still very late.

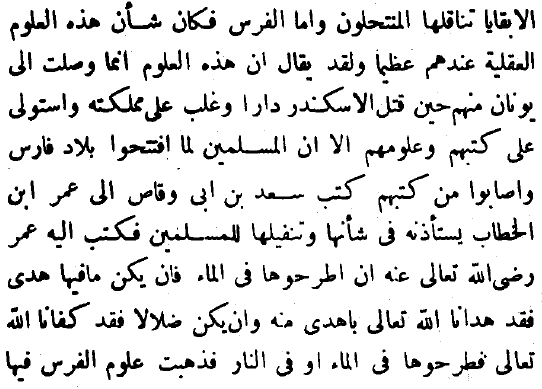

The earliest version that I have found thus far in al-Mufradāt fī Ḡarīb al-Qurʾân by the Persian scholar al-Rāḡib al-ʾAṣfahānī (d. 1108 CE), around four centuries after the Arab conquest of Persia.[1]

The story then appears three centuries later in the Muqaddimah of Ibn Ḵaldūn (d. 1406 CE), who prefaces it with a story about Alexander the Great.[2]

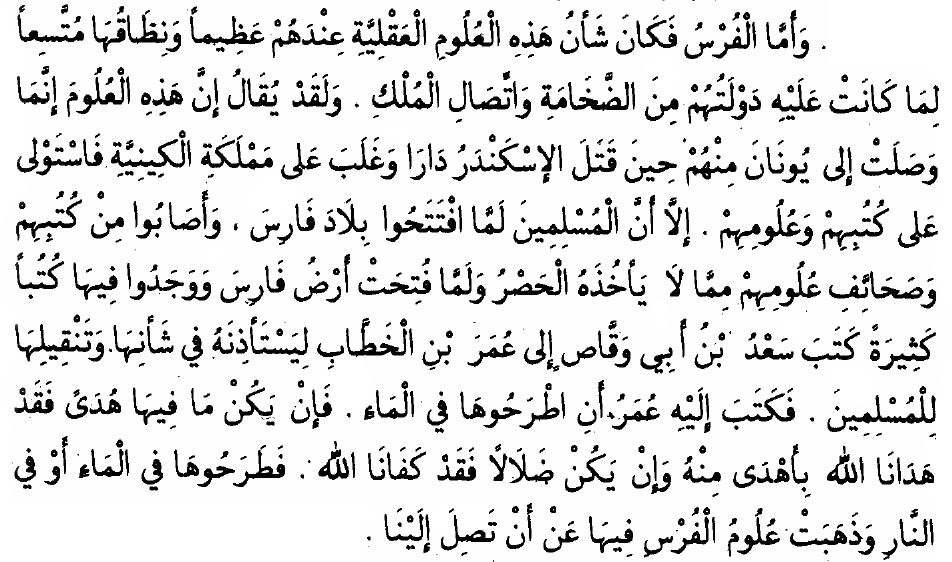

The story also shows up in the Badāʾiʿ al-Silk fī Ṭabāʾiʿ al-Mulk of the Andalusian scholar Ibn al-ʾAzraq (d. 1491 CE), who appears to be quoting Ibn Ḵaldūn’s Muqaddimah (as the editor notes in the footnotes), including the part about Alexander.[3]

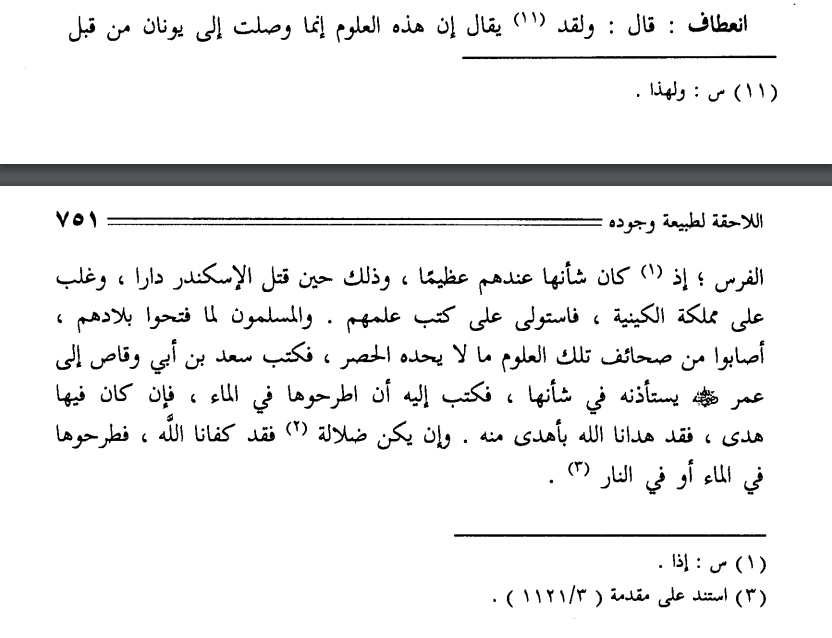

Finally, the story appears in the Kašf al-Ẓunūn of the famous Ottoman polymath Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah (d. 1609 CE), who is most certainly quoting Ibn Ḵaldūn (same elements, same order).[4]

Here is a diagram I made showing the similarities between these texts:

(An Egyptian remix of this story featuring the Library of Alexandria was also created to justify Saladin’s destruction of the Fatimid library in Cairo; see my companion article thereto.)

Given all of this, why does Wikipedia claim that this story was recorded by al-Ṭabarī? By Googling excerpts of the Wikipedia quote, I found that the earliest instance of the wording is from a 1996 or 2000-2001 presentation by Dr. Daryoush Jahanian, transcribed on the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies website:

Jahanian cites Zaydān and appears to be the one who translated this passage therefrom, and he correctly noted that Zaydān was quoting Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah. (He also mentions Ibn Ḵaldūn.) Thus, the erroneous attribution to al-Ṭabarī must postdate Jahanian’s translation of the passage.

The prime suspect is Dr. Gianpaolo Savoia-Vizzini, who wrote an article in 2000 that appears on the very same website. He paraphrases Jahanian’s translation of Zaydān’s quotation of Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah, without citing Jahanian or Zaydān, and instead cites al-Ṭabarī!

This quote was first added to Wikipedia on the 19th of November, 2009, and it was identical to Savoia-Vizzini’s version:

In other words, it was Savoia-Vizzini’s recension of Jahanian’s translation that appeared on Wikipedia, including Savoia-Vizzini’s erroneous attribution to al-Ṭabarī. But the plot thickens! A few minutes after this quote was added to Wikipedia, it was given the “Zeidan, p. 42-47” reference:

This is perplexing: Savoia-Vizzini mentioned al-Ṭabarī but gave no reference, whereas “Zeidan p 42-47” is from Jahanian’s endnotes, where Jahanian clearly indicates that the ultimate source is Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah. To make things even more complicated, an addendum that is absent from Savoia-Vizzini’s recension but similar to the final part of Jahanian’s original translation was added on the 21st of November, 2009!

In other words, the Wikipedia editor took Savoia-Vizzini’s recension and mention of al-Ṭabarī, added part of Jahanian’s original reference (Zeidan), and then added a paraphrase of the final part of Jahanian’s original translation.

This is getting complicated, so let’s do a recap:

- The story first appears with al-Rāḡib (d. 1108) in Persia.

- It travels to North Africa, where it is repeated by Ibn Ḵaldūn (d. 1406).

- Ibn Ḵaldūn’s work is then cited in Spain, by Ibn al-ʾAzraq (d. 1491), and in Istanbul, by Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah (d. 1609).

- Then, between 1901 and 1906, Zaydān (d. 1914) cited Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah’s version.

- Then, in 1996 or 2000, Jahanian translated Zaydān’s version and cited Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah as well.

- Then, in 2000, Savoia-Vizzini paraphrased Jahanian and misattributed it to al-Ṭabarī.

- Then, in 2009, Savoia-Vizzini’s version and misattribution was added to Wikipedia, along with Jahanian’s “Zeidan” reference and part of Jahanian’s version.

And, ever since, hordes of Islamophobes have gleefully regurgitated this quote from Wikipedia (as in this seething tirade directed against a certain “Scott in Dallas”).

As far as I can tell, this story appears in no early source (i.e., no source between 600 and 1000 CE). Certainly, it seems very unlikely to represent a genuine historical memory. Instead, it seems like a witty ‘just-so’ story composed by a Persian to explain the relative paucity of pre-Islamic Persian material in Arabic science (compared to the colossal amount of pre-Islamic Greek material).

I am sure that many books were incidentally destroyed during the Arab Conquests, as in most conquests. But the notion of a systemic, religiously-motivated Arab Muslim effort to destroy infidel Persian knowledge cannot be justified merely on the basis of this story.

Of course, all of this is provisional – it is certainly possible that the story could turn up in a relatively early source. As it stands, however, the story simply seems to be untrue.

* * *

For the original Twitter thread upon which this article is based, see:

https://twitter.com/IslamicOrigins/status/1255921987182039040?s=20

[1] Al-Rāḡib al-ʾAṣfahānī (ed. Ṣafwān ʿAdnān al-Dāwūdī), al-Mufradāt fī Ḡarīb al-Qurʾân (Damascus, Syria: Dār al-Qalam, 2009), p. 30.

[2] Ibn Ḵaldūn (ed. Ḵalīl Šihādah & Suhayl Zakkār), Taʾrīḵ, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Fikr, 1988), p. 631.

[3] Ibn al-ʾAzraq (ed. ʿAlī Sāmī al-Naššār), Badāʾiʿ al-Silk fī Ṭabāʾiʿ al-Mulk, vol. 2 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār al-ʾIslām, 2008), pp. 750-751.

[4] Ḥājjī Ḵalīfah (ed. Muḥammad Sherefettin Yaltkaya), Kašf al-Ẓunūn ʿan ʾAsāmī al-Kutub wa-al-Funūn, vol. 1 (Dār ʾIḥyāʾ al-Turāṯ al-ʿArabiyy, n.d.), p. 379.