Abstract:

This blog article revisits a topic covered in one of my previous blog articles: a hadith that appears to have been created in response to the ʿĪsawiyyah, a Jewish messianic movement that erupted in Isfahan during the middle of the 8th Century CE. The present article incorporates some Hadith material that was not covered in the original article and explores this material’s implications for the original article’s core conclusions: (1) that the material is anti-ʿĪsawī; (2) that an iteration of this material was formulated by the Syrian scholar al-ʾAwzāʿī (d. 151-157/768-774) and falsely attributed to earlier sources; and (3) that most other reports embodying this material are products of contamination. Although some modifications are in order, none of these core conclusions are affected by the new evidence, which also points towards a common source undergirding all of the anti-ʿĪsawī material: al-ʾAwzāʿī’s Basran teacher, Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr (d. 129-132/746-750).

Table of Contents:

- Part 1: The Hadith’s Historical Referent

- Part 2: False CLs and the Spread of Isnads

- Part 3: Contamination and the Hadith of Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr

- Part 4: An ICMA of the Hadith of Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr

- Part 5: The Year of Yaḥyá’s Death

- Part 6: The Implications of Yaḥyá as a Genuine CL

- Part 7: al-ʾAwzāʿī and Yaḥyá as Co-Creators

- Part 8: An Alternative Chronology of the ʿĪsawiyyah?

- Part 9: Some More Contaminated Hadiths

- Part 10: Harald Motzki and the Role of CLs

- Summary

- Addendum: Yaḥyá’s Reputation

In October of 2022, I published an article on my blog titled “‘Common Links’ as the Creators of Hadith: A Case Study of a Syrian Prophecy about the Antichrist”. The gist of this article was as follows: in some instances, the “common links” (henceforth, CLs) of hadiths probably created and falsely ascribed their hadiths; the famous Antichrist hadith of the Syrian CL al-ʾAwzāʿī (d. 151-157/768-774) is a probable example of this phenomenon; the hadith likely refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah, a Jewish messianic movement in Isfahan that likely arose 744 ff. CE and rebelled 754 ff. CE; there is also evidence that the ʿĪsawiyyah spread to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s own Syrian milieu; it thus seems probable that this hadith was formulated by al-ʾAwzāʿī in response to an event that occurred in his own lifetime, and that the hadith does not derive from his earlier, cited sources, who died before the event in question. Towards the end of my article, I also consider the possibility that al-ʾAwzāʿī borrowed the basic elements comprising his hadith from his Basran teacher Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr (d. 129-132/746-750), before concluding that it fits more snugly into—and more probably originated in—al-ʾAwzāʿī’s own context.

Several months after the publication of this blog article, in January of 2023, a Twitter user (@MusslimmMan) adduced additional transmissions from Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr, suggesting that Yaḥyá should be regarded as a genuine CL for a hadith about the Antichrist and the Jews of Isfahan.[1] The earliest recorded version of this hadith runs as follows:

Al-Ḥasan b. Mūsá related to us—he said: “Šaybān related to us, from Yaḥyá, from al-Ḥaḍramī b. Lāḥiq, from ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ, from ʿĀʾišah, the Mother of the Believers, who said: ‘The Prophet (ﷺ) entered upon me whilst I was crying, then he said: “Why are you crying?” Then I said: “O Messenger of God, you mentioned the Antichrist…” He said: “Do not cry, for if he emerges whilst I am still alive, I will protect all of you from him; and if I have died [by that point], then verily, your Lord is not one-eyed! And verily the Jews of Isfahan will go out with him, then he will travel until he alights in the vicinity of Madinah, which will have seven gates at that time—and upon each gate there will be two angels. Then the evil ones amongst its people will go out to [join] him, then he will depart until he comes to Lod. Then Jesus, the Son of Mary, will descend and slay him. Thereafter, Jesus will remain on Earth for forty years, or close to forty years, as a just ruler and a fair judge.”’”[2]

In response to this, I initially suggested that these hadiths (i.e., the “Jews of Isfahan” element contained therein) were plausibly contaminated by al-ʾAwzāʿī’s more famous hadith.[3] More recently, however, this suggestion was criticised in a thread by another Twitter user (@KerrDepression), along with various aspects of my original blog article. In particular, this thread argues: that a hadith containing the relevant material can be traced back to Yaḥyá via several different lines of transmission; that my alternative “contamination” explanation therefor is implausible; that Yaḥyá died prior to “the earliest possible date” for the hadith to have been created in response to the ʿĪsawiyyah; that it is “questionable” that the ʿĪsawiyyah spread to Syria during al-ʾAwzāʿī’s lifetime; and that all of this reinforces the fact that al-ʾAwzāʿī did not create his hadith in response to the ʿĪsawiyyah either.[4]

Ever since the question of Yaḥyá’s hadith was raised back in January of 2023, I have been meaning to incorporate it into my analysis of al-ʾAwzāʿī and his hadith. My initial plan was simply to update my original blog article, but since that article has now been specifically criticised, I thought it would be better to leave it up as it is (i.e., to preserve the original argumentation) and make a follow-up article instead. This will allow me not just to cover Yaḥyá’s hadith, but also to unpack a number of broader methodological problems inadvertently raised thereby, including: the problem of false CLs; anachronisms as a means of exposing false CLs; the evidentiary weight of CLs; and the hierarchy of evidence when evaluating the transmission and historical provenance of Hadith.

Part 1: The Hadith’s Historical Referent

To begin with, it is important to reiterate a fundamental point that was already articulated in my original blog article: al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith likely refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah, a messianic Jewish movement that erupted in Isfahan during the 8th Century CE under the leadership of ʾAbū ʿĪsá al-ʾIṣfahānī.[5] The original version of his hadith ran something like this:

ʾIsḥāq b. ʿAbd Allāh {b. ʾabī Ṭalḥah related to me}, from ʾAnas b. Mālik, who said: “The Antichrist (al-dajjāl) will be followed by 70,000 of the Jews of Isfahan, wearing [Persian] garments (ʿalay-him al-ṭayālisah).”[6]

(In the course of his disseminating this hadith, al-ʾAwzāʿī appears to have further raised it all the way back to the Prophet.[7]) This is a good match for the ʿĪsawiyyah: ʾAbū ʿĪsá was—to any outsider, at least—a false messiah or antichrist,[8] which corresponds with the antichrist in the hadith; he was supported by a base of Persian Jews, which corresponds to the Jews wearing certain Persian garments (ṭayālisah) in the hadith; and he and his followers arose and rebelled in Isfahan,[9] which corresponds to the hadith’s specification of Isfahanian Jews. It seems extremely unlikely that such a specific correspondence would arise randomly, and it also seems extremely unlikely that the ʿĪsawiyyah could have been predicted decades prior to their emergence, especially by someone living in far-away Madinah. Consequently, it seems highly likely that this hadith was created—whether through an ex-nihilo fabrication or an ex-materia reworking—as some kind of negative reference to the ʿĪsawiyyah. Similar considerations apply to the hadith attributed to Yaḥyá, not to mention every other hadith containing the distinctive proposition that the Antichrist will be followed by, or will arise amongst, the Jews of Isfahan.

The association of these hadiths with the ʿĪsawiyyah has been criticised in two ways. Firstly, it has been argued that one of these hadiths can be traced back to a CL who transmitted it and died prior to the ʿĪsawiyyah, from which it simply follows that the hadith was not created in response to them. Secondly, it has been argued that al-ʾAwzāʿī—who might have created his hadith after the death of ʾAbū ʿĪsá—would not have created a hadith referring to the ʿĪsawiyyah, since doing so would create problems or contradictions for his own viewpoint. Let us begin with the second criticism first, expressed in the recent Twitter thread as follows:

Also, the idea that followers who migrated after Abu Isa was killed motivated the forgery of this hadith contradicts the hadith being about the Isawiyyah. If Abu Isa was already dead, it would be clear he wasn’t the foretold Al-Dajjal who would be killed by Isa bin Maryam(As). There are also other signs of dajjal in the hadith tradition that one could dig up that don’t align with Abu Isa. If someone created the hadith intending to say “Abu Isa is the dajjal”, it would be tantamount to claiming the dajjal had already emerged. Odd.[10]

There are a number of problems here. Firstly, Israel Friedländer’s observation that some of the ʿĪsawiyyah likely migrated to the Levant after the death of their leader[11] (cited in my original blog article) in no way precludes the movement’s spreading to the Levant prior to his death as well. On the contrary, it is entirely reasonable to suppose that the ʿĪsawiyyah started to spread amongst the Jewish communities of the Levant already during their leader’s heyday (discussed below in Part 7). Secondly, even if it is conceded for the sake of argument that the ʿĪsawiyyah only spread to the Levant after the death of their leader, news of their rebellion must have been circulating contemporaneously in the Jewish-populated Levant (again, discussed below in Part 7), which still leaves a viable context for the hadith’s creation, or in other words: it is perfectly plausible that al-ʾAwzāʿī created and disseminated this hadith whilst ʾAbū ʿĪsá was still alive and rebelling, when the Levant would have been abuzz with word thereof. Thirdly, even if we suppose that al-ʾAwzāʿī only created and disseminated this hadith after ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s death, the theological inconsistency generated thereby (i.e., the contradiction between ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s death before the return of Jesus, on the one hand, and the popular Muslim belief that Jesus would slay the Antichrist, on the other) would only be such if he viewed the matter in a very specific way, which is not at all a given. For example:

- al-ʾAwzāʿī may have identified ʾAbū ʿĪsá as the Antichrist as a way to criticise or insult him and his movement (i.e., as a kind of emotional reaction), without considering—or even caring about—the potential ramifications of such an association.[12]

- al-ʾAwzāʿī may have identified ʾAbū ʿĪsá as the Antichrist merely as a way to criticise or insult him and his movement (i.e., as a rhetorical exaggeration), without intending to identify him as the literal Antichrist.

- al-ʾAwzāʿī may have envisaged ʾAbū ʿĪsá as a lesser antichrist or false prophet, rather than as the archnemesis of Jesus per se.[13]

- al-ʾAwzāʿī may have been inspired by the example of the ʿĪsawiyyah in his own speculations about the End Times, without intending thereby to identify ʾAbū ʿĪsá as the literal Antichrist.

- al-ʾAwzāʿī may have been motivated by the presence of the ʿĪsawiyyah in his region to repackage and propagate an existing anti-ʿĪsawī hadith or statement (i.e., one that was created prior to ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s death) that he himself did not regard as literally anti-ʿĪsawī, but which he was drawn to nevertheless given its resonance with his own milieu.

- al-ʾAwzāʿī may have been responding to the preaching of ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s followers after his death about his return as the Messiah,[14] inverting their prediction with one of his own: that their predicted Messiah was actually the Antichrist. In this respect, the prior death of the real ʾAbū ʿĪsá would be irrelevant, since the real referent here would be the ʾAbū ʿĪsá of subsequent ʿĪsawī eschatology.

And so on, so forth. Most of these kinds of mindsets and interpretations are not based on speculation, but can be found across apocalyptic, messianic, and polemical contexts, past and present: Muslim and Christian polemicists alike throw around the charge of “antichrist” as a way to criticise and condemn their enemies; early Christians persisted in identifying Jesus as the messiah, despite the many inconsistencies between him—for example, his inglorious death—and the hitherto reigning Jewish and Tanakhic conception of the Messiah; some early Muslims continued to believe—and to create and elaborate—predictions that a certain Ibn Ṣayyād was the Antichrist, long after he reportedly died in Madinah during the Battle of al-Ḥarrah (63/683);[15] some early Muslim scholars believed in the existence of lesser antichrists alongside the Antichrist;[16] and so on, so forth.[17]

This is not to say that we know exactly how al-ʾAwzāʿī interpreted the hadith that he created. Rather, the point that it is perfectly plausible that al-ʾAwzāʿī would have created such a hadith after ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s death despite of the problems posed thereby for a certain point of view, which means that the problems posed thereby for a certain point of view simply do not preclude such a creation. To put it another way: the evidence that this hadith was created in response to the ʿĪsawiyyah—the correspondence between its matn and this movement—is strong, and cannot be overcome merely by positing that al-ʾAwzāʿī only created the hadith after ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s death and then speculating that al-ʾAwzāʿī would have viewed matters in a specific, contradiction-generating way.

In sum: (1) the link between al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith and the ʿĪsawiyyah is strong, such that the latter likely refers to the former; (2) the Levant contemporaneous to the rebellion of the ʿĪsawiyyah in the East fits comfortably as the context of origin for this hadith, given that the Levant must have been abuzz with news of the rebellion, and given also the plausibility of the spread of the ʿĪsawiyyah already at this early stage; (3) the Levant after ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s death also serves as a viable context of origin for this hadith, for the same reasons; (4) al-ʾAwzāʿī’s creating the hadith during the rebellion and his creating the hadith in the aftermath of the rebellion thus work equally well; and (5) it remains plausible that al-ʾAwzāʿī would have created the hadith even after ʾAbū ʿĪsá’s death.

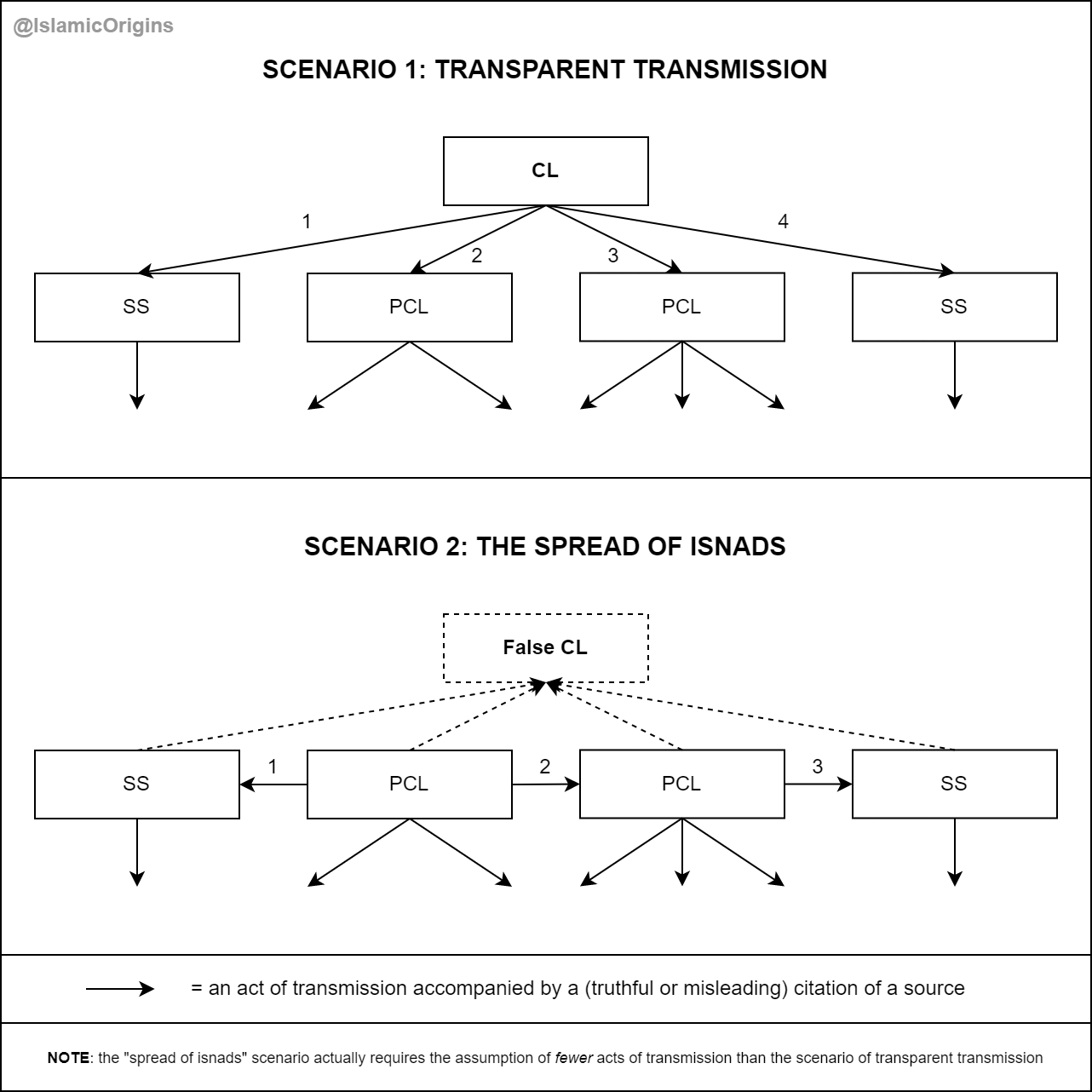

Part 2: False CLs and the Spread of Isnads

Let us now return to the other argument in favour of disassociating the relevant hadiths from the ʿĪsawiyyah: the appeal to a pre-ʿĪsawī CL. This argument assumes that, in establishing a hadith’s provenance, the existence of a putative CL in its isnads outweighs a close correlation between its matn and a specific historical event. Such an assumption is difficult to defend in light of the relevant scholarly dialectic—the last half-century of back-and-forth argumentation over the dating of hadiths according to CLs—summarised in chapter 1 of the unabridged version of my PhD dissertation. The problem here is straightforward: the genuineness of CLs is a heuristic or presumption, a general best explanation for the relevant isnad-matn correlations; the possibility of a false CL—the possibility that a putative CL emerged through a series of borrowings and reattributions—remains in any instance.[18] In other words, genuine CLs are not ironclad historical facts, but hypotheses or explanations for certain kinds of Hadith evidence, which can be overturned by stronger forms of counterevidence. To illustrate this point, consider the following hadith:

ʿUṯmān b. ʾabī Šaybah related to us: ‘Muʿāwiyah b. Hišām related to us: ‘ʿAlī b. Ṣāliḥ related to us, from Yazīd b. ʾabī Ziyād, from ʾIbrāhīm, from ʿAlqamah, from ʿAbd Allāh, who said: “When we were with the Messenger of God (ﷺ), some youngsters from the Banū Hāšim came by. When the Prophet (ﷺ) saw them, his eyes filled with tears and his colour changed. I said: ‘We still see in your face something that we dislike [seeing].’ Then he said: ‘Verily, we, the ʾAhl Bayt, [are those] for whom God has chosen the Hereafter over the mundane world. And verily, my ʾAhl Bayt will endure calamity, expulsion, and exile after me, until a people with black banners come from the East. Then they will ask for something good [i.e., the caliphate], but they will not be given it, so they will fight and attain victory. Then they will be given what they asked for [i.e., the caliphate], but they will not accept it [for themselves, instead] handing it over to a man from my ʾAhl Bayt. He will fill it [i.e., the caliphate] with justice, just as it was [previously] filled with injustice. Thus, whoever amongst you lives long enough to experience that, let him go to them [i.e., the Eastern forces], even if [it requires] crawling over snow!’”’”[19]

Most versions of this hadith converge in their isnads upon the key figure of Yazīd b. ʾabī Ziyād (Kufan; d. 137/754-755), citing ʾIbrāhīm al-Naḵaʿī (Kufan; d. 96/714), from ʿAlqamah b. Qays (Kufan; d. 62-65/681-685 or 72/691-692), from ʿAbd Allāh b. Masʿūd (Hijazo-Kufan; d. 32-33/652-654), from the Prophet.[20] Alongside this, two versions of the hadith converge in their isnads upon a common Eastern-Kufan strand back to al-Ḥakam b. ʿUtaybah (Kufan; d. 114-115/732-734), from ʾIbrāhīm, from ʿAlqamah or al-ʾAswad b. Yazīd (d. 75/694-695), from Ibn Masʿūd, from the Prophet;[21] and another version likewise reaches back, with a Kufan strand, to al-Ḥakam, from ʾIbrāhīm, from both ʿAlqamah and ʿAbīdah b. ʿAmr (Kufan; d. 72/691-692), from Ibn Masʿūd, from the Prophet.[22] In short, ʾIbrāhīm appears as the CL of this hadith, whilst Yazīd and al-Ḥakam appear as PCLs.

There can be little doubt that ʾIbrāhīm is a false CL here: the hadith in question describes how the suffering of the Banū Hāšim will be brought to an end by forces from the East bearing black banners, who will then hand over power to the Banū Hāšim—an obvious post-facto reference to the Umayyad suppression of the Banū Hāšim, the revolution of the black-clad Hāšimiyyah from Khurasan, and the establishment—or at least immanent victory—of the Abbasid Dynasty.[23] (One version seems to go even further, adding an element ostensibly referring to the post-Abbasid rebel and caliphal contender al-Nafs al-Zakiyyah.[24]) Given that this hadith likely postdates the start of the Abbasid Revolution (c. 129-132/747-750), and given also that both ʾIbrāhīm (d. 96/714) and al-Ḥakam (d. 114-115/732-734) died decades prior this event, it follows that ʾIbrāhīm is a false CL, and al-Ḥakam a false PCL, in this instance. Instead, we can reasonably posit that Yazīd b. ʾabī Ziyād—a Hashimid client who lived through the revolution—was the hadith’s true CL and creator;[25] that a tradent operating after al-Ḥakam borrowed Yazīd’s hadith and cited a false, parallel isnad back via al-Ḥakam to Yazīd’s alleged source ʾIbrāhīm; and that another tradent borrowed from this version in turn, redacted it to make it more specifically pro-ʿAlid, and bypassed his source with another false, parallel isnad back to al-Ḥakam.[26] This kind of borrowing and reattribution was an infamous and common practice in early Hadith culture, which the Hadith critics called tadlīs or sariqah (depending on the severity of the reattribution), and which modern scholars call “the spread of isnads” or “diving”.[27] Clearly, false CLs are a real problem, and the easiest way to expose them is precisely in pseudo-prophetical cases like this, when the hadith’s original historical context is clear.[28]

This brings us neatly back to the assumption that the appearance of a pre-ʿĪsawī CL for this hadith would demonstrate that the hadith cannot be a reference to the ʿĪsawiyyah, which we may now invert: the hadith likely refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah, so if the putative CL predates the ʿĪsawiyyah, that strongly indicates that the CL in this case is a product of false ascription. Thus, in the case under consideration, we could posit that one of the post-Yaḥyá PCLs (e.g., Šaybān b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān) is the hadith’s true creator, and that the remaining co-transmissions from Yaḥyá (e.g., those recorded by ʾAbān, Ibn Ḥanbal, Ibn ʿAsākir, and ʿAbd al-Razzāq) actually derived from him. Such a scenario would be quite easy in this instance, given that all of Yaḥyá’s relevant students were Basrans, which is to say: they overlapped in time and space.

In short, in any given case of a clear match between a hadith with a putative CL and a specific historical event (i.e., in any given case of a hadith with content that is blatantly anachronistic in respect to the Prophet or some other cited source), one of three scenarios will obtain. Firstly, the putative CL postdates the event in question: in this scenario, the CL could be the hadith’s creator, but could just as easily be a transmitter (i.e., from an earlier creator) as well. Indeed, if the hadith better matches the time and place of a source cited by the CL, this points strongly to the CL’s being a transmitter. Secondly, the putative CL, in contrast to their cited sources, coincides with the event in question: in this scenario, the CL is the prime candidate for being the hadith’s creator, although the possibility of its being an unacknowledged borrowing from an anonymous contemporary creator cannot be ruled out. Thirdly, the putative CL predates the event in question: this would be strong evidence that the putative CL is false (i.e., a product of successive borrowings and false ascriptions).

Part 3: Contamination and the Hadith of Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr

Of course, a false CL resulting from the spread of isnads is not the only option here: in such a situation, we might instead be dealing with a contaminated hadith network. This possibility was noted at the outset, but to explain more fully what such a scenario would involve, it is helpful to first summarise all of the versions or transmissions under consideration, and to consult a diagram thereof. To begin with, I was able to collate the following versions of Yaḥyá’s hadith:

ʾAbū Bakr b. ʾabī Šaybah (d. 235/849):

al-ʾAšyab—Šaybān—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed; Jews of Isfahan; Madinah; Lod; Jesus kills Antichrist; 40 years; justice.[29]

Ibn Ḥanbal (d. 241/855):

Sulaymān b. Dāwūd—Ḥarb b. Šaddād—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed; Jews of Isfahan; Madinah; Lod; Jesus kills Antichrist; 40 years; justice.[30]

ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾAḥmad (d. 290/903):

Hudbah—ʾAbān—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed.[31]

Ibn Ḥibbān (d. 354/965):

ʿImrān—ʿUṯmān b. ʾabī Šaybah—al-ʾAšyab—Šaybān—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed; Jews; Madinah; Lod; Jesus kills Antichrist; 40 years; justice.[32]

Ibn Mandah (d. 395/1005):

al-ʾAṣamm—al-Ṣāḡānī—Mūsá b. ʾIsmāʿīl—ʾAbān—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed.[33]

al-Bayhaqī (d. 458/1066):

ʿAlī b. ʾAḥmad—al-ʿAskarī—Jaʿfar—Ibn ʾabī ʾIyās—Šaybān—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed; Jews of Isfahan; Madinah; Lod; Jesus kills Antichrist; 40 years; justice.[34]

Ibn ʿAsākir (d. 519/1125):

al-Kirmānī—al-Ṭabasī—al-Ṣadafī—al-Ḥalīmī—ʾAbū al-Muwajjih—ʾAbān—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed; Jews of Isfahan; Madinah; town in Palestine; Jesus kills Antichrist; 40 years; justice.[35]

Ibn ʿAsākir (d. 519/1125):

Fāṭimah—Sibṭ Baḥruwayh—Ibn al-Muqriʾ—ʾAbū Yaʿlá—ʾAbū Ḵayṯamah—al-ʾAšyab—Šaybān—Yaḥyá—Ḥaḍramī—ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ—ʿĀʾišah:

Crying; Antichrist; protect; God is not one-eyed; Jews of Isfahan; Madinah; Lod; Jesus kills Antichrist; 40 years; justice.[36]

Alongside the foregoing, a short statement attributed to Yaḥyá relating to this topic is also recorded in two sources, both from ʿAbd al-Razzāq:

Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād (d. 228-229/842-844):

ʿAbd al-Razzāq—Maʿmar—Yaḥyá:

Majority of Jews of Isfahan follow Antichrist.[37]

al-Dabarī (d. 285-286/898-899):

ʿAbd al-Razzāq—Maʿmar—Yaḥyá:

Majority of Jews of Isfahan follow Antichrist.[38]

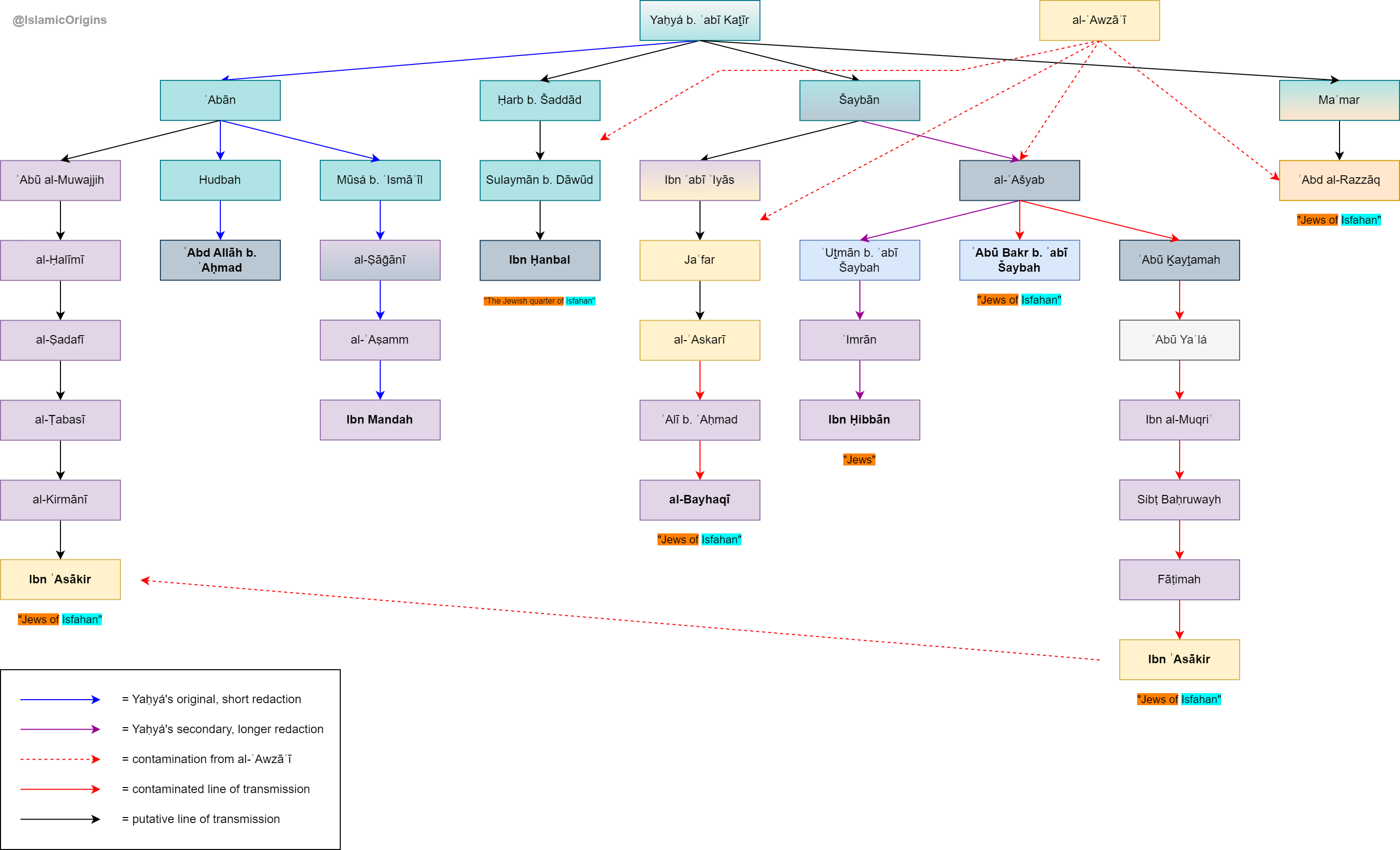

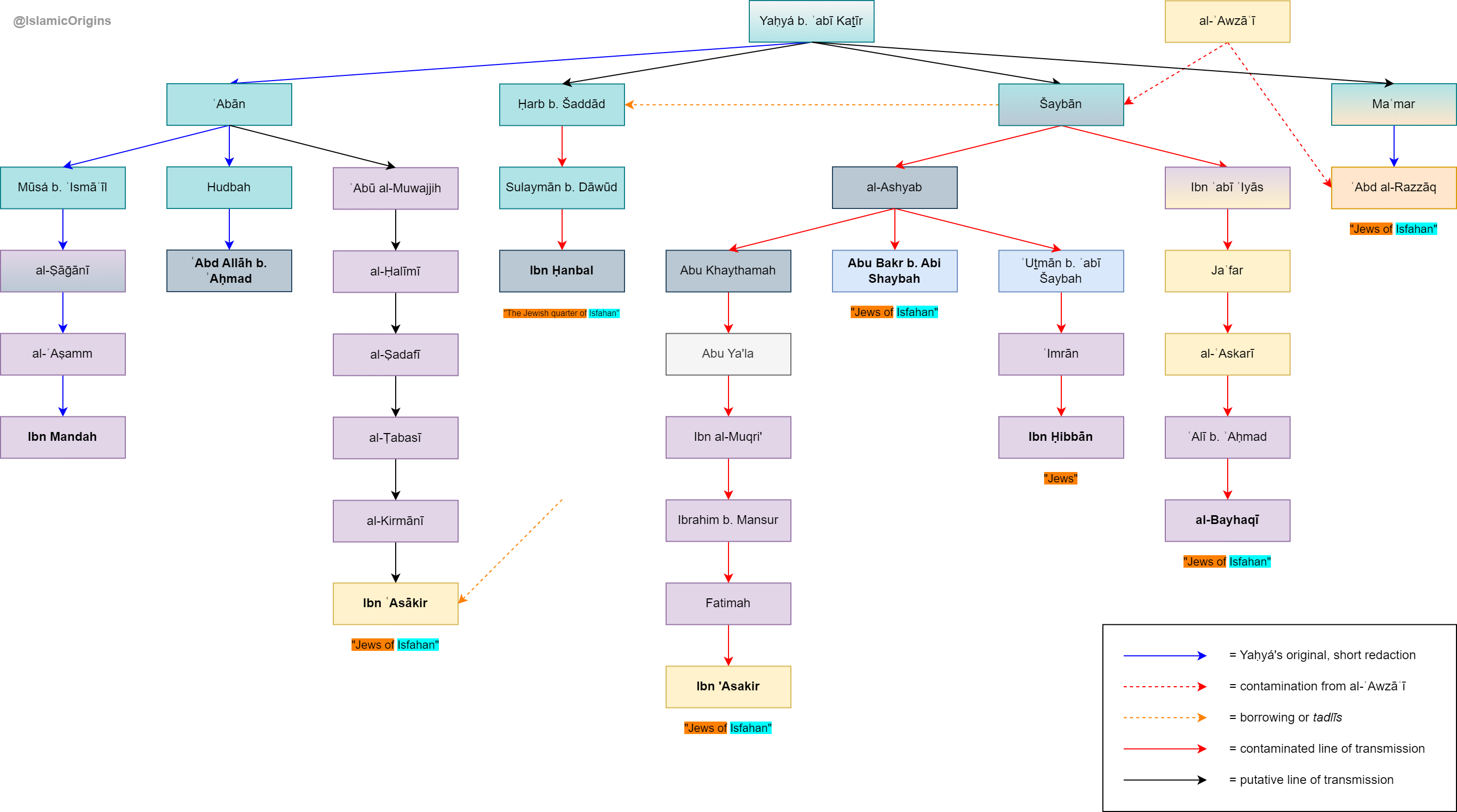

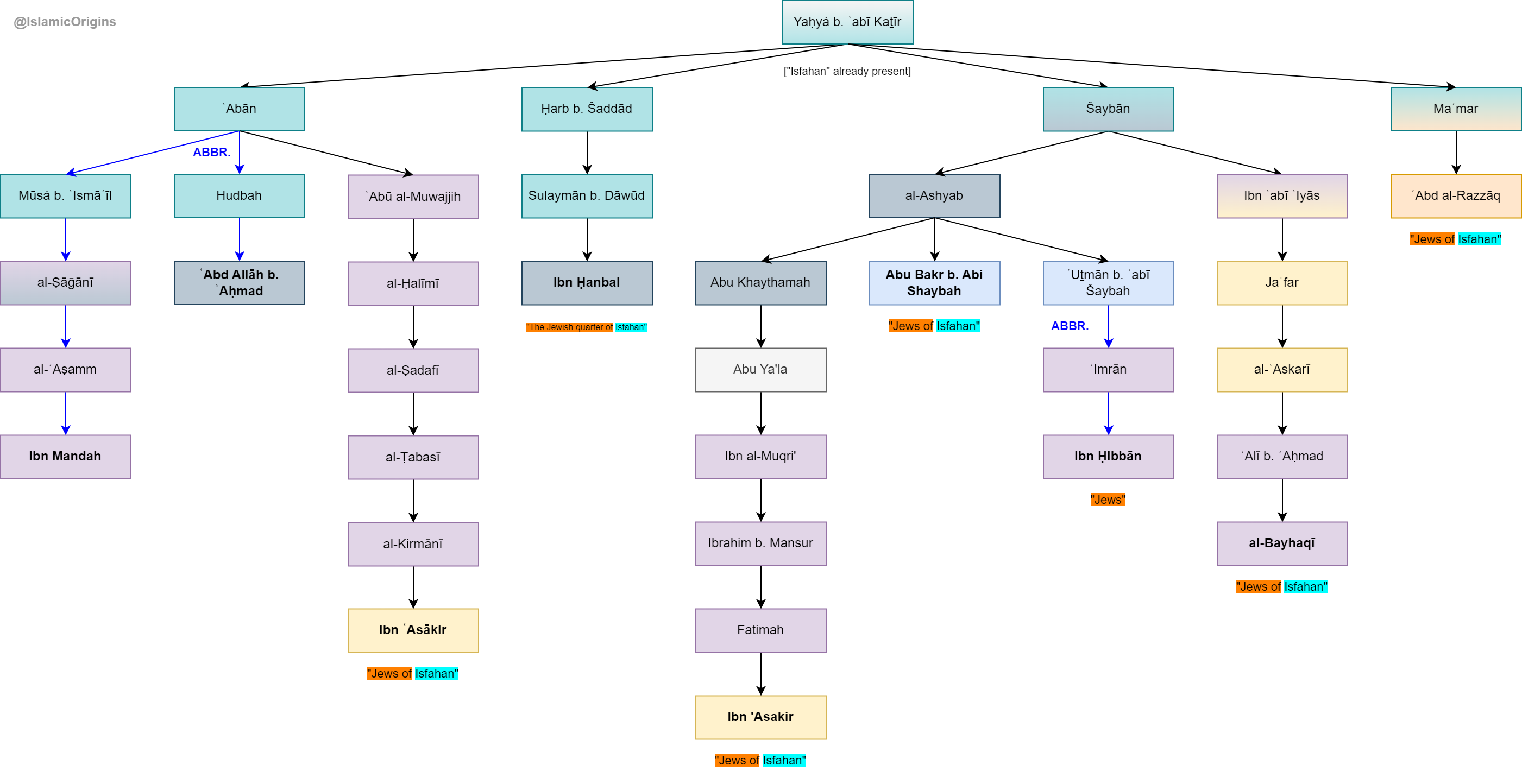

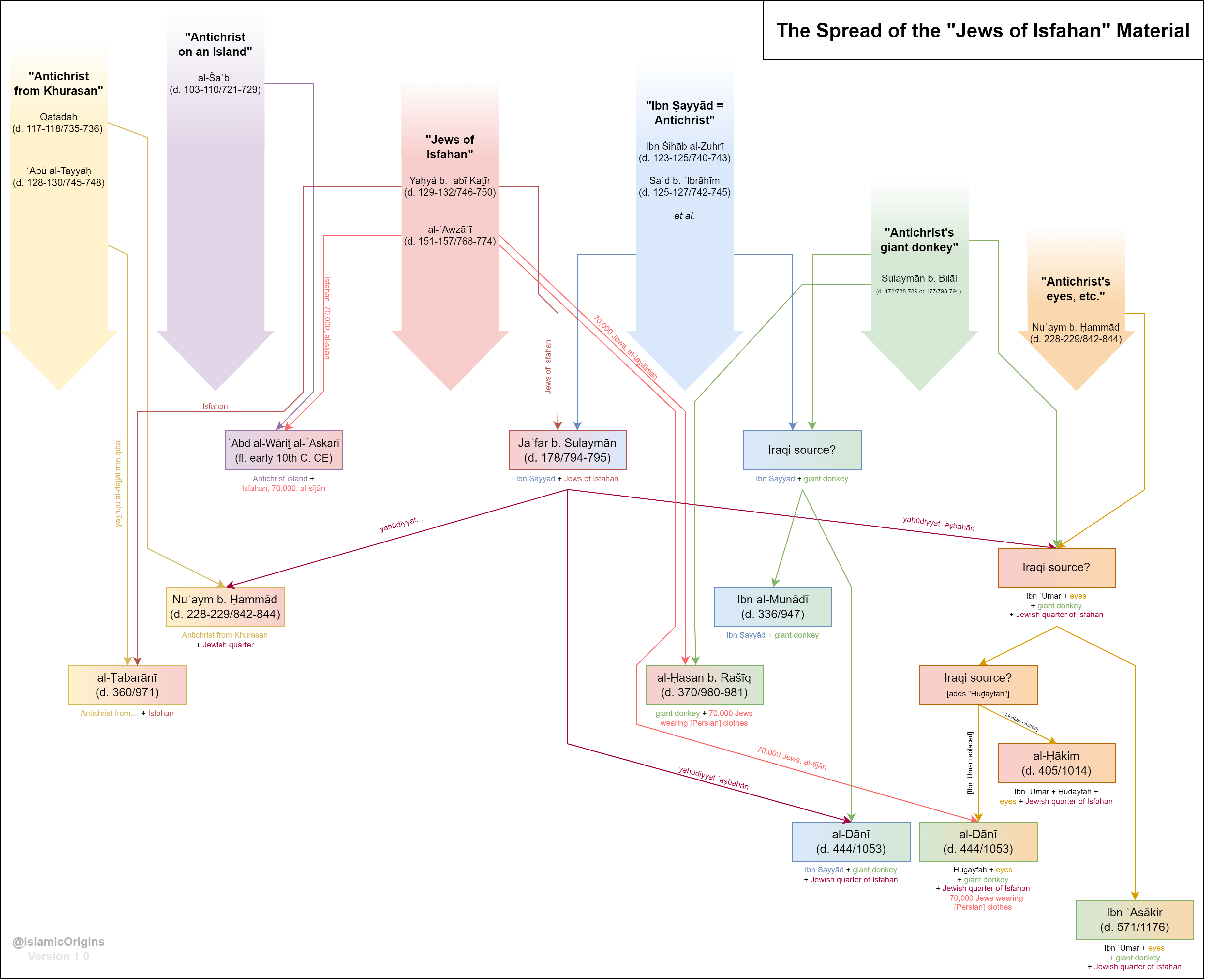

Taken altogether, these reports yield the following isnad-cum-matn diagram. To make the ensuing explanation easier, I have highlighted to “Jewish followers” element with the colour orange, and the “Isfahan” detail in particular with the colour aqua, whilst leaving all other elements and wordings in grey.

My original diagram

In my brief initial discussion of these hadiths on Twitter back in January of 2023, I pointed out that ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s report is not actually corroborated by the others, given that it is a different formulation, i.e., does not embody a distinctive redaction of the material in common with the others.[39] (Indeed, ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s simple formulation is closer to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s short hadith than the longer narrative otherwise attributed to Yaḥyá.) Thereafter, concerning the longer narrative, I argued that “most of the earliest recorded versions” (i.e., those recorded by ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾAḥmad, Ibn Ḥibbān, and Ibn Mandah) “don’t have ‘Isafahan’, which is mostly in later SSs [i.e., “single strand” isnads]. This is consistent with a general contamination from the more famous hadith, as we saw elsewhere.”[40] When my interlocutor at the time countered that the Isfahan detail is still present in two of the earliest sources (i.e., Ibn ʾabī Šaybah and Ibn Ḥanbal),[41] I responded: “Sure, but we also have early ones that lack it, and most corroboration for Isfahan is later SSs. We could easily be dealing with contamnination [sic] here. As I pointed out in my article, there are other instances of this in other Antichrist hadiths were such details bled over.”[42]

To elaborate all of this a bit more clearly, the idea here is that, as al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith spread and became famous, it influenced or contaminated different versions of Yaḥyá’s hadith as well, which variously thereby acquired the “Isfahan” detail, resulting in the illusion of this detail’s belong to Yaḥyá’s original formulation. The scenario here is similar to that proposed by Michael Cook, in his famous response to Josef van Ess:

But suppose we envisage instead the following transmission history. Aʿmash put into circulation a version without ‘acts’, and Shuʿba took this over. In the generation after Aʿmash a version with ‘acts’ appeared in Kūfa, and thanks to its greater polemical utility, swept the board there; some Baṣrans transmitting the tradition from Shuʿba were also influenced by it. This accounts for the fact that the Baṣran version with ‘acts’ is transmitted from Shuʿba from Aʿmash, without our having to assume the authenticity of the ascription of the feature in question to either. The process is simple and plausible; it can be described as ‘contamination’, or as a minor case of spread, here affecting not a whole tradition but merely a particular feature of it. We cannot show that this is how it happened; but it is at least as plausible a hypothesis as that put forward by van Ess.Van Ess is not unaware of the vulnerability of his argument to such a counter-hypothesis. But he prefers not to get involved with ‘imponderables’ and to keep clear of ‘speculation’. In the abstract, this is a splendid stance. But in the concrete, it is marred by an element of hypocrisy: why should the hypothesis, implicit in his method, that there was no such thing as contamination, be accounted any more ponderable or less speculative?[43]

This sort of thing is by no means mere speculation: for example, throughout ch. 2 of my study of the famous hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s marital age, I documented numerous likely instances of more famous and influential versions of the hadith contaminating or influencing more obscure or heterodox versions, not mention various instances of contamination or influencing from related hadiths. Likewise, as we shall see below, there are many likely instances of contamination that can be identified in other eschatological hadiths as well.

Thus, in this particular case, we could interpret: (1) the shorter version of the hadith, recorded by both ʿAbd Allāh and Ibn Mandah from the PCL ʾAbān, as Yaḥyá’s original formulation (i.e., from which the Antichrist’s travels, including the “Isfahan” detail, is absent); (2) Ibn ʿAsākir’s co-transmission from ʾAbān—which does not match ʿAbd Allāh and Ibn Mandah’s transmissions—as an error or dive deriving from a later version; (3) Ibn Ḥibbān’s version as embodying a secondary formulation by Yaḥyá, adding the Antichrist’s travels and even the element of his Jewish following, but not the “Isfahan” detail; and (4) the remaining versions, recorded Ibn Ḥanbal, Ibn ʾabī Šaybah, al-Bayhaqī, and Ibn ʿAsākir, as having been variously contaminated by the addition of the “Isfahan” detail—emanating from al-ʾAwzāʿī’s famous hadith—at some tertiary stage of development. Finally (5), ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s short ascription to Yaḥyá may also have been contaminated in this fashion (e.g., ʿAbd al-Razzāq himself may have inserted the “Isfahan” detail therein). In short, in this scenario, we have five separate instances of contamination to explain the presence of the “Jews of Isfahan” element across the different transmissions from Yaḥyá.

Alternatively, we might posit the foregoing scenario, but with the following alteration: rather than positing two separate instances of contamination in two lines of transmission emanating from the PCL al-ʾAšyab (respectively recorded by Ibn ʾabī Šaybah and Ibn ʿAsākir), we could instead posit that al-ʾAšyab himself was responsible for this addition. In other words, after transmitting a true version from Yaḥyá (containing only “the Jews”), al-ʾAšyab was influenced by al-ʾAwzāʿī’s spreading hadith and transmitted a second, contaminated version. In short, in this scenario, we have four separate instances of contamination to explain the presence of the “Jews of Isfahan” element across the different transmissions from Yaḥyá.

However, supposing that Ibn Ḥibbān’s “Jews” wording is actually just a slight abridgement—or generalisation—of a preceding “Jews of Isfahan” wording, we could instead posit the following scenario: (1) Yaḥyá only transmitted the short version of his hadith, which was preserved by the PCL ʾAbān, and thence by ʿAbd Allāh and Ibn Mandah; (2) Yaḥyá also transmitted this hadith to Šaybān, who was subsequently influenced by al-ʾAwzāʿī’s spreading hadith and added “the Jews of Isfahan” into a more elaborate version, which was thence inherited by Šaybān’s students; (3) thereafter, Yaḥyá’s student Ḥarb—or perhaps Ḥarb’s student al-Ṭayālisī—borrowed Šaybān’s contaminated hadith but suppressed Šaybān from the isnad; (4) meanwhile, Maʿmar or his student ʿAbd al-Razzāq was influenced by either al-ʾAwzāʿī’s spreading hadith or the contaminated version of Yaḥyá’s hadith and either created or updated an ascription to Yaḥyá; and (5) finally, someone between ʾAbān and Ibn ʿAsakār misattributed the contaminated version of Yaḥyá’s hadith via the former. (Of course, there are other variants of this hypothesis that could be formulated—for example, the roles of Šaybān and Ḥarb could be reversed, etc.) In short, in this scenario, we have two separate instances of contamination to explain the presence of the “Jews of Isfahan” element across the different transmissions from Yaḥyá, along with one instance of abridgement (to explain Ibn Ḥibbān’s version).

Of course, such explanations for the extant state of the hadith’s versions are ultimately less parsimonious than an explanation that accepts that the “Isfahan” detail belonged to the hadith’s original formulation (i.e., its urtext or ausgangstext), since this view would require only one instance of major abridgement (e.g., by the PCL ʾAbān, preserved by ʿAbd Allāh and Ibn Mandah) and one instance of minor abridgement (somewhere between the PCL al-ʾAšyab and Ibn Ḥibbān), rather than, for example, five instances of addition (as in the first scenario), or four instances of addition (as in the second scenario), or two instances of addition and a single instance of abridgement (as in the third scenario).

In this respect, the skepticism that has been expressed regarding my original suggestion that multiple versions of Yaḥyá’s hadith were contaminated is understandable, even if the skeptics in question do not explicitly appeal to parsimony, tending instead to merely list out the relevant data and assert contrary explanations therefor.[44] This by itself is obviously insufficient to overcome the alternative “contamination” explanation, which—as we have just seen—can explain the same data. What is lacking in the existing criticisms is argumentation, i.e., the reason why corroboration at multiple registers of transmission favours one view over the other, the reason why attestation by earlier source favours one view over the other, etc. Absent such argumentation, the existing criticisms simply assume the falsehood of the hypothesis that they are supposed to be refuting.

Moreover, even in light of parsimony, it cannot simply be assumed that the hadith in question actually originated with Yaḥyá. In other words, even if parsimony favours the assumption that the “Isfahan” detail was present in the original version of the hadith attributed to Yaḥyá, this has no bearing on Yaḥyá’s genuineness as a CL: the hypothetical ur-hadith in question could be something that was formulated and transmitted by Yaḥyá; or it could be something that was formulated and transmitted by one of his students, whence it spread to the others. Contrary to what is sometimes assumed,[45] the scenario of a false CL emerging through the spread of isnads is not more complicated than a scenario of genuine or transparent transmission. In both scenarios, in every instance of transmission, a tradent (e.g., Yaḥyá or one of his students) transmits to another tradent (e.g., another of Yaḥyá’s students), who in turn transmits to further tradents whilst citing a source (e.g., truthfully or misleadingly citing Yaḥyá).[46]

In short, even if we assume—in light of parsimony—that all extant versions of the hadith attributed to Yaḥyá ultimately derive from an ur-hadith that contained the “Isfahan” detail (and thus, that the detail’s absence from several versions is the product of abridgement or omission rather than addition), we are still left—at this point in the dialectic—without any good reason to accept that the ur-hadith in question it can be positively attributed to its putative source Yaḥyá.

This is not to say, however, that there is no reason to think that the hadith in question can be traced back to Yaḥyá. On the contrary, a proper ICMA can be mounted in favour of the hypothesis that (1) Yaḥyá actually disseminated this hadith and (2) included the “Jews of Isfahan” element therein. In what follows, I will render such an argument, before considering whether this really undermines my broader hypothesis that the relevant hadiths (both Yaḥyá’s and al-ʾAwzāʿī) postdate and refer to the ʿĪsawiyyah.

Part 4: An ICMA of the Hadith of Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr

The Antichrist hadith associated with the putative CL Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr (Basro-Yamāmī; d. 129-132/746-750) is variously recorded in: the Musnad of Ibn Ḥanbal, citing a Basran strand via Ḥarb b. Šaddād al-Yaškurī (Basran; d. 161/777-778) back to the putative CL Yaḥyá; the Muṣannaf of Ibn ʾabī Šaybah, the Ṣaḥīḥ of Ibn Ḥibbān, and the Taʾrīḵ Dimašq of Ibn ʿAsākir, all ultimately reaching back to the putative PCL al-Ḥasan b. Mūsá al-ʾAšyab (Baghdadi; d. 209/824), from the putative PCL Šaybān b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Naḥwī (Basro-Baghdadi; d. 164/780-781), from the putative CL Yaḥyá; the Baʿṯ of al-Bayhaqī, citing a parallel Levantine strand back to Šaybān; and the Sunnah of ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾAḥmad (twice), the ʾĪmān of Ibn Mandah, and (again) the Taʾrīḵ Dimašq of Ibn ʿAsākir, all ultimately reaching back to the putative PCL ʾAbān b. Yazīd al-ʿAṭṭār (Basran; fl. late 8th C. CE), from the putative CL Yaḥyá. In all of these transmissions, it is reported that the putative CL Yaḥyá cited Ḥaḍramī b. Lāḥiq al-Tamīmī al-ʾAʿraj (Yamāmī; d. early 8th C. CE), from ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ Ḏakwān al-Sammān (Madinan; d. 101/719-720), from ʿĀʾišah bt. ʾabī Bakr (Madinan; d. 57-58/677-678), the hadith’s putative source.

Alongside this hadith, there is also a short statement regarding the Antichrist recorded in the Fitan of Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād (twice) and ʾIsḥāq b. ʾIbrāhīm al-Dabarī’s recension of ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s recension of the Jāmiʿ of Maʿmar, both citing the putative CL ʿAbd al-Razzāq b. Hammām (Yemeni; d. 211/827), from Maʿmar b. Rāšid al-ʾAzdī (Basro-Yemeni; d. 152-154/769-771), from Yaḥyá, this time without citing any earlier sources.

To begin with, Ibn ʾabī Šaybah, Ibn Ḥibbān, and Ibn ʿAsākir’s transmissions from al-ʾAšyab, from Šaybān, along with al-Bayhaqī’s co-transmission from Šaybān, are more similar to each other than they are to all other versions of this hadith, or in other words: all of the transmissions from Šaybān constitute a distinctive sub-tradition within the overall tradition, sharing several rare and unique features.[47] Within this sub-tradition, the transmissions from al-ʾAšyab barely, but still noticeably, constitute a further sub-sub-tradition, sharing several additional features in common vis-à-vis al-Bayhaqī’s co-transmission from Šaybān.[48] All of this is consistent with both Šaybān and al-ʾAšyab’s being genuine PCLs, whose distinctive formulations or redactions of the hadith undergird (i.e., explain the rise of) the sub-tradition and sub-sub-tradition respectively associated with each.

Ibn Ḥibbān’s version has al-yahūd, in contrast to the yahūd ʾaṣbahān shared by Ibn ʾabī Šaybah and Ibn ʿAsākir’s co-transmissions from al-ʾAšyab, from Šaybān, and al-Bayhaqī’s co-transmission from Šaybān. The best explanation for this situation is that yahūd ʾaṣbahān was present in both Šaybān’s original redaction and al-ʾAšyab’s sub-redaction thereof, and that it was paraphrased or misremembered as al-yahūd at some point between al-ʾAšyab and Ibn Ḥibbān. It would be more complicated to inversely posit that al-yahūd was the original present in Šaybān and al-ʾAšyab’s redactions, since this would require two or more changes from al-yahūd to yahūd ʾaṣbahān—by Šaybān himself or a subsequent tradent, resulting in al-Bayhaqī’s version; and by al-ʾAšyab himself or two subsequent tradents, resulting in Ibn ʾabī Šaybah and Ibn ʿAsākir’s versions. In other words, parsimony favours the hypothesis that al-yahūd in Ibn Ḥibbān’s version represents a secondary distortion of the original yahūd ʾaṣbahān in al-ʾAšyab’s redaction. This is strengthened by the fact that yahūd ʾaṣbahān is present in the earliest source attesting al-ʾAšyab’s redaction (i.e., the Muṣannaf of Ibn ʾabī Šaybah), whereas al-yahūd is present in a later source (i.e., the Ṣaḥīḥ of Ibn Ḥibbān): all else being equal, the earlier attested version is to be preferred in the reconstruction of an urtext, since there was less time for material to be distorted in the course of the oral transmission leading up to the earlier source, in comparison to the later source. Or, to put it another way: the later the source, the more likely it is to be distorted, all else being equal.[49]

ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾAḥmad and Ibn Mandah’s transmissions from ʾAbān are also far more similar to each other than they are to all other versions, sharing a number of unique features in common vis-à-vis all other versions.[50] Once again, a distinctive sub-tradition correlates with a PCL, which is consistent with ʾAbān’s being a genuine common source, whose particular redaction undergirds the sub-tradition in question. By contrast, Ibn ʿAsākir’s co-transmission from ʾAbān does not embody this distinctive sub-tradition, being instead markedly more similar to al-ʾAšyab’s distinctive sub-tradition.[51] This could be explained by positing that ʾAbān transmitted two different versions of the hadith: an earlier, unabridged version (preserved by Ibn ʿAsākir) that inherited the same features as al-ʾAšyab’s version; and a subsequent, abridged version (preserved by ʿAbd Allāh and Ibn Mandah) that deviated therefrom. However, it could equally be explained by positing that Ibn ʿAsākir’s co-transmission from ʾAbān was contaminated by or otherwise derived from al-ʾAšyab’s sub-tradition. Doubt thus surrounds Ibn ʿAsākir’s co-transmission from ʾAbān, which cannot be affirmed as actually deriving from him, in contrast to ʿAbd Allāh and Ibn Mandah’s versions.

All of this leaves us with the following: (1) Šaybān, a reconstructed PCL who directly cites Yaḥyá; (2) ʾAbān, another reconstructed PCL who also directly cites Yaḥyá; (3) Ibn Ḥanbal, citing a strand back to Yaḥyá; and (4) Ibn ʿAsākir, citing a strand via ʾAbān to Yaḥyá, which is suspect, but which may still preserve useful data. All of these reports are far more similar to each other than they are to all other related material (e.g., al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith) and thus constitute a distinctive overall tradition, which matches their citation of a common source. This is consistent with Yaḥyá’s being a genuine CL, whose particular formulation undergirds this tradition. There are of course various differences between these different versions, but by applying the same principles outlined above, the following urtext can reconstructed and reasonably attributed to Yaḥyá:

Al-Ḥaḍramī b. Lāḥiq {related to me}[52] that ʾAbū Ṣāliḥ related to him from ʿĀʾišah, who said: “The Messenger of God entered upon me whilst I was crying, then he said:[53] ‘Why are you crying?’ I said: ‘O Messenger of God,[54] you mentioned the Antichrist, so I cried.’[55] Then he[56] said: ‘Do not cry,[57] for if[58] he[59] emerges whilst I am still alive, I will protect all of you from him; and if I have died [by that point],[60] then verily, your Lord[61] is not one-eyed! And verily the Jews of Isfahan will go out with him,[62] and he will travel[63] until he alights in the vicinity of Madinah,[64] which will have seven gates at that time—and upon each gate[65] there will be two angels. Then the evil ones amongst its people[66] will go out to [join] him, {then he will depart}[67] {and travel}[68] until he comes to {a city in Palestine, to the Gate of} Lod.[69] Then Jesus,[70] will descend and slay him. Thereafter, Jesus will remain[71] on Earth for forty years, or close to forty years,[72] as a just ruler and a fair judge.’”

That the final elements—concerning the Antichrist’s travels, from Isfahan to Lod—can be traced back to Yaḥyá, despite their absence from the redaction attributable to the PCL ʾAbān, seems probable: they are part of the distinctive material that is associated with (i.e., co-attested from) Yaḥyá.

This in turn creates several possible explanations for ʾAbān’s version: (1) it was abridged by ʾAbān himself, who originally received a longer version, which does not otherwise survive via him; (2) it was abridged by ʾAbān himself, who originally received a longer version, which he also transmitted, and which survives via Ibn ʿAsākir (although cf. the oddity of the dissimilarity thereof to the other transmissions from ʾAbān, even in those places where the same elements are present); (3) it was abridged by Yaḥyá and thence preserved by ʾAbān, whilst Šaybān and Ibn Ḥanbal preserved the earlier, original, longer version from Yaḥyá; or (4) it was the original version articulated by Yaḥyá (thence preserved by ʾAbān), which Yaḥyá subsequently expanded into a longer version (thence preserved by Šaybān and Ibn Ḥanbal).

Finally, the reports recorded by Nuʿaym (twice) and al-Dabarī are far more similar to each other than they are to all related material (e.g., al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith and Yaḥyá’s hadith) and certainly constitute a distinctive tradition, which is consistent with their deriving from the underlying formulation of their commonly cited source, ʿAbd al-Razzāq, to whom the following urtext can be attributed:

Maʿmar {said}:[73] ‘Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr {reported to me},[74] relating something thereon (yarwī-hi)—he said: “The majority of those who follow the Antichrist will be the Jews of Isfahan.”’[75]

Some uncertainty surrounds ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s ascription, which does not directly corroborate, and is not directly corroborated by, the preceding hadith from Yaḥyá: although the content of the former overlaps with an element in the latter, they are different formulations, i.e., they do not embody a distinctive tradition attributable to a common source. On the contrary, ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s ascription is actually more similar to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s shorter hadith on this subject, although it differs in some respects therefrom as well. Thus, on purely ICMA grounds, ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s report cannot be identified as a genuine co-transmission from Yaḥyá with any degree of confidence.

For all that, it seems hard to imagine that ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s ascription to Yaḥyá of a statement predicting that the Jews of Isfahan will follow the Antichrist is merely coincidental with the fact that Yaḥyá disseminated a hadith predicting that the Jews of Isfahan will follow the Antichrist: either Yaḥyá spoke about the same subject in different ways (i.e., in both a statement and a hadith); the statement attributed to Yaḥyá was been contaminated by his hadith (e.g., to include the “Isfahan” detail), given their similar topics; or else Yaḥyá’s statement was somehow falsely created and attributed to him at some secondary stage (e.g., by Maʿmar or ʿAbd al-Razzāq) on the basis of his hadith.

The Criterion of Dissimilarity, in conjunction with our established background knowledge on ascriptional tendencies and authority preferences in Hadith in the late 8th and early 9th Centuries CE,[76] militates against the last of these possibilities: if indeed Maʿmar or ʿAbd al-Razzāq had fabricated a statement and attributed it to Yaḥyá, inspired by and building upon Yaḥyá’s hadith, then it is odd that they did not provide this fabrication with an isnad reaching all the way back to the Prophet. This suggests that the statement from Yaḥyá was not fabricated, although it does not rule out possibility of contamination (e.g., the secondary insertion of the “Isfahan” element from Yaḥyá’s related hadith, or even al-ʾAwzāʿī’s related hadith): absent co-transmissions of this particular formulation from Yaḥyá, its original form remains uncertain.[77]

Of course, none of the foregoing precludes a false CL scenario: as I noted in my PhD dissertation, the spread of isnads can in fact account for the same data as the ICMA (i.e., isnad-matn correlations, which the ICMA seeks to explain in terms of genuine and transparent transmission from a CL).[78] However, as I also noted in my dissertation, a genuine CL scenario generally seems preferable as an explanation for such data, given that it usually generates a general model of declining variation in transmission (from the CL, to the PCLs, to the extant sources) that broadly matches our established background knowledge regarding the inverse and proportional rise of systematic transmission, written transmission, and Hadith criticism.[79] Thus, all else being equal, I would conclude that Yaḥyá is a genuine CL in this instance.

In sum, a standard ICMA of the hadith attributed to Yaḥyá provides a pro-tanto justification not just for the general conclusion that the hadith originated with him, but also for the specific conclusion that the “Isfahan” element was present already in his original articulation thereof. More uncertainty surrounds ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s ascription via Maʿmar to Yaḥyá, which is uncorroborated; but if indeed Yaḥyá disseminated a hadith about the Jews of Isfahan, it is reasonable to suppose that the statement about the Jews of Isfahan recorded by ʿAbd al-Razzāq also originated with him. In other words, as long as all else remains equal, all of these conclusions are reasonable.

Part 5: The Year of Yaḥyá’s Death

Of course, as was again already intimated, all else may not be equal in this case: if indeed Yaḥyá died before the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah, this would be strong grounds for preferring a more skeptical explanation for the relevant hadith data: either different lines of transmission emanating from Yaḥyá were contaminated at a secondary stage by the “Isfahan” detail, or else Yaḥyá is a false CL whose putative hadith actually originated with one of his ʿĪsawiyyah-contemporaneous students and thence spread to the latter’s contemporaries, who bypassed the true source in favour of citing Yaḥyá directly. In short, if indeed it were the case that Yaḥyá predated the ʿĪsawiyyah, we would be justified in treating him like ʾIbrāhīm al-Naḵaʿī in the abovementioned case: whilst a straightforward ICMA explanation for the textual data would be that the putative CL is genuine, such an analysis (i.e., the general considerations of the ICMA) are overruled by a broader historical-critical analysis of the hadith’s flagrantly anachronistic content. As with ʾIbrāhīm, so too with Yaḥyá.

However, such an argument may be unnecessary in this case, for it turns out that Yaḥyá did not necessarily predate the ʿĪsawiyyah. As noted in my previous blog article, Sean Anthony has argued that the ʿĪsawiyyah arose during the reign of Marwān b. Muḥammad (c. 127-132/744-750)—when ʾAbū ʿĪsá started preaching and attracting followers—and rebelled during the reign of al-Manṣūr (c. 136-158/754-775).[80] As it happens, the era of the initial rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah—the reign of Marwān—overlaps with the end of Yaḥyá’s life, whose date of death is variously reported as 129/746-747, or 130ish/747-748ish, or 132/749-750.

The biographical authority Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (Syrian; d. 748/1348) recorded the first and last of these years of death and stated, “the first is sounder”,[81] but failed to provide a reason for this opinion. Perhaps he held it due to his perception that the former was related by a mass of authorities,[82] but in actual fact, all of the reports on Yaḥyá’s year of death recorded across the biographical literature appear to boil down to the conflicting statements of only a few early authorities:

ʾAbū Nuʿaym al-Faḍl b. Dukayn (Kufan; d. 218-219/833-834):

“{Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr} died in the year 129.”[83]

ʿAlī b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Madīnī (Basran; d. 234/849):

“Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr; his teknonym was ʾAbū Naṣr; he died in the year 132, in al-Yamāmah.”[84]

Muḥammad b. ʾIsmāʿīl al-Buḵārī (Transoxanian; d. 256/870):

“ʿAlī [b. al-Madīnī] said: ‘He died a year after ʾAyyūb [al-Saḵtiyānī], in the year 132.’ And ʾAbū Nuʿaym said: ‘He died in the year 129.’”[85]

Muḥammad b. ʿĪsá al-Tirmiḏī (Transoxanian; d. 279/892):

“Muḥammad [al-Buḵārī] said: ‘Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr; his teknonym was ʾAbū Naṣr; and he died in the year 132.’”[86]

ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾAḥmad (d. 290/903):

“I found [the following] in a book of my father’s, in his handwriting: ‘I reported from ʿAbd Allāh b. Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr [Yamāmī; fl. turn of 8th C. CE?] that his father died in the year 129.’”[87]

ʾAbū al-Maymūn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Bajalī (Damascene; d. 347/958-959):

“ʾAbū Zurʿah [Damascene; d. 280-281/893-895] said: ‘And Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr died in the year 129.’ ʾAbū Zurʿah [also] related to us—he said: ‘I said to [Duḥaym] ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾIbrāhīm [Damascene; d. 245/859]: “When did Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr die?” He said: “In the year 130, or close thereto.”’”[88]

ʾAḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Kalābāḏī (Transoxanian; d. 398/1008):

“Al-Buḵārī said: ‘ʾAbū Nuʿaym said: “He died in the year 129.”’ And ʿAmr b. ʿAlī [al-Fallās; Basran; d. 249/863-864] said the same thing. And ʿAlī b. al-Madīnī said: ‘He died in the year 132.’ And ʾAbū ʿĪsá [al-Tirmiḏī] said the same thing as ʿAlī.”[89]

Even some of these sources—for example, al-Fallās and al-Buḵārī—were presumably just repeating information from the earlier sources. In other words, al-Ḏahabī here may have been misled by a phantom consensus in the biographical literature—a common pitfall for scholars who rely upon the Islamic historical corpus, as Lawrence Conrad has noted:

There are also times when it seems that the rules of evidence that prevail everywhere else in historical studies are simply waived off when it comes to the study of early Islam. A report generated in a particular time and place, and then cited 30 times subsequently in other later texts, will be cited for all 30 attestations as if these are independent witnesses.[90]

Setting aside such appeals to the majority, then, is there any reason to prefer one report over the other? On the one hand, ʾAbū Nuʿaym is the earliest of those who recorded Yaḥyá’s year of death, which might give a slight edge to his report; but Ibn al-Madīnī and Duḥaym were not much later than he, so “earliness” does not mean much in this case. However, if ʿAbd Allāh’s report of his discovery of a note left by his father mentioning a transmission from Yaḥyá’s son ʿAbd Allāh is to be trusted, then the year 129 AH probably has the edge here: all else being equal, it seems reasonable to prioritise the statement of a family member on such an issue.

There is also a report cited by al-Ḏahabī[91] that conceivably militates against 132 AH in particular as Yaḥyá’s year of death, which may be another reason why al-Ḏahabī preferred 129 AH instead: according to Mūsá b. ʾIsmāʿīl (Basran; d. 223/838), “I heard Wuhayb {b. Ḵālid say}: ‘I heard ʾAyyūb {al-Saḵtiyānī} say: “There is no one like Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr who remains on {the face of} the Earth.”’”[92] This could be a reflection on Yaḥyá’s recent death by ʾAyyūb, who himself died in 131/749 or 132/750.[93] This would seem to contradict al-Buḵārī’s report from Ibn al-Madīnī that Yaḥyá “died a year after ʾAyyūb, in the year 132,”[94] and it would also seem to imply that Yaḥyá died prior to 131 or 132 AH. Of course, Mūsá’s hyperbolic ascription to ʾAyyūb could easily be a later fabrication designed to praise Yaḥyá or defend his somewhat questionable reputation[95] and thus counts for little;[96] and it could also be a statement about a living contemporary in any case, since it does not explicitly mention Yaḥyá’s death. By contrast, the following report—recorded by ʾAḥmad b. Muḥriz (Baghdadi; fl. mid-to-late 8th C. CE)—is far less suspect:

I heard Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn say: “Ibn ʿUlayyah said: ‘[News of] the death of Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr came to us when we were with ʾAyyūb.’”He said: “And ʾIsmāʿīl [b. ʿUlayyah] came to sit [and study] with ʾAyyūb two years before his death.”

I heard Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn say: “Ibn ʿUlayyah said: ‘ʾAyyūb died in the year 132. We set with him two years before his death. Ibn ʿAwn was two years older than ʾAyyūb, but Ibn ʿAwn died ten years after ʾAyyūb.’”[97]

Even this report does not actually contradict the report that Yaḥyá died in 132 AH, however. Rather, it only contradicts the report that Yaḥyá died after ʾAyyūb, which presumably incorporates the alternative death-date of 131 AH elsewhere reported for ʾAyyūb. In other words, it is entirely possible that Yaḥyá died in 132 AH (per Ibn al-Madīnī); that Yaḥyá died before ʾAyyūb (per Ibn ʿUlayyah); and that ʾAyyūb also died, at a later date, in 132 AH (per Ibn ʿUlayyah); all of these propositions are compatible. We are thus left without any strong evidence pointing in any particular direction, other than ʿAbd Allāh’s report.

This is a familiar situation with early Muslim authorities and tradents, whose biographical information (e.g., names, nicknames, affiliations, locations, dates of birth, dates of death, and reliability) often seem to have been derived not from independent memories of their lives and circumstances, but from the hadiths that they transmitted, or the isnads in which they are cited (e.g., how they are referred to therein; to whom they transmitted; from whom they transmitted; etc.).[98] Such biographical data should thus be taken with a grain of salt, or in this particular case: whilst it seems likely that Yaḥyá died at some point during the middle or end of the reign of Marwān, the exact year of his death remains uncertain, even if 129 AH probably has the edge here.

In sum: (1) Yaḥyá reportedly died in either 129, 130ish, or 132 AH; (2) al-Ḏahabī preferred 129 AH, but gave no argument to this effect, and plausibly held this view on the basis of dubious and equivocal evidence; (2) Mūsá b. ʾIsmāʿīl’s ascription to ʾAyyūb (that Yaḥyá was now unmatched on Earth) could imply that Yaḥyá died before ʾAyyūb (i.e., before 131 or 132 AH), but the scenario could also be set during Yaḥyá’s lifetime and is highly suspect in any case; and (4) Ibn Maʿīn’s report from Ibn ʿUlayyah, to the effect that Yaḥyá died before ʾAyyūb, is equivocal. In short, whilst all of the relevant sources agree that Yaḥyá died at some point during the middle or end of the reign of Marwān, the exact year of his death remains uncertain, though 129 AH seems more probable.

Part 6: The Implications of Yaḥyá as a Genuine CL

In light of the preceding, we can now return to the chronological question of whether Yaḥyá could have created this hadith in response to the ʿĪsawiyyah. In this regard, a statement from my original blog article remains relevant:

…the ʿĪsāwiyyah probably arose after 744 CE and rebelled after 754 CE. This creates a much later terminus a quo for our hadith—more likely 754 ff. CE than 744 ff. CE, since the rebellion of this messianic sect in Isfahan seems more likely to have attracted the polemical attention of Muslims in other regions than their mere appearance (i.e., alongside any other number of small religious movements and sects under the caliphate).

This remains true: the creation of a text hostile to ʿĪsawiyyah would be more expected from 754 ff. CE, the time of their greater notoriety (i.e., when they rebelled) onwards; as opposed to 744 ff. CE, when they were presumably lesser known (i.e., when they merely arose). However, this does not preclude the possibility of an earlier creation—on the contrary, 744 ff. CE, when the ʿĪsawiyyah appeared, is the earliest possible date for the creation of a reference thereto, whilst 754 ff. CE, when the ʿĪsawiyyah rebelled, is the more expected date for the creation of a reference thereto. In other words, strictly speaking, 744 ff. CEis the terminus a quo for the hadiths under consideration.

Thus, even if we accept—following the preceding ICMA—that Yaḥyá was a genuine CL, and thus the source, of a hadith describing how the Jews of Isfahan will follow the Antichrist, this does not necessarily contradict the hypothesis that this hadith refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah (i.e., along the lines that Yaḥyá died prior to the earliest possible point at which a hadith could be created about the ʿĪsawiyyah). On the contrary, the last few years of Yaḥyá’s life (127-129/744-746 at least, and 127-132/744-750 at most) overlapped with the era of the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah (c. 127-132/744-750), which means that it is possible that Yaḥyá lived to see the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah, which in turn means that it is possible that Yaḥyá still created his hadith in reaction to the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah. Thus, if indeed Yaḥyá was a genuine CL, this is still compatible with the hypothesis that his hadith—not to mention al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith—was created in response to the ʿĪsawiyyah.

Of course, there is uncertainty here: we do not know for sure the exact year in which Yaḥyá died, and we also do not know the exact year in which the ʿĪsawiyyah sprang up, which means that the possibility remains that the former occurred prior to the latter. However, the possibility that the latter occurred prior to the former also remains, which means that Yaḥyá’s being a genuine CL cannot be used to refute the hypothesis that the “Jews of Isfahan” hadiths were post-facto creations referring to the ʿĪsawiyyah. In other words, Yaḥyá’s being a genuine CL is still consistent with a post-facto creation hypothesis.

Thus, even if we assume, for the sake of argument, that an ICMA-consistent CL is an ironclad historical fact, the link between the hadith’s content and the ʿĪsawiyyah also remains highly likely. In light of this, the most likely explanation for the relevant data would not be that the hadith does not refer to the ʿĪsawiyyah, but rather, that the CL Yaḥyá created the hadith at the very end of his life (i.e., in the final 2-5 years of his life), in response to the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah at that time. In other words, the hadith’s being a creation in reaction to the later rebellion of the ʿĪsawiyyah is certainly more expected than its being a creation in reaction merely to their earlier rise; but the latter in turn is more expected than the complete coincidence that a hadith would just so happen to correspond to the ʿĪsawiyyah, not to mention a hadith that is associated with a CL who just so happens to have lived unto the era of the ʿĪsawiyyah.

Yaḥyá’s candidacy as the creator of this hadith is only strengthened by his Basran provenance—for, as it happens, the city of Basrah in Iraq was closely linked to Isfahan, in several ways: Basrah was located in the neighbouring region to Isfahan; Isfahan was conquered in the first place by a Basran army, at least according to some reports; and, from the time of Isfahan’s conquest unto the Umayyad period (i.e., unto Yaḥyá’s lifetime), the city “came under the jurisdiction of the governors of Baṣra and ʿIrāḳ, who usually appointed the governors of Iṣfahān.”[99] Likewise, Basran scholars seem to predominate in the transmission of Hadith to Isfahan throughout the city’s history, which reinforces the close ties between Basrah and Isfahan in particular.[100] It is thus completely plausible that word of the rise of a Jewish messianic movement in Isfahan reached the Basrans in general and the elderly Yaḥyá in particular, who was thereby inspired—amidst the apocalyptic fervour of the final years of the Umayyad Dynasty—to incorporate something about this into a hadith about the Antichrist.

There is only one problem with all of this: it is widely reported in the biographical literature that Yaḥyá moved from Basrah to the central Arabian region of al-Yamāmah, where he spent the later part of his life. Thus, it is variously reported of Yaḥyá: that “he was from amongst the People of Basrah, then he moved (taḥawwala) to al-Yamāmah”;[101] that “he was a perfume-seller (ʿaṭṭār) in al-Yamāmah”;[102] that “he died in the year 132, in al-Yamāmah”;[103] that “al-ʾAwzāʿī heard from Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr in al-Yamāmah”;[104] that he was “the one who used to live (yaskunu) in al-Yamāmah”;[105] that “he used to live (kāna yaskunu) in al-Yamāmah, and he was Basran in origin”;[106] that he was “a Basran [who] departed (ḵaraja) to al-Yamāmah, after which he continued to transmit Hadith; al-ʾAwzāʿī heard from him in Basrah and in al-Yamāmah”;[107] that he was “the jurist of the People of al-Yamāmah”;[108] that “he was Basran, then he moved (taḥawwala) to al-Yamāmah”;[109] that he was “a Basran [who] relocated (intaqala) to al-Yamāmah”;[110] that “he was Basran, then he relocated (intaqala) to al-Yamāmah”;[111] that he was “from the People of Basrah; he settled (sakana) in al-Yamāmah… and he died in the year 129 in al-Yamāmah”;[112] and so on, so forth. There is even a report in which Yaḥyá himself identifies as Yamāmī during a visit to Makkah, recorded by Ḍamrah b. Rabīʿah (Levantine; d. 202/818):

Bašīr b. Ṣāliḥ said: “Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr asked ʿAṭāʾ [b. ʾabī Rabāḥ] a question, then he [i.e., ʿAṭāʾ] said: ‘Where do you live?’ He said: ‘Al-Yamāmah.’ He said: ‘What is your [opinion] about Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr?’ Yaḥyá said: ‘Thereafter, I did move myself for some time [i.e., due to shock]!’”[113]

In short, it seems certain that, whilst Yaḥyá originated in Basrah, he spent the end of his life in al-Yamāmah. Given that Yaḥyá only transmitted his Antichrist hadith to his Basran students, this might be taken to suggest that Yaḥyá transmitted this hadith prior to his migration from Basrah to al-Yamāmah, which presumably occurred prior to the reign of Marwān and the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah.[114]

This problem is easily solved by an internal feature of the hadith itself, however: whilst it is true that Yaḥyá only appears to have transmitted his hadith to Basrans, he cited a Yamāmī source—Ḥaḍramī b. Lāḥiq—therefor.[115] This is by no means an isolated case: for example, Maʿmar, another of Yaḥyá’s Basran students,[116] also seems to have transmitted a hadith from Yaḥyá that the latter sourced from his Yamāmī predecessor Ḍamḍam b. Jaws al-Hiffānī;[117] and Šaybān, yet another of Yaḥyá’s Basran students, likewise seems to have transmitted a hadith from Yaḥyá, from Ḍamḍam.[118] Given that Yaḥyá presumably began to cite Yamāmī sources after he moved to al-Yamāmah,[119] all of this strongly suggests either that Yaḥyá would return to his native Basrah at times (where he would cite Yamāmī sources), and/or that his Basran students—including the famously itinerant Maʿmar—would make the trek down to al-Yamāmah to visit him (where he would cite local sources to them).[120] Additionally, some Basrans may have corresponded with their famous expatriate in al-Yamāmah by means of letters, as indeed seems to be attested in one case.[121] Either way, Yaḥyá likely retained close links with Basrah and his Basran students, which not only helps to explain how he was able to transmit the Antichrist hadith to some of his Basran students after he had moved to al-Yamāmah, but also provides a plausible means by which news of the ʿĪsawiyyah could have reached Yaḥyá in the first place. It is quite easy to imagine Yaḥyá hearing the news of a Jewish messianic movement arising in Isfahan from some Basran students and then informing these students of something he heard from a Yamāmī source relating thereto, which is to say: the creation of this hadith by Yaḥyá in these circumstances remains plausible.

We are thus left with the following set of facts: the hadith associated with the CL Yaḥyá likely refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah; the CL Yaḥyá lived unto the era—the reign of Marwān—in which the ʿĪsawiyyah arose; and the CL Yaḥyá also hailed from a city with close links to the city in which the ʿĪsawiyyah arose. It is difficult to imagine that all of this is a coincidence, so how is it to be explained? If indeed Yaḥyá was a genuine CL, the most likely explanation would be that Yaḥyá heard of the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah and created the hadith—whether ex-nihilo or ex-materia—in reference to their movement. Needless to say, Yaḥyá’s ascription of this hadith to a pre-ʿĪsawī source is almost certainly false: in its extant form at least, the hadith is very unlikely to predate the reign of Marwān, if Anthony’s chronology of the ʿĪsawiyyah is to be trusted.

In sum: (1) Yaḥyá’s hadith likely refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah; (2) the end of Yaḥyá’s life (i.e., somewhere between the middle and end of Marwān’s reign) coincides with the time-period in which the ʿĪsawiyyah arose (i.e., during the reign of Marwān); (3) Yaḥyá hailed from Basrah, a city with close links to Isfahan (i.e., the base of the ʿĪsawiyyah), and retained close connections to Basrah even after he moved to central Arabia; and (4) Yaḥyá’s hadith is specifically transmitted by Basrans. The simplest explanation that would actually account for all of this converging evidence would be that Yaḥyá, towards the end of his life, upon learning of the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah in Isfahan, created this hadith and disseminated it to some Basran students. To argue otherwise is simply to ignore or disregard the unlikely convergence of all of these factors.

Part 7: al-ʾAwzāʿī and Yaḥyá as Co-Creators

If indeed Yaḥyá created his ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing Antichrist hadith during the reign of Marwān (c. 127-132/744-750), how would this impact the hypothesis in my original article that al-ʾAwzāʿī created his own ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing Antichrist hadith? Most of the original considerations remain unchanged: al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith clearly refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah; the ʿĪsawiyyah arose (c. 127-132/744-750) and rebelled (c. 136-158/754-775) during al-ʾAwzāʿī’s own lifetime (b. 88/706-707 or 93/711-712; d. 151/768, or 156/772-773, or 157/773-774); the more likely catalyst for the creation of such a hadith would have been the rebellion, which probably precludes the hadith’s deriving from any of al-ʾAwzāʿī’s cited sources; and there is evidence that the ʿĪsawiyyah spread to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s native Syria. The simplest explanation for all of this data would be that al-ʾAwzāʿī created his own hadith about the ʿĪsawiyyah and falsely ascribed it to an earlier source.

Of course, the chronological possibility remains that al-ʾAwzāʿī’s cited sources could have created the hadith as well: in one version of his hadith, he reportedly cited Ḥassān b. ʿAṭiyyah (Damascene; d. c. 130/747-748); in another version, he reportedly cited Rabīʿah b. ʾabī ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (Madinan; d. 136/753-754); and in yet another version, which can be positively traced back to al-ʾAwzāʿī, he cited ʾIsḥāq b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾabī Ṭalḥah (Madinan; d. 132/749-750 or 134/751-752). Thus, as in the preceding case of Yaḥyá, all of these putative sources lived unto the era of the rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah (c. 127-132/744-750) and could thus be responsible for this hadith instead, which is to say: it is possible that al-ʾAwzāʿī was simply the transmitter of a recent false creation, rather than the creator per se.

Unlike in Yaḥyá’s case, however, there is no special factor (i.e., an earlier CL) that pushes us to prefer the mere rise of the ʿĪsawiyyah over their rebellion as the catalyst for the hadith’s creation, or in other words: all else being equal, the rebellion of the ʿĪsawiyyah remains the more probable trigger behind al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith. This immediately removes Ḥassān, ʾIsḥāq, and Rabīʿah[122] as probable candidates for the hadith’s creator, leaving only al-ʾAwzāʿī. Moreover, in the case of Rabīʿah and ʾIsḥāq—both of whom were Madinan—in particular, there is a further reason to remove them from consideration: it seems far more likely that someone living in the Levant—a region with a substantial Jewish population that was linked to the Jewish communities of Persia[123]—would have heard of and cared about the ʿĪsawiyyah, versus someone living in out-of-the-way Madinah.

Indeed, we have evidence for the spread of the ʿĪsawiyyah to the Levant: according to the later Karaite Jewish writer ʾAbū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb al-Qirqisānī (fl. early 10th C. CE), in his coverage of ʾAbū ʿĪsá, “[there is] a group of his followers [still living] in Damascus, known as the ʿĪsūniyyah [sic].”[124] It is completely reasonable to suppose that the presence of the ʿĪsawiyyah in the Levant dates back to the movement’s initial rise in the mid-to-late 8th Century CE—after all, the Levant was home to large Jewish communities who were linked to the Persian Jewish communities in which the ʿĪsawiyyah erupted, as noted already. In other words, whilst there is no direct evidence of an ʿĪsawī presence in al-ʾAwzāʿī’s homeland during his lifetime, the evidence is still consistent with such a hypothesis, which is also expected in light of the interconnectedness of the relevant Jewish communities during this general time-period, not to mention the importance of the Holy Land for such messianic movements. To dismiss all of this as “speculation”[125] is simply to ignore the various considerations and indications in favour of a reasonable conclusion: that the ʿĪsawiyyah were probably already spreading to Jewish communities in the Levant during the movement’s heyday, which coincided with al-ʾAwzāʿī’s lifetime. As such, al-ʾAwzāʿī’s ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing hadith fits far better with—and is much more likely to be the product of—the Levantine religious milieu of the mid-to-late 8th Century CE, as opposed to that of early Madinah. We thus have another strong reason to prefer al-ʾAwzāʿī as the hadith’s creator, versus some earlier Madinan source.

It thus seems probable that both al-ʾAwzāʿī and Yaḥyá falsely ascribed their extant hadiths to their respective sources—sources who lived prior to the rise and/or rebellion of the ʿĪsawiyyah, and/or who hailed from regions that are less fitting as contexts of origin for the material. In this sense, al-ʾAwzāʿī and Yaḥyá are the most likely candidates for the creators of their hadiths.[126] However, two important questions remain. Firstly: did al-ʾAwzāʿī and Yaḥyá create the matns of their respective hadiths ex-nihilo (i.e., from scratch) or ex-materia (i.e., repackaging existing Hadith material)? Secondly: what is the textual relationship between the matns of these two hadiths?

In answer to the first question (in a similar vein to my original blog article), it seems plausible, if not probable, that both Yaḥyá and al-ʾAwzāʿī drew upon and reworked existing eschatological material to fashion their respective matns: the updating of prophecies to address new events is ubiquitous across the history of eschatology, as is the reuse and adaption of topoi in the creation of texts.[127] This sort of thing has also been widely observed across the Hadith corpus,[128] and can be readily observed in eschatological Hadith in particular.[129] There are signs of a similar process at play with Yaḥyá and al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadiths in particular:

- The statement, “verily, God / your Lord / my Lord is not one-eyed” (ʾinna allāh / rabba-kum / rabbī laysa bi-ʾaʿwar), in relation to the Antichrist, present in Yaḥyá’s hadith, can be found in numerous other hadiths from multiple regions, including from Basrah.[130]

- The proposition that the Antichrist will not be able enter Madinah, present in Yaḥyá’s hadith, can be found in another hadith with a Basran isnad.[131]

- The proposition that Jesus will remain on Earth for forty years after slaying the Antichrist, present in Yaḥyá’s hadith, can be found in other hadiths with Basran isnads.[132]

- The proposition that the Antichrist will be followed by 70,000 Muslims wearing Persian garments (ʿalay-him al-sījān), which is similar in content to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith, can be found in another hadith with a Basran isnad.[133]

- The proposition that the Antichrist will be followed by 70,000 people wearing Persian garments (ʿalay-him al-sījān), most of whom will be Jews and women, which is similar in content to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith, can be found in another hadith with a Basran isnad.[134]

- The proposition that the Antichrist will be followed by 80,000 people from Ḵūz and Kirmān wearing Persian garments (al-ṭayālisah), which is broadly similar to the content of al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith, can be found in another hadith with an Iraqo-Madinan isnad.[135]

Of course, each of these related hadiths has to be subjected to its own ICMA before the probable relationships therebetween can be established with confidence, and some of them are plausibly inspired or influenced Yaḥyá and al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadiths instead; but it is at least highly plausible that both Yaḥyá and al-ʾAwzāʿī draw upon existing elements in early Islamic eschatological discourse—associated above all with Basrah—to fashion their own ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing Antichrist hadiths.

The dense Basran association with this material tentatively suggests that al-ʾAwzāʿī was influenced by material flowing therefrom, including plausibly Yaḥyá’s hadith, or perhaps something similar to the short statement attributed to Yaḥyá by ʿAbd al-Razzāq, which is actually closer to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith. In light of the fact that al-ʾAwzāʿī only seems to have studied with Yaḥyá prior to the rise and rebellion of the ʿĪsawiyyah (i.e., prior to the reign of Marwān), a direct transmission between the two is precluded in this instance; but it is still plausible that he encountered a variant of Yaḥyá’s material that travelled out of Basrah and into his own Syrian environment, along with other Basran “Antichrist” material. Ultimately, however, the exact provenance of the material that al-ʾAwzāʿī incorporated into his own ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing hadith—which he falsely ascribed to a Madinan predecessor of his—cannot be known with certainty.

In sum: (1) al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith clearly refers to the ʿĪsawiyyah; (2) the ʿĪsawiyyah arose and rebelled during al-ʾAwzāʿī’s own lifetime; (3) the more likely catalyst for the creation of such a hadith would have been the rebellion of the ʿĪsawiyyah; (4) al-ʾAwzāʿī lived at the same time as the ʿĪsawī rebellion and in a region that was likely buzzing with news thereof, if not a region infiltrated by the ʿĪsawiyyah themselves, making al-ʾAwzāʿī an ideal candidate for being the hadith’s creator; (5) al-ʾAwzāʿī’s cited sources lived unexpectedly early, or in a less expected location, to create such a hadith; (6) al-ʾAwzāʿī is thus the most likely candidate for being the hadith’s creator. Furthermore: (7) both Yaḥyá and al-ʾAwzāʿī plausibly reworked existing eschatological material—associated above all with the former’s native Basrah—to produce their ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing hadiths; and (8) al-ʾAwzāʿī plausibly reworked a version of Yaḥyá’s ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing material to produce his own ʿĪsawiyyah-referencing hadith.

Part 8: An Alternative Chronology of the ʿĪsawiyyah?

The preceding analysis has assumed the correctness of the chronology of the rise and rebellion of the ʿĪsawiyyah recorded by Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-Karīm al-Šahrastānī (d. 548/1153),[136] which has been variously defended not just by Sean Anthony,[137] but also by Israel Friedländer,[138] Steven Wasserstrom,[139] and Halil İbrahim Bulut.[140] There is however an alternative chronology, recorded in al-Qirqisānī’s account of ʾAbū ʿĪsá: “he made his appearance during the days of ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān, and it has been mentioned that he sought to rebel against the government.”[141] In other words, according to al-Qirqisānī’s report, ʾAbū ʿĪsá arose and rebelled during the reign of ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān (c. 65-86/685-705), in the late 1st Century AH / at the turn of the 8th Century CE.[142] This chronology was accepted by Shelomo Goitein[143] and other older scholars,[144] although it is now clearly the minority position in modern scholarship.