There is a classic debate in some modern scholarship on the history of early Arabic scholarship and learning: when did Arabic scientific writing commence? More specifically, the debate is about which caliph oversaw the first translation of ‘foreign’ scientific, philosophical, and related works into Arabic (i.e., the famous Arabic translation movement): was it an Umayyad caliph or an Abbasid caliph?

This debate is most notably embodied in two conflicting publications:

- Dimitri Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ʿAbbāsid society (2nd-4th/8th-10th centuries) (London, UK: Routledge, 1999), ch. 2.

- George Saliba, Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance (Cambridge, USA: The Massachusetts Institute for Technology Press, 2007), chs. 1-2.

On the one hand, George Saliba argued that the first translations commenced under the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 685-705 CE), in connection to the famous Arabicisation of the imperial bureaucracy around that time. Saliba argued this on the basis of a story recorded in the Fihrist of al-Nadīm (d. c. 995 CE), a story recorded in the ʾAwāʾil of al-ʿAskarī (d. post-1005 CE), and the sophistication of Arabic translations already at the beginning of the Abbasid period.

On the other hand, Dimitri Gutas argued that the first translations commenced under the Abbasid caliph al-Manṣūr (r. 754-775 CE), in connection to lingering Sasanid traditions of imperial patronage and legitimacy. Gutas argued this primarily on the basis of four Arabic reports, recorded in:

- The Murūj al-Ḏahab of al-Masʿūdī (d. 956 CE)

- The Ṭabaqāt of Ṣāʿid al-ʾAndalusī (d. 1070 CE)

- The ʿUyūn al-ʾAnbāʾ of Ibn ʾabī ʾUṣaybiʿah (d. 1270 CE)

- The Muqaddimah of Ibn Ḵaldūn (d. 1406 CE)

Al-Masʿūdī’s report is an auto-biographical anecdote narrated by an earlier historian named Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Ḵurāsānī, who was close with the Abbasid caliph al-Qāhir (r. 932-934 CE). According to Muḥammad, al-Qāhir demanded that he recount to him the true history of the Abbasids, which Muḥammad obliged. When he came to Caliph al-Manṣūr in this recounting, Muḥammad reportedly stated the following:

He was the first caliph [who] associated with astrologers and acted upon the judgements of the stars. The Zoroastrian astrologer Nawbaḵt (who converted to Islam at his hands, and was the progenitor of those [known as] the Nawbaḵtiyyah), the astrologer ʾIbrāhīm al-Fazārī (the author of the qaṣīdah about stars, and other [topics] from the sciences of the stars and the configurations of the celestial sphere), and the astrologer ʿAlī b. ʿĪsá al-ʾAsṭurlābī were [all] with him [at his court]. He was the first caliph for whom books from foreign language[s] were translated into Arabic, among them: the Kitāb Kalīlah wa-Dimnah and the Kitāb al-Sind Hind. The books of Aristotle were translated for him, including the manṭiqiyyāt and others. The Kitāb al-Majisṭī of Ptolemy was translated for him, and Euclid’s book, and the Kitāb al-ʾAriṯmāṭīqī, and the rest of the ancient books, from Greek, Latin, Pahlavi, Persian, and Syriac. [These works] were dispersed amongst the people, who examined them and became devoted to their knowledge. During his reign [also], Muḥammad b. ʾIsḥāq created the Kitāb al-Maḡāzī wa-al-Siyar wa-ʾAḵbār al-Mubtadaʾ, which were not collected, nor known, nor written before that.[1]

In other words, according to Muḥammad b. ʿAlī, al-Manṣūr was responsible for the following innovations:

- He was the first to split the Banū Hāšim into conflicting Abbasid and Talibid factions.

- He was the first to patronise astrologers.

- He was the first to patronise the translation of foreign knowledge.

- Under him, the first Islamic biography of the Prophet was composed.

- He was the first to hand over high government offices to non-Arabs.

Gutas treats al-Masʿūdī’s report as the earliest available source on the genesis of the Arabic translation movement, but back in 2015 (when I was researching this subject), I somehow discovered an even earlier source: the Mušākalat al-Nās, a short treatise by al-Yaʿqūbī (d. post-905) summarising the innovations of caliphs. This work is a simple prosopographical list, seemingly in the words of the author—it is not a narrative, nor a collection of narratives. I have no memory of how I first encountered this text, but I when I read it, I was struck by his entry on Caliph al-Manṣūr:

He was the first caliph [who] utilised astronomers and acted upon the stars. He was the first [who] translated foreign books and translated them into the Arabic language. During his reign, the Kitāb Kalīlah wa-Dimnah was translated, and the Kitāb al-Sind Hind was translated, and the books of Aristotle, and the Kitāb al-Majisṭī of Ptolemy, and Euclid’s book, and the Kitāb al-ʾAriṯmāṭīqī, and the rest of the foreign books concerning the stars, arithmetic, medicine, philosophy, and other [topics] were [all] translated, and people [far and wide] examined them. And during his reign also, Muḥammad b. ʾIsḥāq b. Yasār created works of al-Maḡāzī, which were not collected or known before that.[2]

In other words, according to al-Yaʿqūbī, al-Manṣūr was responsible for the following innovations:

- He was the first to split the Banū Hāšim into conflicting Abbasid and Talibid factions.

- He was the first to patronise astrologers.

- He was the first to patronise the translation of foreign knowledge.

- Under him, the first Islamic biography of the Prophet was composed.

- He was the first to hand over high government offices to non-Arabs.

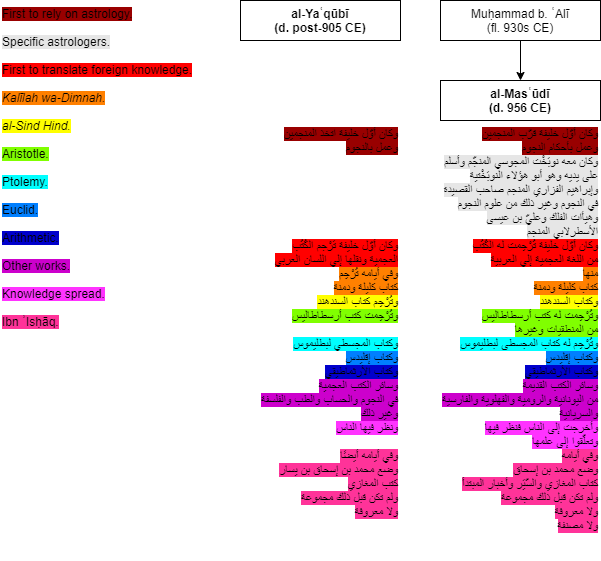

Déjà vu – this is exactly the same sequence that we just encountered in the story recorded half a century later by al-Masʿūdī! Here is a side-by-side comparison of the science-related parts of the texts in Arabic, a visual breakdown of the similarities and differences between these texts:

Here is another comparison of the texts, this time showing the omissions and additions therebetween:

There is no question about it: these texts are very closely related: either one was derived from the other, or both descend from a recent common ancestor. This connection was already noted by William Millward in 1964, who documented 43 parallel traditions between al-Yaʿqūbī and al-Masʿūdī. He concluded that both were drawing on a single, earlier, unspecified common source, rather than directly one from the other.[3]

Given that al-Yaʿqūbī’s version is (1) attested earlier and (2) simpler, his has the better claim to representing the original in the case of the tradition about al-Manṣūr, in my opinion. By contrast, al-Masʿūdī’s version is framed as the verbatim quote of an interlocutor in the middle of a conversion, which is very dubious: absent stenographers, it is fairly certain that historical quotes are literally fictitious, even if the underlying content is authentic.

In this particular case, the story is even more dubious: the caliph’s demand is suspiciously convenient, since it provides the story with an excuse for a character to provide a lengthy ‘exposition dump’ regarding the Abbasids. This is actually a fairly well-known tendency in early Arabic traditions and storytelling: historical and doctrinal expositions are framed within discussions and other such scenarios, to give them verisimilitude or an ‘authentic touch’.[4]

Thus, regardless of whether there truly was some kind of conversation involving Caliph al-Qāhir and a court historian, either al-Masʿūdī or the story’s ostensible narrator (Muḥammad b. ʿAlī) probably fashioned the section on al-Manṣūr out of a pre-existing written source.

It was common in early Arabic reports for tradents, collectors, and writers to rework and remix earlier material, even without acknowledgement. This is nicely summarised by Gerald Hawting, in a critical review of a book by Harald Motzki:

Motzki seems to have little time for the effects of the continuous reworking of the tradition, the introduction of glosses and improvements, the abbreviation and expansion of material, the linking together of reports which originated independently, the adaptation of traditions which originate in one context with a particular purpose so that they may be used in another, let alone simple errors of scribes and narrators. One cannot rule out real forgery but what that might be in a society which revered authority and tradition above independence and innovation is not obvious. Students of the historical tradition (taʾrīkh) have been able to demonstrate the way in which the tradition could be manipulated to give significantly different messages even after it had been recorded in writing (cf., for example, the way in which al-Ṭabarī was used by the later compilers like Ibn al-Athīr). This sort of creative reinterpretation must have been much more possible in the stages before the appearance of written texts.[5]

For a case in point, al-Masʿūdī’s version has undergone noticeable elaboration: it has been situated in an elaborate scenario, and it incorporates more details about al-Manṣūr’s patronage of astrologers. The original text was not simply copied—it was ‘improved’.

In short, al-Yaʿqūbī’s prosopographical treatise is the earliest source that I am aware of concerning the genesis of the Arabic translation movement, and through comparison with al-Masʿūdī’s later chronicle, illustrates the way in which traditions could be subject to growth and elaboration—even as late as the turn of the 10th Century CE, in a time of systematic written transmission.

* * *

For the original Twitter thread upon which this article is based, see: https://twitter.com/IslamicOrigins/status/1344279693827190785?s=20

[1] ʿAlī b. al-Ḥusayn al-Masʿūdī (ed. Charles A. C. Barbier de Meynard), Les Prairies d’Or: Texte et Traduction, Tome Huitième (Paris, France: Imprimerie Nationale, 1874), pp. 290-291. For an alternative translation, see id. (trans. Paul Lunde & Caroline Stone), The Meadows of Gold: The Abbasids (London, UK: Kegan Paul International, 1989), 388.

[2] ʾAḥmad b. ʾabī Yaʿqūb al-Yaʿqūbī (ed. Maḍyūf al-Farrā), Kitāb Mušākalat al-Nās li-Zamāni-him wa-mā yaḡlibu ʿalay-him fī kull ʿaṣr, in Majallat Markaz al-Buḥūṯ al-Tarbawiyyah (Doha, Qatar: University of Qatar, 1993), pp. 203-204. For an alternative translation, see id. (trans. William G. Millward), ‘The Adaptation of Men to Their Time: An Historical Essay by al-Yaʿqūbī’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Volume 84, Number 4 (1964), 338, col. 2.

[3] Millward, in ibid., 331-332.

[4] For more on these kinds of fictional narrative or literary features and framing in early Arabic reports, see especially Herbert Berg, The Development of Exegesis in Early Islam: The Authenticity of Muslim Literature from the Formative Period (Richmond, UK: Curzon Press, 2000), 17, and Pavel Pavlovitch, The Formation of the Islamic Understanding of Kalāla in the Second Century AH (718–816 CE): Between Scripture and Canon (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2015), 49-52.

[5] Gerald R. Hawting, ‘Harald Motzki: Die Anfänge der islamischen Jurisprudenz: ihre Entwicklung in Mekka bis zur Mitte des 2./8. Jahrhunderts’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Volume 59, Issue 1 (1996), 142, col. 2.