The city of Medina in Western Arabia is best known as the sanctuary of the exiled Meccan prophet Muḥammad, were he founded the religious polity that would go on to become both the Arab empire and the religion of Islam. The city was originally called Yaṯrib, but from the time of Muḥammad onward it was commonly referred to as “the Prophet’s city” (madīnat al-nabiyy), “the prophetical city” (al-madīnah al-nabawiyyah), or simply “the city” (al-madīnah), the latter of which gave rise to the English “Medina”. (In order to forestall any confusion, I will henceforth refer to the city via this Anglicised form.)

Thus, as a general rule, any isolated or unqualified reference to “the city” (al-madīnah) refers to Medina, as in the following famous report from al-Zubayr b. Bakkār (Medino-Meccan; d. 256/870):

Yaḥyá b. Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Ṯawbān related to me—he said: “I heard ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Zayd b. ʾAslam [Medinan; d. 182/798-799] say: ‘When the ʿAbd Allāhs—ʿAbd Allāh b. al-ʿAbbās [d. 67-68/686-688], ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Zubayr [d. 73/692], ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar [d. 73-74/691-693], and ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAmr b. al-ʿĀṣ [d. 63-69/682-689]—died, jurisprudence passed to non-Arab converts (al-mawālī) in [nearly] all lands. Thereafter, the jurist of the People of Makkah was ʿAṭāʾ b. ʾabī Rabāḥ [d. 114-117/732-735]; the jurist of the People of Yemen was Ṭāwūs [b. Kaysān; d. 106/725]; the jurist of the People of Kufah was ʾIbrāhīm [b. Yazīd al-Naḵaʿī; d. 96/714]; the jurist of the People of al-Yamāmah was Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr [d. 129-132/747-750]; the jurist of the People of Basrah was al-Ḥasan [b. Yasār; d. 110/728]; the jurist of the People of Syria was Makḥūl [d. 112-118/730-736]; and the jurist of the People of Khurasan was ʿAṭāʾ al-Ḵurāsānī [d. 135/752-753]. [This happened everywhere] except for al-Madīnah, for verily, God assigned it to a Qurašī: the undisputed jurist of the People of al-Madīnah [thereafter] was Saʿīd b. al-Musayyab [d. 93-95/711-714].’”[1]

In this context, “al-Madīnah” (literally, “the city”) clearly means Medina. Of course, such an identification is easier in a case like this, in which “al-Madīnah” is listed alongside Makkah and other early centres of Islamic learning—but even without these others, the meaning would still be clear. For example, an entry in a biographical dictionary starts as follows: “Rabīʿah b. ʾabī ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Farrūḵ; a leading scholar; the muftī of al-Madīnah and the [leading] scholar of the time; [his teknonym was] ʾAbū ʿUṯmān.”[2] Absent some confounding factor, al-Madīnah (i.e., “the city”) means Medina in a case like this.

The nisbah or relative adjective derived from Medina is madanī, which is to say: anybody bearing the epithet of “al-Madanī”, or who is otherwise described as “Madanī”, should be presumed to be someone who lived in Medina. For example, if we turn to a biographical dictionary and look up the entry on the narrator of the report cited above, we discover the following: “ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Zayd b. ʾAslam al-ʿUmarī al-Madanī.”[3] This immediately tells us that ʿAbd al-Raḥmān was born in, and/or lived in, Medina.

So far, so good: what I have described up to this point is elementary knowledge for anyone who works with Hadith. However, there is another nisbah that is not as straightforward: madīnī. The most famous figure bearing such an epithet is undoubtedly the early Basran Hadith scholar ʾAbū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Madīnī (d. 234/849), who is often known simply as Ibn al-Madīnī. For a long time, I simply assumed that Madīnī is a synonym for Madanī, an assumption that seems to be borne out in the case just cited: as it turns out, Ibn al-Madīnī originated, or had family roots, in Medina.[4] For another example, consider ʾAbū Maʿšar Najīḥ al-Sindī, who is called “al-Madīnī” in some sources and “al-Madanī” in others: in his case, the synonymity is clear;[5] and, as it turns out, he lived for some time in Medina.[6]

There was always something that bothered me about this nisbah, however: in retrospect, I think that I must have encountered some “Madīnī” tradents who did not otherwise come across as Medinan—for example, “Madīnī” tradents whose masters and students alike were not Medinan. However, it was only recently that this suspicion came to a head, in the course of some research for my previous blog article relating to the history of Isfahan.

In order to test whether a special connection existed between the cities of Basrah and Isfahan in the early Arab empire, I used the Shamela database to conduct a keyword search of ʾAbū al-Šayḵ al-ʾAṣbahānī’s Ṭabaqāt al-Muḥaddiṯīn bi-ʾAṣbahān wa-al-Wāridīn ʿalay-hā, a biographical dictionary of the Hadith scholars of Isfahan. In particular, I searched for (1) individual nisbahs indicating the regional provenance of scholars who visited Isfahan and disseminated Hadith there (i.e., every instance of a scholar with an entry in the book whose regional origin is indicated); and (2) collective nisbahs indicating the regional provenance of the teachers of Isfahani scholars (i.e., every instance of a scholar with an entry in the book whose teachers are referred to by a collective regional nisbah). I focused my search on the five leading centres of early Islamic learning, searching for Meccans, Medinans, Syrians, Kufans, and Basrans; although I also searched for Baghdadis, given Baghdad’s meteoric rise in the early Abbasid period. The results were exactly what I expected: Basrans predominate in general; Baghdadis rival Basrans after the founding of Baghdad during the early Abbasid period; Kufans are well represented; and Syrians, Medinans, and Meccans have little to no representation. This was completely predictable: Isfahan is located close to Iraq; Isfahan was conquered by an Iraqi—or, specifically, a Basran—army in the first place; and the governor of Basrah also ruled Isfahan from the time of its conquest through to the Umayyad period.[7]

There was however one oddity in all of this: when I searched for “Madīnī” tradents and the phrase “from the People of Medina” (min ʾahl al-madīnah), a surprisingly large number of hits was returned: in many cases, ʾAbū al-Šayḵ would describe a tradent as “Madīnī”, or list their epithet as “al-Madīnī”, or otherwise describe them as hailing “from amongst the people of al-madīnah”. Immediately, something seemed off about all of this: could there really be so many Medinans represented amongst the scholars of Isfahan, so far from the Hijaz?

My suspicions only grew as I encountered examples such as Dirham b. Muẓāhir and ʿAbd al-Wāriṯ b. al-Firdaws,[8] both of whom were described as hailing “from amongst the people of al-madīnah”: could such Persian-coded individuals really have hailed from Medina? One could certainly imagine a scenario in which a Persian slave was taken to distant Medina, only to be freed and to return home later on, now bringing some hadiths with them. However, when a biographical dictionary about the scholars of a Persian city lists someone with a Persian-coded name and/or with a parent with a Persian-coded name, the obvious inference would be that the person in question was simply a local, i.e., someone who grew up and lived in Isfahan or the surrounding area.

The straw that broke the [Bactrian] camel’s back was the following entry in ʾAbū al-Šayḵ’s biographical dictionary: “ʿUmar [sic] b. Šihāb b. Ṭāriq al-Madīnī; he would transmit from Hilāl al-Wazzān and others, and he devoted himself to studying the jurisprudence of the legal school of the Kufans (wa-kāna yatafaqqahu ʿalá maḏhab al-kūfiyyīn).”[9] It is not impossible that a Medinan would abandon the legal tradition of his native Medina (i.e., the proto-Mālikī school) in favour of the legal tradition of Kufah (i.e., the proto-Ḥanafī school) and then end up in Isfahan, but it does seem surprising. Or, to put it another way: the far more expected explanation for a scholar listed in a book of Isfahani scholars as a devotee of the “Kufan” or Ḥanafī legal tradition is that the scholar is simply yet another local who embraced the Ḥanafī school that was emanating out of Baghdad and into the Persianate East.[10]

Clearly, my assumption that “Madīnī” was a synonym for “Madanī”, and that “of the people of al-madīnah” referred to Medina, was wrong, at least in this context. I initially attempted to search for discussions of the meaning of “Madīnī” online, but the initial results—in both English and Arabic—were overwhelmed by general discussions of the famous Ibn al-Madīnī. I thus reached out to several Hadith-oriented colleagues, including Jonathan Brown, who knew exactly where to look to find an answer to this puzzle: ʿIzz al-Dīn Ibn al-ʾAṯīr al-Jazarī (Mawṣilī; d. 630/1233)’s al-Lubāb fī Tahḏīb al-ʾAnsāb, a dictionary of nisbahs. Therein, Brown discovered—and directed me to—the following entry:

al-Madīnī.[Spelled] with a fatḥ [on] the mīm; and a kasr [on] the dāl; and a sukūn [on] the yāʾ, under which there are two dots; and at the end there is a nūn [prior to the final yāʾ].

This nisbah [refers] to a number of cities.

[1] The first is the Messenger of God (ﷺ)’s city [i.e., Medina]: the most common nisbah therefor is madanī, [whereas madīnī] refers thereto [whilst still] showing the [middle] yāʾ. Amongst those who are referred to like this is ʾAbū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh b.[11] Jaʿfar b. Najīḥ al-Saʿdī, known as Ibn al-Madīnī: he originated in Medina [and] settled in Basrah; he transmitted from [Sufyān] b. ʿUyaynah, Ḥammād b. Zayd, and others; al-Buḵārī and other leading scholars transmitted from him; he was [one] of the most knowledgeable people of his time regarding the subtle defects [that occur in the transmission of] the Hadith of the Messenger of God (ﷺ); he died when two days remained from [the month of] Ḏū al-Qaʿdah, in the year 234 [i.e., 849 CE], and was buried in the military district [of Sāmarrāʾ]; and his birth occurred in the year 162 [i.e., 778-779 CE].

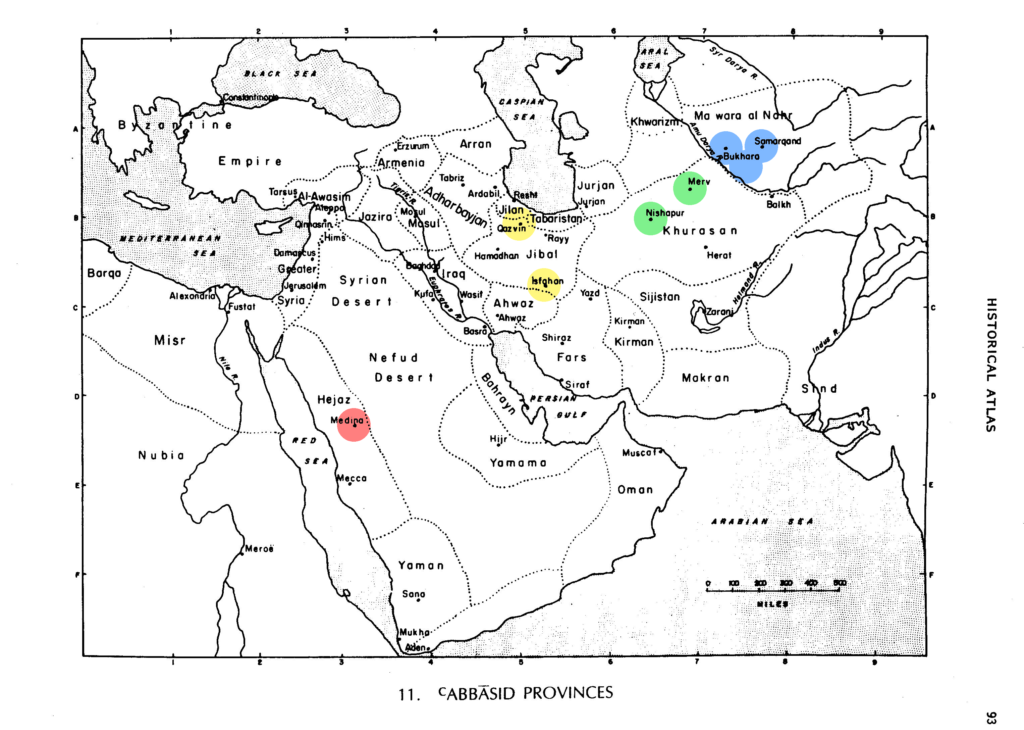

[2] The second is the inner city of Marw [in Khurasan]. Many [instances of “Madīnī”] refer thereto. Amongst them is ʾAbū Rūḥ Ḥātim b. Yūsuf al-Madīnī al-ʿĀbid al-Marwazī; he transmitted from [ʿAbd Allāh] b. al-Mubārak; and Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad b. Ḥakīm transmitted from him.

[3] The third [usage refers] to the city of Naysābūr [in Khurasan], which the [early Arab] military[12] was not able to plunder. [One of those] therefrom is ʾAbū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad b. al-Ḥusayn b. ʿUmārah al-Madīnī: he heard from ʾIsḥāq b. Rāhwayh, Muḥammad b. Nāfiʿ, and others.

[4] The fourth [usage refers] to the city of Isfahan [in central Persia], which is [also known as] Gey. A large number [of people have nisbahs] referring thereto. Amongst them is ʾAbū Jaʿfar ʾAḥmad b. Mahdī b. Rustam al-Madīnī al-ʾAṣbahānī: he wrote down [Hadith] from ʾAbū al-Yamān in Syria, and from ʾAbū Nuʿaym and others in Iraq; he was reliable.

[5] The fifth [usage refers] to the city of al-Mubārak in Qazwīn [in northern Persia]. [One of those] therefrom is ʾAbū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf b. Ḥamdān al-Madīnī al-Qazwīnī; he heard Muḥammad b. Ḥumayd al-Rāzī and others; and ʿAlī b. Muḥammad b. Mahdawayh al-Qazwīnī transmitted from him; and he died in 303 [i.e., 915-916 CE].

[6] The sixth [usage refers] to the city of Buḵārá [in Transoxiana]. A large number of the leading scholars hailed therefrom, including ʾAbū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad b. ʾabī Bakr b. ʿUṯmān al-Madīnī al-Bazdawī; [he was] a pious, God-fearing shaykh; he was the companion of al-Zāhid al-Ṣaffār; he heard Hadith from ʾAbū Muḥammad al-Zuhrī, ʾAbū Bakr al-Nasafī, and others.

[7] The seventh is the city of Samarqand [in Transoxiana]. [One of those] therefrom is ʾAbū Bakr ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʾAḥmad al-Madīnī al-Samarqandī; he would transmit from ʾAbū ʿUmar al-Ḥawḍī; and Muḥammad b. ʿĪsá al-Ḡazzāl transmitted from him.

[8] The eighth is the city of Nasaf [in Transoxiana]. A large number [of people with the nisbah al-Madīnī hail] therefrom, one of whom is ʾAbū Muḥammad Ḥāmid b. Šākir b. Sawrah b. Wanūsān al-Warrāq al-Madīnī al-Nasafī: [he was] reliable [and] venerable; he transmitted [the Kitāb] al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ from Muḥammad b. ʾIsmāʿīl al-Buḵārī, and he transmitted from ʾAbū ʿĪsá al-Tirmiḏī and others; ʾAbū Yaʿlá ʿAbd al-Muʾmin b. Ḵalaf al-Nasafī heard the Kitāb [al-Jāmiʿ] al-Ṣaḥīḥ from him; and he died in [the month of] Ḏū al-Qaʿdah, in the year 311 [i.e., 924 CE].[13]

My suspicions were thus confirmed: in ʾAbū al-Šayḵ’s biographical dictionary of Isfahan, “Madīnī” clearly means “[someone] of the city [of Isfahan]”, whilst min ʾahl al-madīnah clearly means “[someone] from amongst the people of the city [of Isfahan].”

When I mentioned all of this to a senior colleague whose research focuses heavily upon the regionality of Hadith transmitters (and who, like Batman, prefers to remain in the shadows), he happily informed me not just that he was already aware of the polysemy of the nisbah “Madīnī”, but that he had already examined and identified the specific regional provenance of more than 200 “Madīnī” tradents cited across the Hadith corpus, carefully distinguishing the Medinans, Isfahanis, and others from each other. As per usual, he was two steps ahead of me…

In short, contemporary Hadith researchers should be aware of the tricksy nisbah “Madīnī”, which sometimes means “Medinan”, but often means “Isfahani” or even something else; and of the ready availability of traditional sources like Ibn al-ʾAṯīr’s Lubāb, which can shed light on such matters. In other words, even for those of us who reject the methods and conclusions of traditional Hadith scholarship in relation to the accrediting of tradents and the authentication of hadiths, such scholarship remains a treasure trove of useful data that should not be overlooked. As always, we stand on the shoulders of giants…

* * *

I owe special thanks to Jonathan Brown, Khodadad Rezakhani, and Raashid Goyal, for their assistance in various aspects of this research.

I also owe thanks to N, al-Baraa El-Hag, A, CJ Canton, H, Mehrab, abcshake, A, A, Anthony Wagner, Inquisitive Mind, L, Marijn van Putten, Q, and Y, for their generous support over on Patreon.

Anyone else wishing to financially support this blog can do so over on my Patreon (here) or via my PayPal (here).

[1] ʾAḥmad b. ʾabī Ḵayṯamah Zuhayr b. Ḥarb (ed. Ṣalāḥ b. Fatḥī Halal), al-Taʾrīḵ al-Kabīr al-Maʿrūf bi-Taʾrīḵ Ibn ʾabī Ḵayṯamah, vol. 2 (Cairo, Egypt: al-Fārūq al-Ḥadīṯiyyah, 2004), p. 104; Muḥammad b. ʾIsḥāq al-Fākihī (ed. ʿAbd al-Malik b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Duhayš), ʾAḵbār Makkah fī Qadīm al-Dahr wa-Ḥadīṯi-hi, vol. 2, 2nd ed. (Makkah, KSA: Dār Ḵaḍir, 1994), pp. 342-343; ʿAlī b. al-Ḥasan b. ʿAsākir (ed. ʿUmar b. Ḡaramah al-ʿAmrawī), Taʾrīḵ Madīnat Dimašq, vol. 60 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Fikr, 1997), p. 214. For more on this report and its broader subject, see Harald Motzki, “The Role of Non-Arab Converts in the Development of Early Islamic Law”, Islamic Law and Society, Vol. 6, No. 3 (1999), pp. 293-317.

[2] Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar ʾAʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 6, 2nd ed. (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1982), p. 89.

[3] Ibid., VIII, p. 349.

[4] See below.

[5] E.g., ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAdī al-Qaṭṭān (ed. Māzin b. Muḥammad al-Sarsāwī), al-Kāmil fī Ḍuʿafāʾ al-Rijāl, vol. 10 (Riyadh, KSA: Maktabat al-Rušd, 2013), pp. 216 ff.

[6] E.g., Ḏahabī, Siyar, VII, p. 439.

[7] For all of this, see my recent blog article, nn. 99-100.

[8] ʾAbū al-Šayḵ ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad al-ʾAṣbahānī (ed. ʿAbd al-Ḡafūr ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq Ḥusayn al-Balūšī), Ṭabaqāt al-Muḥaddiṯīn bi-ʾAṣbahān wa-al-Wāridīn ʿalay-hā, vol. 2 (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1992), pp. 189, 374.

[9] Ibid., III, p. 211.

[10] Whilst the Ḥanafī school has its roots in the legal tradition (i.e., the customs, authorities, and reports) of early Kufah, the Ḥanafī school as such coalesced in Baghdad, according to Christopher Melchert, “How Ḥanafism came to originate in Kufa and Traditionalism in Medina”, Islamic Law and Society, Vol. 6, No. 3 (1999), pp. 318-347, and id., “The Early Ḥanafiyya and Kufa”, Journal of Abbasid Studies, Vol. 1 (2014) pp. 23-45.

[11] Here emending min to bn.

[12] Here emending al-ḡz to either al-ḡazwah or al-ḡazāh. I owe thanks to Raashid Goyal for this suggestion.

[13] ʿIzz al-Dīn Ibn al-ʾAṯīr al-Jazarī, al-Lubāb fī Tahḏīb al-ʾAnsāb, vol. 3 (Baghdad, Iraq: Maktabat al-Muṯanná, n. d.), pp. 184-185.