In his al-ʾItqān fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾân, the famous Egyptian Sunnī Hadith scholar al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) mentioned the following hadith:

Al-Ṭabarānī cited [a hadith] in [his al-Muʿjam] al-Kabīr, from the transmission-path of al-Walīd b. Muslim, from ʿUfayr b. Maʿdān, from Ibn ʿĀmir, from ʾAbū ʾUmāmah, who said: “The Messenger of God said: “The Quran was revealed in three places: Makkah, Madinah, and the Levant (al-šām).”

Al-Walīd said: “Meaning: Jerusalem (bayt al-maqdis).”

And Shaykh ʿImād al-Dīn Ibn Kaṯīr said: “Rather, its interpretation [as a reference] to Tabūk is better [i.e., more plausible] (ʾaḥsan).”[1]

The isnads of all versions of this hadith[2] converge upon al-Walīd b. Muslim (Syrian; d. 195/810), from ʿUfayr b. Maʿdān (Syrian; d. c. 166/782-783), from Sulaym b. ʿĀmir (Syrian; d. 130/747-748), from ʾAbū ʾUmāmah (Hijazo-Syrian; d. 81/700-701 or 86/705), from the Prophet. The reputations of some of these tradents were mixed:

- According to the Syrian Hadith scholar al-Ḏahabī (d. 748/1348), al-Walīd b. Muslim “was amongst the [great] receptacles of knowledge (min ʾawʿiyat al-ʿilm); a reliable tradent (ṯiqah); [and a good] memoriser (ḥāfiẓ). However, he was corrupted [by his engaging in certain isnad-related forms of] deception (radīʾ al-tadlīs); thus, [it is only] when he [explicitly] says, “he related to me” [that] he [can be treated as] a [trustworthy] authority (ḥujjah).”[3]

- According to Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn (d. 233/848), ʿUfayr b. Maʿdān was “nothing (lā šayʾ)”; according to Duḥaym (d. 245/859), he was “nothing (laysa bi-šayʾ)”; and according to ʾAbū Ḥātim al-Rāzī (d. 277/890), “he was weak in Hadith (ḍaʿīf al-ḥadīṯ); he was prolific in transmitting (yukṯir al-riwāyah) rejected hadiths without [any true] source (bi-al-manākīr mā lā ʾaṣl la-hu) from Sulaym b. ʿĀmir, from ʾAbū ʾUmāmah, from the Prophet; his transmission is not to be bothered with (lā yuštaḡalu bi-riwāyati-hi).”[4]

- According to al-ʿIjlī (d. 261/874-875), Sulaym b. ʿĀmir was “reliable (ṯiqah)”; but according to ʾAbū Ḥātim, he was merely “unproblematic (lā baʾs bi-hi)” (a lacklustre status).[5]

However, despite al-Walīd and Sulaym’s mixed reputations, and ʿUfayr’s extremely negative reputation (including specifically in regards to his transmissions from Sulaym, from ʾAbū ʾUmāmah, from the Prophet), the Persian Hadith critic al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī (d. 405/1014) judged this hadith (or at least the version that he cited) to be “sound” (ṣaḥīḥ).[6]

The interpretation of this hadith is debated, as we have already seen. On the one hand, its Syrian transmitter al-Walīd b. Muslim reportedly clarified that ‘the Levant’ here specifically “means Jerusalem (bayt al-maqdis).”[7] According to the later Syrian Sunnī scholar Ibn Kaṯīr (d. 774/1373), however, this is wrong: “The interpretation of “the Levant” (al-šām) [as a reference to] Tabūk is better [i.e., more plausible] (ʾaḥsan) than what al-Walīd said (“it is Jerusalem”). God knows best.”[8]

Pace Ibn Kaṯīr, this hadith is clearly referring to the Levant proper (i.e., Syro-Palestine) and Jerusalem in particular, for several reasons:

- The default or primary meaning of “the Levant” (al-šām) is Syro-Palestine, centred on cities like Ḥimṣ, Beirut, Damascus, Buṣrá, Caesarea, Jerusalem, and Gaza.

- Tabūk was traditionally regarded as located in the northern section of the West-Arabian region of al-Ḥijāz,[9] not as part of al-Šām or the Levant; this would straightforwardly remove Tabūk from consideration.

- The hadith’s disseminator al-Walīd, who is much earlier than Ibn Kaṯīr (and thus closer to hadith’s original milieu), directly contradicts him.

- The hadith (per its Syrian isnad) evidently originated in the Levant proper (i.e., Syro-Palestine), which makes it much more likely that “the Levant” (al-Šām) refers to the Levant proper (i.e., Syro-Palestine), assuming a link between the hadith’s content and transmitters.

- The hadith perfectly fits the broader Levantine and Umayyad tendency of creating regional propaganda (faḍāʾil), along with the Jerusalemite tendency in early Islamic sacred geography (that competed with the Hijaz).[10]

- The symbology or symmetry of the hadith works much better if it describes the three holiest locations of early Islam (Makkah + Madinah + Jerusalem), not two of them and then a random third location.

I can only assume that Ibn Kaṯīr was trying to reconcile this hadith with the traditional biography and geography of the Prophet more broadly, which place 99% of his prophetical career in the Hijaz.

Interestingly, Stephen Shoemaker goes in exactly the opposite direction in his recent book Creating the Qur’an, citing this hadith as some kind of Islamic half-memory of an otherwise-suppressed Syro-Palestinian milieu that produced part of the Quran:

Al-Suyūṭī is admittedly a rather late author, who wrote in only the fifteenth century, and yet, based on what we have seen in this book, we must regard this tradition, which he brings on the authority of al-Ṭabarāni, as ṣaḥīḥ. Although the Qur’an seemingly has deep roots in the preaching of Muhammad to his earliest followers in Mecca and Medina, the text that we have today was composed no less, it would seem, in Syria—that is, in al-Shām or Syro-Palestine—as well as in Mesopotamia. Numerous reasons and a vast array of evidence lead us unmistakably to this conclusion. The bewildering confusion and complexity of the early Islamic memory of the Qur’an’s formation, as we saw in the first two chapters, only reaches some level of clarity once we recognize ʿAbd al-Malik as the primary agent responsible for producing and enforcing the canonical textus receptus of the Qur’an.[11]

There is something odd about Shoemaker’s citation, however: rather than citing al-Suyūṭī’s cited source for this hadith (al-Ṭabarānī), he instead just cites al-Suyūṭī and argues that al-Suyūṭī’s citation is reliable. That well may be, but al-Ṭabarānī’s al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr is extant and available. Why jump through such an unnecessary hoop? Why not just bypass al-Suyūṭī altogether and cite al-Ṭabarānī directly, a much earlier source? This is extremely odd.

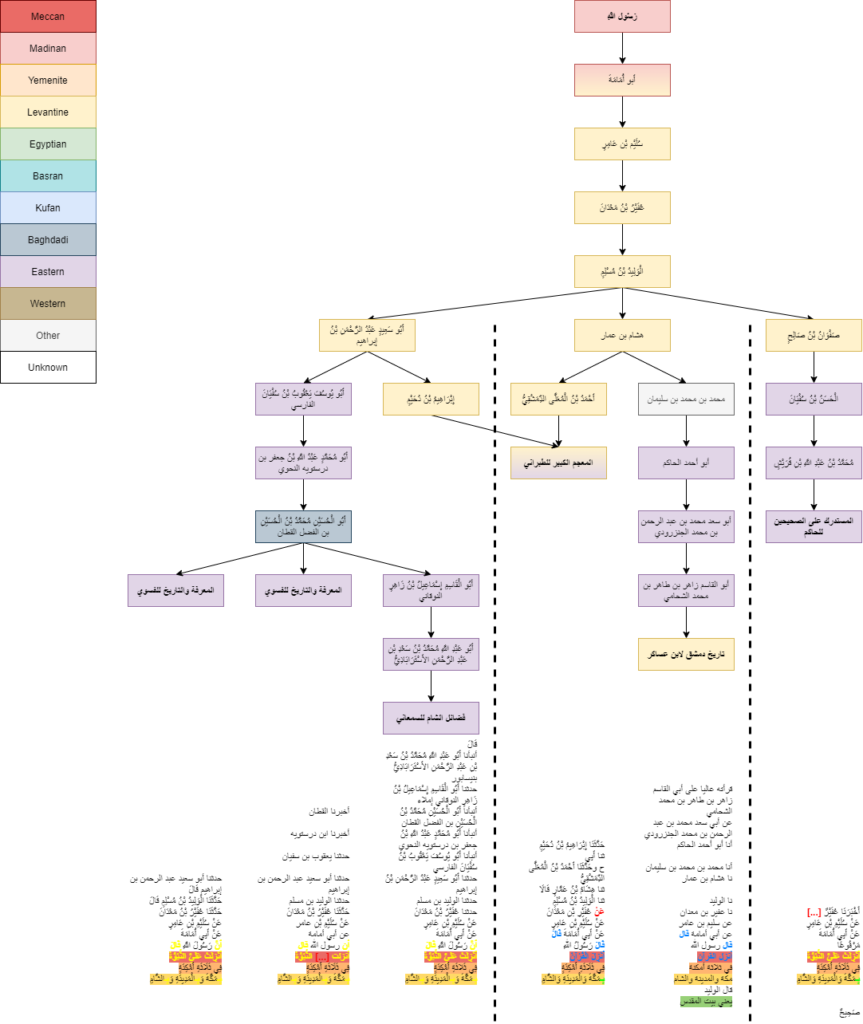

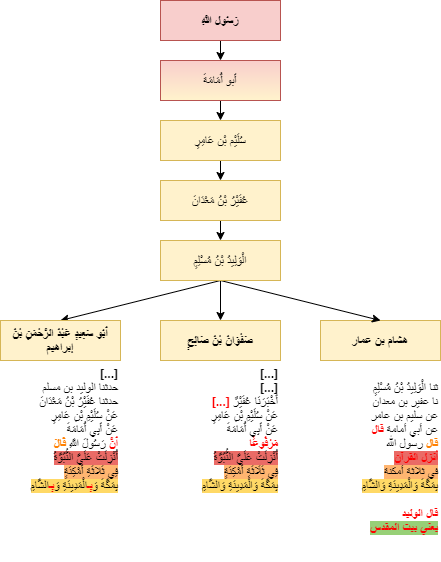

There is also no need to stop at al-Ṭabarānī: by collating and comparing other transmissions of this hadith, three different Syrian PCLs with their own distinctive redactions can be discerned, all reflecting and citing the ur-redaction of the Syrian CL al-Walīd:

In other words, by applying an isnad-cum-matn analysis, the following ur-redaction can be reconstructed back to the CL al-Walīd (d. 195/810):

ʿUfayr b. Maʿdān related to us, from Sulaym b. ʿĀmir, from ʾAbū ʾUmāmah, that the Messenger of God said: “Prophethood was bestowed upon me in three places (ʾunzilat ʿalayya al-nubuwwah fī ṯalāṯat ʾamkinah): in Makkah, Madinah, and the Levant (al-šām).”

This immediately reveals another weakness in Shoemaker’s approach: the version he cites (“The Qur’an was revealed in three places: Mecca, Medina, and Syria”) is actually a secondary reformulation by the Syrian PCL Hišām b. ʿAmmār (d. 245/859), who changed the CL’s original formulation. Whereas al-Walīd (as preserved by the other students) had the Prophet say, “Prophethood was bestowed upon me in three places”, Hišām instead made the Prophet say, “The Quran was revealed in three places”.

These statements are not identical: the former could include the latter, but also other things, like non-Quranic revelation, teaching, preaching, and other events and activities—including, most obviously, the Night Journey, which allegedly took place in Jerusalem. Shoemaker’s argument thus rests on a falsely-specific rewording, a PCL alteration of a CL’s original wording that does not actually state that the Quran was partially revealed in the Levant, but is instead more likely a reference to the Night Journey.

The idea that this hadith (in any version) reflects a genuine historical memory of the Syro-Palestinian provenance of the Quran seems extremely implausible, and I am surprised that Shoemaker of all people would conclude such. Shoemaker is quite aware of the pro-Umayyad, pro-Levantine, and pro-Jerusalemite tendencies that were active (alongside many others, of course) in early Islam and early Hadith: he documented them in The Death of a Prophet, ch. 4.

Surely it is simpler to suppose that this is just one of the many faḍāʾil reports produced by these tendencies, an early attempt to retain the sacred importance of Jerusalem (alongside Makkah and Madinah)? Put differently, 8th-Century Syria is a sufficient “Sitz im Leben” for this hadith—it would be totally gratuitous to suppose that it reflects an even earlier hypothetical proto-Islamic milieu.

Of course, al-Walīd (d. 195/810) was not operating in the Marwanid Syria (the most obvious time and place for the emergence of this hadith), but rather, early Abbasid Syria. It is thus possible that this hadith is a relatively late pro-Levantine creation (for example, pushing back against the post-Umayyad decline in the Levant’s pre-eminence), although equally, we may simply have an instance of an earlier (Marwanid-era) creation that only survives via the formulation and dissemination of a later CL.[12]

In sum, this hadith was disseminated in Syria by the CL al-Walīd b. Muslim (d. 195/810), citing a Syrian SS back to the Prophet; the original version spoke of Prophethood, not the Quran specifically; and it probably reflects the ideological interests of Marwanid Syria, although it could be of even later Syrian provenance. Pace Shoemaker, this hadith cannot be reasonably interpreted as some kind of Islamic fossil-memory of a hypothetical Syro-Palestinian milieu for the Quran.

* * *

For the original Twitter thread upon which this article is based, see: https://twitter.com/IslamicOrigins/status/1564646371373813763?s=20

[1] ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Bakr al-Suyūṭī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ) al-ʾItqān fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾân (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 2008), p. 32.

[2] Recorded in: al-Ṭabarānī’s al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr; the Mustadrak of al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī; the Maʿrifah of al-Fasawī; the Taʾrīḵ Dimašq of Ibn ʿAsākir; and the Faḍāʾil al-Šām of al-Samʿānī.

[3] Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar ʾAʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 9, 2nd ed. (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1982), p. 212.

[4] ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Ḥātim, Kitāb al-Jarḥ wa-al-Taʿdīl, vol. 7 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār ʾIḥyāʾ al-Turāṯ al-ʿArabiyy, 1953), p. 36, # 195.

[5] Ḏahabī (ed. ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar, V, p. 185.

[6] Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī (ed. Muṣṭafá ʿAbd al-Qādir ʿAṭā), al-Mustadrak ʿalá al-Ṣaḥīḥayn, vol. 4 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 2002), p. 555.

[7] ʿAlī b. al-Ḥasan b. ʿAsākir (ed. ʿUmar b. Ḡaramah al-ʿAmrawī), Taʾrīḵ Madīnat Dimašq, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Fikr, 1995), p. 165.

[8] ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʿUmar b. Kaṯīr (ed. Sāmī b. Muḥammad al-Salāmah), Tafsīr al-Qurʾân al-ʿAẓīm, vol. 5, 3rd ed. (Riyadh, KSA: Dār Ṭaybah, 1999), p. 101.

[9] This should be totally uncontroversial, but see, for example, ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Bakrī, Muʿjam mā istaʿjama min ʾAsmāʾ al-Bilād wa-al-Mawāḍiʿ, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: ʿAlam al-Kutub, n. d.), p. 12: “The edge of al-Šām is that which is beyond Tabūk, and Tabūk is [part] of al-Ḥijāz.”

[10] E.g., Ignáz Goldziher (ed. Samuel M. Stern and trans. Christa R. Barber & Samuel M. Stern), Muslim Studies, Volume 2 (Albany, USA: State University Press of New York, 1971 [originally published in 1890]), 44 ff.; Patricia Crone, ‘The First-Century Concept of Hiǧra’, Arabica, Tome 41 (1994), 352-387; Michael Lecker, ‘Biographical Notes on Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī’, Journal of Semitic Studies, Volume 41, Number 1 (1996), 22 ff.; Stephen J. Shoemaker, The Death of a Prophet: The End of Muhammad’s Life and the Beginnings of Islam (Philadelphia, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), ch. 4, and the references cited therein (such as Meir Kister, Shelomo Goitein, Moshe Sharon, and Amikam Elad).

[11] Stephen J. Shoemaker, Creating the Qur’an: A Historical-Critical Study (Oakland, USA: University of California Press, 2022), 259. Emphasis mine.

[12] For a similar concept, see Andreas Görke, ‘Eschatology, History, and the Common Link: A Study in Methodology’, in Herbert Berg (ed.), Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2003), 199.