I was asked on Twitter to apply an isnad-cum-matn analysis to the famous “Hadith of the Cloak”, an exegetical hadith relating to Q. 33:33. There are actually several hadiths that seem to be referred to as such, including a tradition attributed to ʾUmm Salamah, and another attributed to ʿĀʾišah. In this article, I will be looking at the latter.

The hadith in question can be found in various Sunnī Hadith collections, in many versions, although the gist is normally the same: according to ʿĀʾišah, the Prophet wore a black camel-hair cloak on morning, and successively placed it on Ḥasan, Ḥusayn, Fāṭimah, and ʿAlī. For example, the following is recorded in the Ṣaḥīḥ of Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 261/875):

ʾAbū Bakr b. ʾabī Šaybah and Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Numayr related to us (and the wording is ʾAbū Bakr’s)—they said: “Muḥammad b. Bišr related to us, from Zakariyyāʾ, from Muṣʿab b. Šaybah, from Ṣafiyyah bt. Šaybah, who said: “ʿĀʾišah said: “The Prophet departed one morning wearing a black camel-hair cloak (wa-ʿalay-hi mirṭ muraḥḥal min šaʿar ʾaswad); then al-Ḥasan b. ʿAlī came and he placed [it on] him; then al-Ḥusayn came and he placed it on [him]; then Fāṭimah came and he placed [it on] her; then ʿAlī came and he placed [it on] him; then he said: “God only wants to remove any uncleanness from you, the People of the House, and to thoroughly purify you [Q. 33:33].””[1]

Naturally, the hadith is used in Sunnī-Šīʿī debates, since it can be interpreted as conveying a deep symbolism, with the Prophet passing his mantle to his family, called “the People of the House” (ʾahl al-bayt).

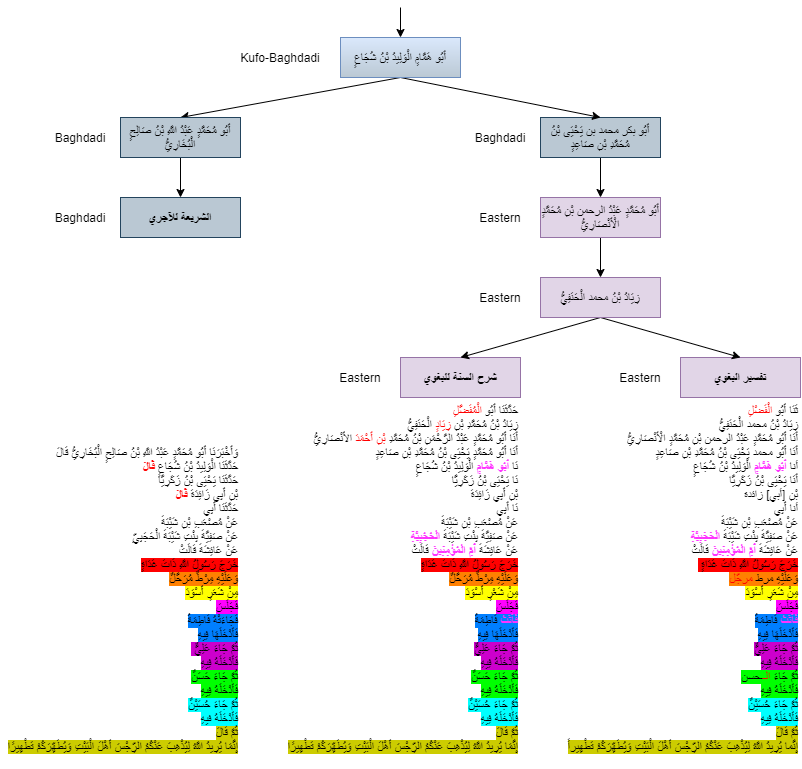

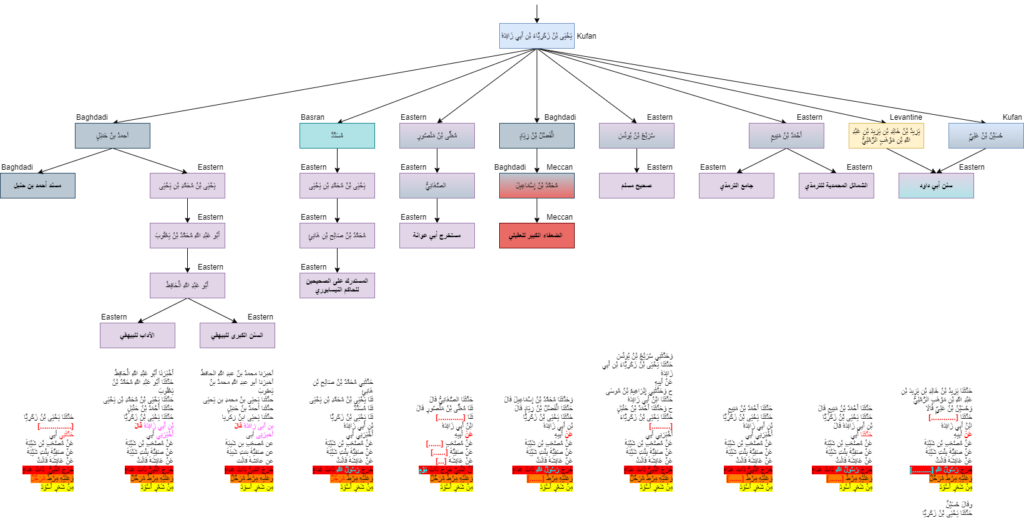

There are several putative common sources (“partial common links” or PCLs) that appear in the isnads of the different versions of this hadith,[2] with all versions ultimately converging on a single source (a “common link” or CL).

By carefully comparing these mutual clusters of ascriptions to these respective PCLs, distinctive sub-traditions can often be discerned, which is consistent with the particular wordings or redactions of the PCLs’ having been (to at least some extent) preserved.

Thus, the ascriptions to the Kufan tradent ʿUṯmān b. ʾabī Šaybah (d. 239/853) are more similar to each other than to other versions of the hadith (sharing certain distinctive wordings), which is consistent with his being a genuine PCL.

The same goes for the ascriptions to the Kufo-Baghdadian tradent al-Walīd b. Šujāʿ (d. 243/857), which largely share the same elemental sequence.

The same goes for the ascriptions to the Kufan tradent Muḥammad b. Bišr (d. 203/818-819), which largely share the same elemental sequence.

The same goes for most of the ascriptions to the Kufan tradent Yaḥyá b. Zakariyyāʾ b. ʾabī Zāʾidah (d. 183-184/799-800), which are abridged in the same way, comprising far fewer elements.

However, it would also seem that Yaḥyá transmitted an unabridged version of the hadith. The distinctiveness of this cluster is not strong, but still, most of the relevant ascriptions to Yaḥyá have “Ḥasan” and “Ḥusayn”, where those to others have “al-Ḥasan” and “al-Ḥusayn”.

When all of these resulting PCL redactions are then collated, alongside a remaining SS report, they are certainly more alike than any of the broadly similar Hadith material (i.e., on the cloak and the Prophet’s family and/or Q. 33:33).

The ultimate common source for this distinctive tradition is the Kufan tradent Zakariyyāʾ b. ʾabī Zāʾidah (d. 149/766-767), who is thus probably a genuine CL, to whom the following ur-redaction can be attributed:

Muṣʿab b. Šaybah related to us, from Ṣafiyyah bt. Šaybah, from ʿĀʾišah, who said: “The Prophet departed one morning wearing a black camel-hair cloak; then [al-]Ḥasan came and he placed it on him; then [al-]Ḥusayn came and he placed it on him; then Fāṭimah came and he placed it on her; then ʿAlī came and he placed it on him; then he said: “God only wants to remove any uncleanness from you, the People of the House, and to thoroughly purify you [Q. 33:33].””

Absent parallel transmissions, it is impossible to reach back any farther, at least using an ICMA. Still, a form-critical analysis may yield further insights, if this tradition can be compared with related material.

If we turn instead to traditional Sunnī Hadith scholarship, there are some points of interest regarding this hadith. To begin with, four versions of this hadith can be found in the Sunnī Hadith canon—namely, the Ṣaḥīḥ of Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 261/875) [here and here], the Sunan of ʾAbū Dāwūd Sulaymān (d. 275/889) [here], and the Jāmiʿ of ʾAbū ʿĪsá al-Tirmiḏī (d. 279/892) [here].

Moreover, concerning the version recorded in his collection, al-Tirmiḏī stated: “This is a sound (ṣaḥīḥ), isolated (ḡarīb), good (ḥasan) hadith.”[3] Ostensibly, al-Tirmiḏī acknowledged that the hadith only derives from a “single strand” isnad, but one that is still reliable.

The Khurasanian Hadith scholar al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī (d. 405/1014) also recorded versions of this hadith. On one, he said: “This is a sound (ṣaḥīḥ) hadith according to the criterion of the two shaykhs [i.e., al-Buḵārī and Muslim], although it was not cited by both of them.”[4] Concerning another, al-Ḥākim stated: “This hadith is sound (ṣaḥīḥ) in terms of the isnad, although it was not cited by both of them [i.e., i.e., al-Buḵārī and Muslim].”[5]

Finally, the Khurasanian Hadith scholar al-Baḡawī (d. 516/1122) also recorded several versions of the hadith. Concerning two of them, he said: “This is a sound (ṣaḥīḥ) hadith. Muslim cited it…”[6]

Overall, then, it seems like traditional Sunnī Hadith scholarship deemed this hadith to be sound, despite its ostensibly Šīʿī content or potential Šīʿī utility. (This is not an isolated instance, exemplifying the diverse ideological provenance of the “Sunnī” Hadith corpus.[7])

That said, the CL for this hadith, Zakariyyāʾ, actually had a mixed reputation amongst the proto-Sunnī Hadith critics: Ibn Ḥanbal said he was “reliable” (ṯiqah); ʾAbū Zurʿah said that he was “pious/good” (ṣuwayliḥ) [i.e., mediocre]; and ʾAbū Ḥātim said that he was “lax in Hadith (layyin al-ḥadīṯ)” and that “he used to deceive” (yudallisu), presumably meaning that he would interpolate or tamper with isnads (i.e., what is usually meant by tadlīs).[8]

Likewise, Zakariyyāʾ’s immediate cited source, the Meccan tradent Muṣʿab b. Šaybah (fl. early 8th C. CE?), had a mixed reputation: one the one hand, al-ʿIjlī and Ibn Maʿīn said that he was “reliable” (ṯiqah); but on the other hand, ʾAbū Ḥātim said that “he was not strong” (laysa bi-qawiyy), and Ibn Ḥanbal said that “he transmitted rejected hadiths” (rawá ʾaḥādīṯ manākīr).[9]

Thus, whilst later Sunnī Hadith scholars judged the hadith to be sound, early Hadith critics were divided regarding the reliability of its transmitters.

For a final historical-critical point of interest, the CL Zakariyyāʾ was Kufan—and, as it happens, Kufah was the centre of Šīʿism at that time. Moreover, Zakariyyāʾ was a member of the Banū Hamdān, who were disproportionately supporters of ʿAlī.[10] This is unlikely to be a coincidence: it is hard to escape the suspicion that the hadith originated in the early Šīʿī milieu of Kufah, which calls into question Zakariyyāʾ’s ascription thereof via a Meccan SS unto ʿĀʾišah in Madinah. Of course, at this stage, this is speculative; a further form-critical and geographical analysis of all of the related traditions on this topic is required for more confident results.

In sum, this tradition about the Prophet’s mantle and family can be traced back to the early 8th-Century Kufan CL Zakariyyāʾ; it was often regarded as ṣaḥīḥ in Sunnī scholarship; but there are mixed judgements on Zakariyyāʾ and his source; and hadith suspiciously matches a Kufan context.

* * *

For the original Twitter thread upon which this article is based, see: https://twitter.com/IslamicOrigins/status/1543941167162728450?s=20

[1] Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj al-Naysābūrī (ed. Naẓar b. Muḥammad al-Fāryābī), Ṣaḥīḥ, 2 vols. in 1 (Riyadh, KSA: Dār Ṭaybah, 2006), p. 1136, # 2424.

[2] For an anthology of some of these versions, see Baššār ʿAwwād Maʿrūf, et al., al-Musnad al-Jāmiʿ, vol. 20 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Jīl, 1993), pp. 331-332, # 17204.

[3] Muḥammad b. ʿĪsá al-Tirmiḏī (ed. ʾIbrāhīm ʿAṭwah ʿIwaḍ), al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, vol. 5 (Cairo, Egypt: Maṭbaʿat Muṣṭafá al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī, 1975), p. 119, # 2813.

[4] Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī (ed. Muṣṭafá ʿAbd al-Qādir ʿAṭā), al-Mustadrak ʿalá al-Ṣaḥīḥayn, vol. 4 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 2002), p. 159, # 739/37.

[5] Ibid., III, p. 208, # 5707/305.

[6] Al-Ḥusayn b. Masʿūd al-Baḡawī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ), Šarḥ al-Sunnah, vol. 12 (Beirut, Lebanon: al-Maktab al-ʾIslāmiyy, 1983), p. 26; ibid., XIV, p. 116.

[7] E.g., Christopher Melchert, ‘Sectaries in the Six Books: Evidence for their Exclusion from the Sunni Community’, The Muslim World, Volume 82, Numbers 3-4 (1992), 287-295.

[8] Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar ʾAʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 6, 2nd ed. (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1982), pp. 202-203.

[9] ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Ḥātim, Kitāb al-Jarḥ wa-al-Taʿdīl, vol. 8 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār ʾIḥyāʾ al-Turāṯ al-ʿArabiyy, 1953), p. 351; ʾAḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿIjlī (ed. ʿAbd al-Muʿṭī Qalʿajī), Taʾrīḵ al-Ṯiqāt (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Bāz, 1984), p. 430.

[10] E.g., Emeri J. van Donzel, Islamic Desk Reference: Compiled from The Encyclopaedia of Islam (Leiden, the Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1994), 127.