Ignaz Goldziher famously argued that Hadith largely reflect not the life and times of the Prophet and his contemporaries, but rather, the historical contexts and interests of later generations of Muslims:

Closer acquaintance with the vast stock of ḥadīths induces sceptical caution rather than optimistic trust regarding the material brought together in the carefully compiled collections. We are unlikely to have even as much confidence as Dozy regarding a large part of the ḥadīth, but will probably consider by far the greater part of it as the result of the religious, historical and social development of Islam during the first two centuries.

The ḥadīth will not serve as a document for the history of the infancy of Islam, but rather as a reflection of the tendencies which appeared in the community during the maturer stages of its development. It contains invaluable evidence for the evolution of Islam during the years when it was forming itself into an organized whole from powerful mutually opposed forces.[1]

Since Goldziher’s time, a succession of scholars—including Joseph Schacht, Gautier Juynboll, Harald Motzki, and Gregor Schoeler—have proposed and refined isnad-critical methods of dating hadith according to the “common link” (henceforth, CL) that often appears in the isnads that support them. Although some scholars (above all, Michael Cook) have questioned whether CLs are actually the product of successive borrowings and parallel false ascriptions (“the spread of isnāds”),[2] others (above all, Motzki and Schoeler) have argued that CLs were merely the first systematic collectors and disseminators of Hadith rather than the creators thereof,[3] and still others have argued that CLs can be identified as the outright creators of their hadiths.[4] At the very least, most scholars agree that the CLs were at minimum the formulators of the underlying, extant wordings of their hadiths (i.e., at least to some degree refashioning existing material).[5] Apropos this debate, Juynboll has argued that, in some cases, the content of hadiths can be correlated with the particular interests or historical contexts of their CLs, which makes it likely that the CLs in question created—or recreated—the hadiths in question:

There are still a great number of transmitters dealt with in the rijāl works whose reputations are described as being without any blemish, even if on the basis of data adduced from elsewhere it can be proven with undeniable evidence that the material in whose transmission they are said to have been instrumental bears sure signs of fabrication, a fabrication which in all likelihood dates from their lifetimes.[6]

The easiest cases in which such connections can be established are overtly anachronistic hadiths (i.e., hadiths that describe phenomena in Islamic history that occurred or arose after the time of the putative sources of thereof),[7] including prophetic hadiths (i.e., hadiths purporting to record a prophecy from the Prophet or some other early figure concerning later events in Islamic history).[8] Of course, such anachronisms are often—though not always—explained away in traditional-religious and apologetical contexts as the product of genuine (God-given) prophecy,[9] but this is a poor explanation, for two reasons. Firstly, prior probability overwhelmingly favours ex-eventu creation as the explanation for such texts throughout history in general.[10] Secondly, the putative prophecies in question, whenever they are actually specific and unambiguous, always refer to phenomena that arose or occurred before Hadith were codified (i.e., canonised or otherwise preserved in extant written collections, generally from around 800 CE onwards).[11] In other words, it just so happens that Hadith only seem to clearly prophesy about times when Hadith could still be created (pre-codification), but not times when Hadith could no longer be created (post-codification).[12] Or, to put it even more simply: Hadith only seem to make accurate predictions up until the point when they were recorded in written collections. This is exactly what the ‘ex-eventu creation’ hypothesis predicts, as opposed to the ‘genuine prophecy’ hypothesis (which generates no such prediction).[13]

In short, if we find that a given hadith can be traced back to a CL, and if we further discover that the content of the hadith exactly matches the interests or context of that specific individual, that is a strong reason to think that the CL did not merely reword and disseminate the hadith, but more actively created or refashioned the idea or content therein.

An interesting test case for this methodological principle is the following Prophetical—and prophetic—hadith, recorded in the Ṣaḥīḥ of Muslim:

Manṣūr b. ʾabī Muzāḥim related to us: “Yaḥyá b. Ḥamzah related to us, from al-ʾAwzāʿī, from ʾIsḥāq b. ʿAbd Allāh, from his uncle ʾAnas b. Mālik, that the Messenger of God said: “From amongst the Jews of Isfahan, 70,000 will follow the Antichrist (al-dajjāl), wearing [Persian] head coverings (ʿalay-him al-ṭayālisah).””[14]

By subjecting this hadith—i.e., all extant versions thereof—to an isnad-cum-matn analysis, we can evaluate whether it ultimately derives from the underlying redaction of a CL; and by subjecting this inferable redaction in turn to a historical-critical analysis, we can evaluate whether—or to what extent—its content matches the particular interests or context of the CL. Finally, by further subjecting this hadith to a form-critical analysis and taking into account similar material, we can evaluate whether—or to what extent—the CL may have inherited or reworked earlier or common material into a particular iteration that served their interests or reflected their context.

An Isnad-Cum-Matn Analysis

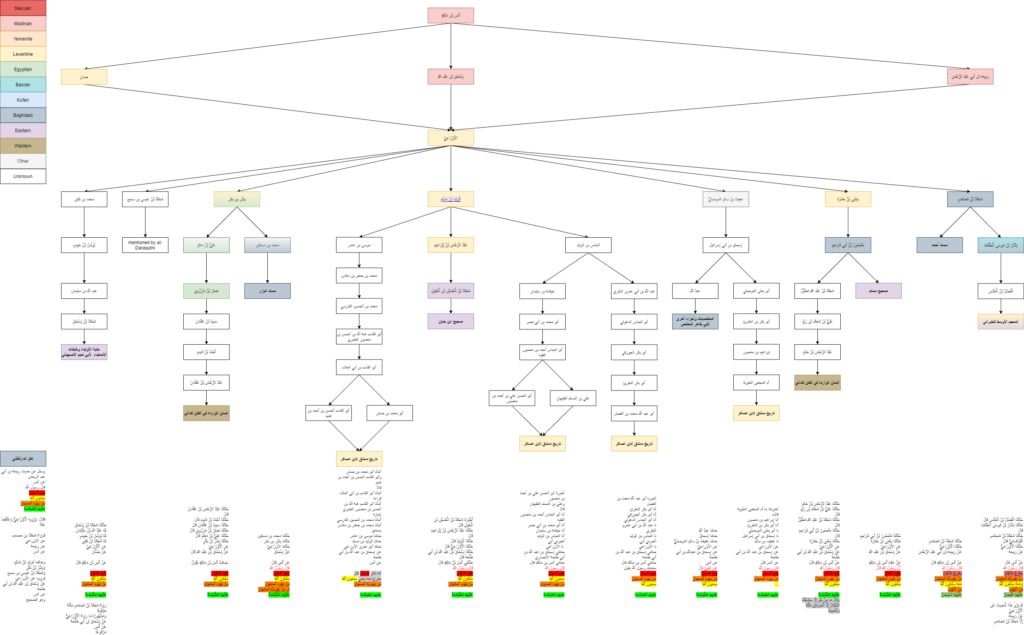

The CL of this hadith is the 8th-Century CE Syrian traditionist ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʿAmr al-ʾAwzāʿī, upon whom several PCLs converge in their respective (often distinctive) ascriptions: the Baghdadian traditionist Muḥammad b. Muṣʿab (fl. late 8th C. CE)[15]; the Syrian traditionist al-Walīd b. Muslim (d. 195/810)[16]; the Syro-Egyptian traditionist Bišr b. Bakr (d. 250/864)[17]; the Baghdadian traditionist Manṣūr b. ʾabī Muzāḥim (d. 235/849-850), via the Syrian traditionist Yaḥyá b. Ḥamzah (d. 183/799-800)[18]; and the Marwazī traditionist ʾIsḥāq b. ʾabī ʾIsrāʾīl (d. 245-246/859-861), via the Mawṣilī traditionist ʿAfīf b. Sālim (d. 233/847-848).[19] Additionally, a SS reaches back to him via the Syro-Mopsuestian traditionist Muḥammad b. Kaṯīr (d. 216/831).[20]

However, there are numerous incongruities and contradictions in the matns ascribed to these PCLs (i.e., contaminations, interpolations, and/or errors), which makes the concrete reconstruction of specific or distinctive PCL redactions largely impossible.[21]

That said, the tradition as a whole—the particular set of elements and wordings therein—is still distinctive (i.e., internally more alike) in comparison with similar or related hadiths (to be discussed below), which correlates with the common ascription of this tradition to a CL. Consequently, it is reasonable to conclude that the hadith overall traces back to al-ʾAwzāʿī in Syria, and although the exact sequence of his original cannot be pinpointed, the gist remains clear: the Antichrist will be followed by 70,000 Isfahanian Jews, wearing Persian head coverings.[22]

There are some notable divergences in the isnad, however: the version ascribed via Ibn Kaṯīr has al-ʾAwzāʿī cite the junior Damascene Follower Ḥassān b. ʿAṭiyyah (d. c. 130/747-748), from the junior Madinan Companion ʾAnas b. Mālik (d. 91-93/709-712); Ibn Muṣʿab has him cite the Madinan muftī and Follower Rabīʿah b. ʾabī ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (d. 136/753-754), from ʾAnas; and al-Walīd, Bišr, Manṣūr, and ʾIsḥāq all have him cite the Madinan Follower ʾIsḥāq b. ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾabī Ṭalḥah (d. 132/749-750 or 134/751-752), from ʾAnas. Additionally, the transmission via Ibn Kaṯīr, one transmission from al-Walīd, and one transmission from Bišr all have ʾAnas being cited on his own authority (i.e., the hadith is mawqūf), where Ibn Muṣʿab, Manṣūr, ʾIsḥāq, the other transmission from Bišr, and the other transmissions from al-Walīd all have ʾAnas cite the Prophet (i.e., the hadith is marfūʿ). Based on the Criterion of Dissimilarity, the mawqūf version is certainly the original, whilst the marfūʿ is a later reformulation (whereby a statement initially ascribed to a Companion was ‘raised’ back to the Prophet).[23] Given that both versions are multiply-attested back to al-ʾAwzāʿī, it looks like the CL himself was responsible for this change, likely raising the hadith in successive retellings. (Of course, it is also likely that some contamination and/or synchronous raising occurred between his students and/or later tradents, given that unraised and raised versions are sometimes attributed to the same PCLs.) By contrast, in the later segment of the SS that precedes al-ʾAwzāʿī, only the citation of ʾIsḥāq is multiply-transmitted from al-ʾAwzāʿī, whereas the alternative citations of Ḥassān and Rabīʿah are respectively confined to a SS and a single PCL. In these cases, al-ʾAwzāʿī’s students or later tradents are plausibly responsible for the variation.

For the proto-Sunnī Hadith critics, only one version was correct: al-ʾAwzāʿī transmitted from ʾIsḥāq, from ʾAnas, from the Prophet. Thus, Ibn Muṣʿab’s version (al-ʾAwzāʿī—Rabīʿah—ʾAnas—Prophet) was flagged by al-Ṭabarānī as suspect,[24] whilst the version of Manṣūr, ʾIsḥāq, et al. (al-ʾAwzāʿī—ʾIsḥāq—ʾAnas—Prophet) is identified by ʾAbū Nuʿaym as “the [hadith’s] well-known version” (mašhūru-hu),[25] and by al-Dāraquṭnī as “the correct version” (al-ṣaḥīḥ).[26] Finally, as noted at the outset, Muslim included this version in his Ṣaḥīḥ.[27]

In short, the hadith prophesying that 70,000 Jews in Isfahan wearing Persian clothes would follow the Antichrist can be traced back to the CL al-ʾAwzāʿī, who originally ascribed it via the Follower ʾIsḥāq b. ʿAbd Allāh back to the Companion ʾAnas b. Mālik, but later raised it all the way back to the Prophet. The Follower in the pre-CL SS was altered in some transmissions (plausibly after al-ʾAwzāʿī), resulting in the spread of several different versions. Of these versions, only al-ʾAwzāʿī’s raised version attained canonical status, being deemed ‘sound’ (ṣaḥīḥ) by the later Hadith critics.

A Historical-Critical Analysis

This hadith undoubtedly refers to the ʿĪsāwiyyah, a Jewish sect and rebellion that erupted in Isfahan during the 8th Century CE, led by the prophet or messiah ʾAbū ʿĪsá al-ʾIṣfahānī. This is a perfect match: ʾAbū ʿĪsá was (to any outsider) a false messiah or antichrist, which corresponds with the Antichrist in the hadith; he was supported by a base of Persian Jews, which corresponds to the Jews wearing Persian garments in the hadith; and he and his followers arose in Isfahan, which corresponds to the hadith’s specification of Isfahanian Jews.[28] Since genuine prophecy is vanishingly unlikely (see above), and since it also seems unlikely that the ʿĪsāwiyyah would have modelled themselves upon a prophecy in which they are the villains, it follows that the hadith must have been modelled upon the ʿĪsāwiyyah, or in other words: this ṣaḥīḥ hadith is very likely a false creation, a polemical reaction to a Jewish sect that rebelled against the caliphal state. However, a solid terminus a quo for the creation of the hadith is tricky, given that mediaeval sources are inconsistent regarding the exact period in which the ʿĪsāwiyyah arose: one places their origin and rebellion in the reign of ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān (r. 685-705 CE), and another places their origin in the reign of Marwān II (r. 744-750 CE) and their rebellion in the reign of the second Abbasid caliph al-Manṣūr (r. 754-775 CE).[29] If the first dating is adopted, then it is possible that anyone in the isnad up until al-ʾAwzāʿī was responsible for creating this hadith, except of course the Prophet: it could have been ʾAnas, reacting to a new sectarian and rebel menace in extreme old age; it could have been ʾIsḥāq, Ḥassān, or Rabīʿah, either as young men directly responding to the rebellion, or in reflection on the events of their youth; it could have been al-ʾAwzāʿī, based on tales of events that occurred shortly before his birth; or it could have been someone else, who was since dropped from the isnad by al-ʾAwzāʿī or a predecessor—in which case, someone between ʾAnas and al-ʾAwzāʿī engaged in the worst kind of tadlīs (by omitting a kaḏḏāb), or even engaged in sariqah (by taking someone else’s hadith and giving it a new isnad). And of course, if either Ḥassān or Rabīʿah were the creators of this hadith, then al-ʾAwzāʿī engaged in a secondary interpolation in his isnad by replacing them with ʾIsḥāq in most versions of the hadith that he disseminated to his students. Thus, in the best-case scenario, someone in this isnad committed the worst kind of tadlīs; and in the worst-case scenario, someone committed sariqah or kaḏib—at least according to the later categories of the Hadith critics.

However, Sean Anthony has argued—on the basis of an evaluation of additional sources, and the relationship between the ʿĪsāwiyyah and a preceding Jewish movement—that the later dating is more likely to be correct: the ʿĪsāwiyyah probably arose after 744 CE and rebelled after 754 CE.[30] This creates a much later terminus a quo for our hadith—more likely 754 ff. CE than 744 ff. CE, since the rebellion of this messianic sect in Isfahan seems more likely to have attracted the polemical attention of Muslims in other regions than their mere appearance (i.e., alongside any other number of small religious movements and sects under the caliphate). This leaves only al-ʾAwzāʿī—who was born in 88/706-707, or 93/711-712, and died in 151/768, or 156/772-773, or 157/773-774—as a genuine transmitter of this hadith, which in turn leaves us with only three plausible scenarios for its creation: al-ʾAwzāʿī borrowed the hadith from a contemporary who created it, then suppressed the creator, whilst otherwise retaining their isnad (i.e., the worst kind of tadlīs); or he took the hadith from a contemporary who created it and gave it a new isnad (i.e., sariqah); or he created the hadith himself (i.e., kaḏib). The last scenario is the simplest (i.e., the most parsimonious), and thus the most likely, all else being equal.

Moreover, it just so happens that a later source explicitly mentions a population of ʿĪsāwiyyah still lingering in Damascus, which is consistent with the movement’s having gained a following amongst Jews in Syria when it first came to prominence (i.e., during the middle of the 8th Century CE). Thus, according to Israel Friedlaender, “it seems that the ʿĪsawiyya, those who continued to expect Abū ʿĪsa’s return, left Ispahan and migrated to Damascus, where Ḳirḳisānī, two centuries later, still found remnants of them to the number of twenty or thirty souls”.[31] Furthermore: “It is natural to assume that, when Abū ʿĪsa had been defeated and killed, his adherents, at least some of them, fled to Syria. That there were relations between Syria and Persia is shown by such names of Persian-Jewish sectarians as Baʿlbekki and Ramlī.”[32]

This would greatly help to explain why the al-ʾAwzāʿī created the hadith in the first place: it was probably a reaction not just to the rebellion of ʾAbū ʿĪsá in distant Isfahan, but to the local spread of his messianic movement. In short, we have a perfect match between the content of this hadith, on the one hand, and the specific interests and context of its CL, on the other.

Excursus: ʿIlm al-Rijāl and al-ʾAwzāʿī

All of this is despite the fact that al-ʾAwzāʿī was “reliable” (ṯiqah), according to both Muḥammad b. Saʿd and al-ʿIjlī[33]; “amongst the best of people” (min ḵiyār al-nās), according to al-ʿIjlī[34]; “a leading scholar whose example is emulated” (ʾimām yuqtadá bi-hi), according to a report from Mālik[35]; “the best of the people of his time” (ʾafḍal ʾahl zamāni-hi), according to al-Ḵuraybī[36]; and “[one] of the scholars who were Hadith critics” (min al-ʿulamāʾ al-jahābiḏah al-nuqqād), according to Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim.[37] One of the few blips on his record is the report from Ibn Ḥanbal that “the Hadith of al-ʾAwzāʿī from Yaḥyá are muddled (muḍṭarib),”[38] along with the following:

ʾIbrāhīm al-Ḥarbī said: “I asked ʾAḥmad b. Ḥanbal: “What do you say about Mālik?” He said: “Sound Hadith, but weak jurisprudence (ḥadīṯ ṣaḥīḥ wa-raʾy ḍaʿīf).” I said: “And al-ʾAwzāʿī?” He said: “Weak Hadith and weak jurisprudence (ḥadīṯ ḍaʿīf wa-raʾy ḍaʿīf).” I said: “And al-Šāfiʿī?” He said: “Sound hadith and sound jurisprudence (ḥadīṯ ṣaḥīḥ wa-raʾy ṣaḥīḥ).” I said: “And so-and-so?” He said: “No jurisprudence, nor Hadith.””[39]

However, al-Ḏahabī hastened to clarify:

He meant that al-ʾAwzāʿī’s Hadith are weak due to his having relied in his argumentation (yaḥtajju) upon the Follower hadiths (bi-al-maqāṭīʿ) and the discontinuously-transmitted hadiths (wa-bi-marāsīl) of the People of the Levant, in which there is weakness (ḍaʿf)—not that the imam himself was weak.[40]

Thus, al-ʾAwzāʿī is cited literally hundreds of times within the Sunnite canon (including the Ṣaḥīḥayn), and the specific hadith in question was explicitly accepted and designated as ṣaḥīḥ, despite its being an obvious fabrication (at least to modern eyes).

A Form-Critical Analysis

However, it is worth noting that the hadith was not necessarily fabricated whole-cloth, meaning, it may have incorporated or been constructed out of some elements or tropes that were already in circulation. After all, the elements of the Jewish followers, the number 70,000, ʿalay-him al-ṭayālisah, and ʿalay-him al-sījān all appear in various combinations in other hadiths about the Antichrist:

- ʿAbd al-Razzāq transmitted—via a Basran SS unto the Companion ʾAbū Saʿīd al-Ḵudrī—from the Prophet the following statement: “From amongst my community, 70,000 will follow the Antichrist, wearing sījān.”[41]

- Ibn ʾabī Šaybah transmitted—via a Madinan SS—from the Companion ʾAbū Hurayrah, on his own authority, the following statement: “The Antichrist will come from the furnace of Karmān [sic], accompanied by 80,000, wearing ṭayālisah. They will wear fur shoes, and it will be as if their faces are hammered shields.”[42]

- al-Ḥasan b. Rašīq transmitted—via a Madinan SS unto ʾAbū Hurayrah—from the Prophet the following statement: “The Antichrist will emerge upon a moon-white donkey, between whose ears is [the distance of] 70 spans. 70,000 Jews will accompany him, wearing green ṭayālisah, until they descend the hill of ʾAbū al-Ḥamrāʾ.”[43]

- Ibn ʾabī Šaybah transmitted—via a Basran SS unto the Companion ʿUṯmān b. ʾabī al-ʿĀṣ—from the Prophet a lengthy narration that includes the following statement concerning the Antichrist: “70,000 will accompany him, wearing sījān, and most of his followers will be Jews and women.”[44]

- Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād transmitted—via a munqaṭiʿ Syrian SS—from the Follower Kaʿb al-ʾAḥbār, on his own authority, a lengthy narration that includes the following statement concerning the Antichrist: “Those [who follow him] will be 40,000 (and some of the scholars say: 70,000), and nations will come, and he will seek their aid against the People of Syria, and they will assent to him. Then all the Jews will be gathered to him, then his Eastern band vanguard will travel in the direction of Syria, accompanied by the bedouins of Jadīs wearing al-ṭayālisah.”[45]

Of course, the direction of influence in such instances could be reversed: since al-ʾAwzāʿī’s version can be securely established earlier than the rest (i.e., due to the corroborating transmissions unto him), it is possible that all of these other hadiths were contaminated by his original formulation. This seems even more likely in the case of the following reports, which are even more closely related to al-ʾAwzāʿī’s version:

- al-Ṭabarānī transmitted—via a Basro-Kufan SS unto the Companion Fāṭimah bt. Qays—from the Prophet a lengthy narration that includes the following statement concerning the Antichrist: “He will depart from a city called Isfahan, [specifically] from one of its villages called Rustaqbāḏ. He will depart when 70,000, wearing al-sījān, depart under his leadership.”[46]

- al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī transmitted—via a Basro-Yamāmī SS unto ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar—from the Prophet a lengthy narration that includes the statement: “The Antichrist will emerge from amongst the Jews of Isfahan.”[47]

- ʿAbd al-Razzāq transmitted, from his Basran master Maʿmar, from the latter’s Basro-Yamāmī master Yaḥyá b. ʾabī Kaṯīr (d. 129/746-747), the following short statement (i.e., on his own authority): “The majority of those who follow the Antichrist will be the Jews of Isfahan.”[48]

The first two reports are uncorroborated and cannot be traced back as early as al-ʾAwzāʿī and his version; in conjunction with the hadith’s snugly matching al-ʾAwzāʿī’s context, this is a strong reason to regard them as contaminated by the latter. More intriguing is the ascription to Yaḥyá, who happens to have been one of al-ʾAwzāʿī’s teachers. However, this ascription to Yaḥyá is chronologically unlikely (since he died before the ʿĪsāwiyyah rebelled), and even its ascription to Maʿmar is uncorroborated, all of which is consistent with its having been derived—perhaps through error—from al-ʾAwzāʿī’s original formulation. Still, the lack of an earlier ascription for Yaḥyá’s statement (i.e., its not being an ascription to a Companion or the Prophet) makes it seem more archaic than al-ʾAwzāʿī’s version: were it not for the chronological incongruities (based on Anthony’s timeline), one might think that this hadith originated with a statement of Yaḥyá’s, which his student al-ʾAwzāʿī reformulated into an ascription to ʾAnas b. Mālik, which he subsequently raised all the way back to the Prophet. And, although I am not aware of the ʿĪsāwiyyah spreading in Basrah or al-Yamāmah (in contrast to Syria), there may have been strong links between Basrah and Isfahan—after all, it was the Basrans who conquered Isfahan during the Arab conquest of Persia.[49] Consequently, we could easily imagine an analogous Basran concern with the ʿĪsāwiyyah as well—hence, the seeming association between Basrah and most iterations of this material.

As it stands, however, the earliest securely-datable version of this material is al-ʾAwzāʿī’s, who also fits perfectly chronologically, and who also happens to have been based in a region where the ʿĪsāwiyyah specifically had a presence.

Conclusion

The hadith prophesying that 70,000 Jews in Isfahan wearing Persian clothes would follow the Antichrist is a prime candidate for being a hadith that was created by its CL. This hadith can be traced back to its CL al-ʾAwzāʿī, but no earlier. The hadith’s content clearly refers to the ʿĪsāwiyyah, a Jewish messianic movement that rebelled in Isfahan soon after 754 CE—this automatically precludes its being a genuine transmission from any of the pre-CL tradents or sources cited therefor, including ʾIsḥāq b. ʿAbd Allāh (d. 132/749-750 or 134/751-752), ʾAnas b. Mālik (d. 91-93/709-712), and the Prophet (d. 11/632). In other words, whilst this hadith can be traced back to al-ʾAwzāʿī via an isnad-cum-matn analysis, his ascription of the hadith back to an earlier source is falsified on historical-critical grounds. Moreover, in addition to broadly reflecting al-ʾAwzāʿī’s (default Islamic) censure of a messianic Jewish rebellion, it is probable that it reflects his more direct concerns, given the spread of the ʿĪsāwiyyah to his Syrian homeland during his heyday (i.e., the mid-to-late 8th Century CE). We thus have a perfect match between the CL’s interests and context, on the one hand, and a hadith that can be traced back to him but cannot be traced back to his alleged sources. It thus seems quite likely that al-ʾAwzāʿī himself created this hadith, as a polemical reaction to the rise of the ʿĪsāwiyyah and their spread to Syria. That said, a form-critical comparison of this hadith with others raises the possibility that al-ʾAwzāʿī constructed it from an existing pool of Antichrist-related material, although it is equally possible that these others were in fact contaminated by or borrowed from al-ʾAwzāʿī’s hadith. There is also a curious Basran association with most of these other hadiths, but this will have to await further research.

In short, it is likely that the hadith prophesying that 70,000 Jews in Isfahan wearing Persian clothes would follow the Antichrist was created by its CL, al-ʾAwzāʿī, despite his being judged to be “reliable” (ṯiqah), and his hadith’s being judged to be “sound” (ṣaḥīḥ), by later proto-Sunnī Hadith critics.

* * *

I owe special thanks to al-Firas, Qur’anic Islam, and Yet Another Student, for helping to clarify certain textual points.

[1] Ignaz Goldziher (ed. Samuel M. Stern and trans. Christa R. Barber & Samuel M. Stern), Muslim Studies, Volume 2 (Albany, USA: State University Press of New York, 1971), 19. Similarly, see David S. Margoliouth, ‘On Moslem Tradition’, The Moslem World, Volume 2, Number 2 (1912), 121; Joseph F. Schacht, The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1950), passim; Patricia Crone, Medieval Islamic Political Thought (Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 126, n. 3. For some specific examples, see Ehsan Roohi, ‘A Form-Critical Analysis of the al-Rajīʿ and Biʾr Maʿūna Stories: Tribal, Ideological, and Legal Incentives behind the Transmission of the Prophet’s Biography’, al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā, Volume 30 (2022), 280 ff.

[2] Michael A. Cook, Early Muslim Dogma: A Source-critical Study (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1981), ch. 11.

[3] Harald Motzki (trans. Marion H. Katz), The Origins of Islamic Jurisprudence: Meccan Fiqh before the Classical Schools (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2002 [originally published in 1991]), 25; id. (trans. Frank Griffel & Paul Hardy), ‘Whither Ḥadīth Studies?’, in Harald Motzki, Analysing Muslim Traditions: Studies in Legal, Exegetical and Maghāzī Ḥadīth (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010), 51; id. (trans. Sonja Adrianovska & Vivien Reid), ‘The Prophet and the Debtors. A Ḥadīth Analysis under Scrutiny’, in Harald Motzki, Analysing Muslim Traditions: Studies in Legal, Exegetical and Maghāzī Ḥadīth (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010), 133 ff.; id., ‘The Collection of the Qurʾān: A Reconsideration of Western Views in Light of Recent Methodological Developments’, Der Islam, Volume 78 (2001), 29-30; id. (trans. Sonja Adrianovska & Vivien Reid), ‘Al-Radd ʿAlā l-Radd: Concerning the Method of Ḥadīth Analysis’, in Harald Motzki, Analysing Muslim Traditions: Studies in Legal, Exegetical and Maghāzī Ḥadīth (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010), 210-214; Andreas Görke, ‘Eschatology, History, and the Common Link: A Study in Methodology’, in Herbert Berg (ed.), Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2003), 188 ff.; Motzki, ‘The Origins of Muslim Exegesis. A Debate’, in Harald Motzki, Analysing Muslim Traditions: Studies in Legal, Exegetical and Maghāzī Ḥadīth (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010), 240; id., Reconstruction of a Source of Ibn Isḥāq’s Life of the Prophet and Early Qurʾān Exegesis: A Study of Early Ibn ʿAbbās Traditions (Piscataway, USA: Gorgias Press, 2017), 73; etc.

[4] Schacht, Origins, passim, but esp. 158, 171-172; Gautier H. A. Juynboll, Muslim tradition: Studies in chronology, provenance and authorship of early ḥadīth (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 207, 217; id., ‘Some isnād-analytical methods illustrated on the basis of several woman-demeaning sayings from ḥadīth literature’, al-Qanṭara, Volume 10, Issue 2 (1989), 353; id., Encyclopedia of Canonical Ḥadīth (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2007), ix, xvii, xx-xxi.

[5] E.g., Juynboll, ‘Some isnād-analytical methods’, 353; id., ‘The Role of Muʿammarūn in the Early Development of the Isnād’, Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, Volume 81 (1991), 155; id., ‘Early Islamic society as reflected in its use of isnāds’, Le Muséon, Volume 107 (1994), 155; id. ‘(Re)Appraisal of Some Technical Terms in Ḥadīth Science’, Islamic Law and Society, Volume 8, Number 3 (2001), 306; Motzki (trans. Adrianovska & Reid), ‘The Prophet and the Debtors’, in Motzki, Analysing Muslim Traditions, 134; id., ‘The Collection of the Qurʾān’, 31; Görke, ‘Eschatology’, in Berg (ed.), Method and Theory, 190, 199; A. Kevin Reinhart, ‘Juynbolliana, Gradualism, the Big Bang, and Ḥadīth Study in the Twenty-First Century’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Volume 130, Number 3 (2010), 421, n. 20; Stijn Aerts, ‘“Pray with Your Leader”: A Proto-Sunni Quietist Tradition’, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Volume 136, Issue 1 (2016),36; Jens Schneiner, ‘Single Isnāds or Riwāyas? Quoted Books in Ibn ʿAsākir’s Tarjama of Tamīm al-Dārī’, Maurice A. Pomerantz & Aram A. Shahin (eds.), The Heritage of Arabo-Islamic Learning: Studies Presented to Wadad Kadi (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2016), 61.

[6] Juynboll, Muslim tradition, 73. In this initial formulation, Juynboll did not connect this concept to CLs specifically, but did so subsequently, as in ibid., 206 ff., and id., ‘(Re)Appraisal’, 310.

[7] E.g., Fred M. Donner, Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing (Princeton, USA: The Darwin Press, Inc., 1998), 39 ff. Also see Jonathan A. C. Brown, ‘How We Know Early Ḥadīth Critics Did Matn Criticism and Why It’s So Hard to Find’, Islamic Law and Society, Volume 15 (2008), 182: “As generations of Western scholars have demonstrated, even the revered Ṣaḥīḥayn are replete with anachronistic reports that grew out of the political, legal and sectarian feuds of the first two centuries of Islam.”

[8] See especially Michael A. Cook, ‘Eschatology and the Dating of Traditions’, Princeton Papers in Near Eastern Studies, Volume 1 (1992), 23-47, and also Andreas Görke, ‘Eschatology, History, and the Common Link: A Study in Methodology’, in Herbert Berg (ed.), Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2003),179-208.

[9] Goldziher (trans. Barber & Stern), Muslim Studies, II, 141. Cf. Brown, ‘How We Know Early Ḥadīth Critics Did Matn Criticism’, on some exceptions.

[10] E.g., Cook, ‘Eschatology’, 25-26, along with 40, n. 21: “The theory I expound here is simply the way any modern scholar goes about dating an eschatological text. It is, however, particularly associated with the studies of Paul Alexander in the field of Byzantine apocalyptic.” More generally, on the overwhelming prior probability that accounts of the supernatural are explained by some kind of false creation rather than by their actually having occurred, see Richard C. Carrier, Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus (Amherst, USA: Prometheus Books, 2012), 114 ff.; Arif Ahmed, ‘Hume and the Independent Witnesses’, Mind, Volume 124, Issue 496 (2015), 1013-1044; id. & Richard C. Carrier, ‘Miracles: Atheism’, in Joseph W. Koterski & Graham Oppy (eds.), Theism and Atheism: Opposing Arguments in Philosophy (Farmington Hills, USA: Macmillan Reference USA, 2019), 211-226.

[11] For example, the well-known references to: caliphs and the caliphate; the fates of Muḥammad’s closest Companions; the Sasanid queens who arose during the period of instability following the Byzantine-Sasanid War; the four Rightly-Guided Caliphs; the Ḵawārij; the Qadariyyah; and the ʿĪsāwiyyah (discussed below). By contrast, hadiths that are claimed—invariably in traditional or apologetical contexts—to be references to later phenomena are suspiciously (1) extremely vague and (2) only convincingly relatable to later phenomena in the eyes of those with the relevant confessional or faith commitments. For example, consider the following prophecy from a canonical hadith: “…you will see barefoot (al-ḥufāh), naked (al-ʿurāh), destitute (al-ʿālah) shepherds (riʿāʾ al-šāʾ) arrogantly competing with each other in the construction [of great buildings] (yataṭāwalūna fī al-bunyān)…” This only seems like a clear reference to the modern Gulf States to some of the pious; for everyone else, it seems completely vague and could match any instance of pastoralists or bedouins—or people from such backgrounds—gaining power and engaging in great building projects in Islamic history. Alternatively, it can be reasonably understood as simply an iteration of the ubiquitous eschatological theme of the reversal of the natural order, or the occurrence of strange and unexpected things, during the End Times—thus, poor pastoralists, who normally do not have power and engage in great building projects, will gain power and engage in great building projects.

A seemingly more concrete example is the prophecy of the Muslim conquest of Constantinople, which is now taken by some Muslims to refer to the Ottoman conquest in 1453. However, putting aside the fact that most of the relevant hadiths link this conquest to the onset of the End Times (which militates against their being references to 1453, since the End Times did not immediately commence thereafter), all of these hadiths are completely vague, without any references to Turks, cannons, 1453, etc. (That said, given the Avar assaults against Constantinople in 619 and 626 CE, it would actually not be completely unexpected to find prophecies created soon after referring to a “Turkish” (i.e., Central Asian nomad) conquest of Constantinople.) All of this is compounded by the fact that there are much earlier events that such hadiths are plausibly referring or reacting to: the repeated Umayyad-led Arab attempts to conquer Constantinople during the 1st Islamic Century (i.e., during the reigns of ʿUṯmān, Muʿāwiyah, and Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Malik).

[12] E.g., the failure of miḥnah-inspired hadiths—created during the era of systematic transmission and rigorous scholarship—to gain traction; see Johann W. Fück (trans. Merlin L. Swartz), ‘The Role of Traditionalism in Islam’, in Merlin L. Swartz (ed.), Studies on Islam (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1981), 108-109.

[13] This argument has been notably articulated by Behnam Sadeghi in a forthcoming monograph.

[14] Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj al-Naysābūrī (ed. Naẓar b. Muḥammad al-Fāryābī), Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 2 vols. in 1 (Riyadh, KSA: Dār Ṭaybah, 2006), p. 1349, # 2944.

[15] ʾAḥmad b. Ḥanbal (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ & ʿĀdil Muršid), Musnad, vol. 21 (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, n. d.), pp. 55-56, # 13344; Sulaymān b. ʾAḥmad al-Ṭabarānī (ed. Ṭāriq b. ʿIwaḍ Allāh b. Muḥammad & ʿAbd al-Muḥsin b. ʾIbrāhīm al-Ḥusaynī), al-Muʿjam al-ʾAwsaṭ, vol. 5 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār al-Ḥaramayn, 1995), p. 156, # 4930. These transmissions via Ibn Muṣʿab share a matn that differs markedly from the rest, and also a difference in the isnad preceding al-ʾAwzāʿī.

[16] Muḥammad b. Ḥibbān al-Bustī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ), al-ʾIḥsān fī Tartīb Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān, vol. 15 (Beirut, Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1991), p. 209, # 6798; ʿAlī b. al-Ḥasan b. ʿAsākir (ed. ʿUmar b. Ḡaramah al-ʿAmrawī), Taʾrīḵ Madīnat Dimašq, vol. 6 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Fikr, 1995), p. 31; ibid., XXVII, p. 167; ibid., LII, pp. 359-360. There are serious divergences between these transmissions from al-Walīd, but two of them (the version of Ibn Ḥibbān and one of Ibn ʿAsākir’s) are identical in sequence and wording, although this is shared by the transmissions from Bišr and Ibn Kaṯīr (although the latter has a key difference in the isnad).

[17] ʾAḥmad b. ʿAmr al-Bazzār (ed. ʿĀdil b. Saʿd et al.), Musnad, vol. 13 (Madinah, KSA: Maktabat al-ʿUlūm wa-al-Ḥukm, 2003), pp. 73-74, # 6416; ʿUṯmān b. Saʿīd al-Dānī (ed. Riḍāʾ Allāh b. Muḥammad ʾIdrīs al-Mubārakbūrī), al-Sunnah al-Wāridah fī al-Fitan wa-Ḡawāʾili-hā wa-Sāʿah wa-ʾAšrāṭi-hā, vol. 6 (Riyadh, KSA: Dār al-ʿĀṣimah, 1416 AH), p. 1157, # 630. These transmissions via Bišr share the same sequence and an identical wording in their matn (bar an addition in the version of al-Bazzār), although the same sequence and wording also appears in the transmissions from al-Walīd and Ibn Kaṯīr (although again, the latter has a key difference in the isnad).

[18] Muslim (ed. Fāryābī), Ṣaḥīḥ, II, p. 1349, # 2944; Dānī (ed. Mubārakbūrī), al-Sunnah al-Wāridah, VI, pp. 1157-1158, # 631. These transmissions via Manṣūr share the same sequence and an identical wording in their matn (bar an addition in the version of al-Dānī), although the same sequence and wording also appears in the transmissions from ʾIsḥāq.

[19] Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Muḵalliṣ (ed. Nabīl Saʿd al-Dīn Jarrār), al-Muḵalliṣiyyāt wa-ʾAjzāʾ ʾUḵrá, vol. 1 (Qatar: Wizārat al-ʾAwqāt wa-al-Šuʾūn al-ʾIslāmiyyah, 2008), p. 463, # 840; Ibn ʿAsākir (ed. ʿAmrawī), Taʾrīḵ Madīnat Dimašq, XXVII, p. 167. These transmissions via ʾIsḥāq share the same sequence and an identical wording in their matn (bar an omission in the version of Ibn ʿAsākir), although the same sequence and wording also appears in the transmissions from Manṣūr.

[20] ʾAbū Nuʿaym ʾAḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-ʾIṣfahānī, Ḥilyat al-ʾAwliyāʾ wa-Ṭabaqāt al-ʾAṣfiyāʾ, vol. 6 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār al-Fikr, 1996), p. 77, with a difference in the isnad preceding al-ʾAwzāʿī.

[21] See the examples given in the preceding footnotes.

[22] For the perceived Judaeo-Persian origin of the ṭaylasān, see Judith Kindinger, ‘Bidʿa or sunna: The ṭaylasān as a Contested Garment in the Mamlūk Period (Discussions between al-Suyūṭī and Others)’, in Antonella Ghersetti (ed.), Al-Suyūṭī, a Polymath of the Mamlūk Period: Proceedings of the themed day of the First Conference of the School of Mamlūk Studies (Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, June 23, 2014) (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2016), 74-75.

[23] Joseph F. Schacht, ‘A Revaluation of Islamic Traditions’, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Number 2 (1949), 147; id., Origins, 156-157, 165; Cook, Early Muslim Dogma, 108; Patricia Crone, Roman, provincial and Islamic law: The origins of the Islamic patronate (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 29; Juynboll, ‘Some isnād-analytical methods’, 368-370; id., ‘Some notes on Islam’s first fuqahāʾ distilled from early ḥadīth literature’, Arabica, Volume 39 (1992), 300; Cook, ‘Eschatology’, 24; Christopher Melchert, ‘Basra and Kufa as the Earliest Centers of Islamic Legal Controversy’, in Behnam Sadeghi, Asad Q. Ahmed, Adam Silverstein, & Robert G. Hoyland (eds.), Islamic Cultures, Islamic Contexts: Essays in Honor of Professor Patricia Crone (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2015), 178.

[24] Ṭabarānī (ed. Ṭāriq & Ḥusaynī), al-Muʿjam al-ʾAwsaṭ, V, p. 156, # 4930: “No one except for Muḥammad b. Muṣʿab transmitted this hadith from al-ʾAwzāʿī, from Rabīʿah.”

[25] ʾAbū Nuʿaym, Ḥilyah, VI, p. 77.

[26] ʿAlī b. ʿUmar al-Dāraquṭnī, al-ʿIlal, vol. 12 (Dammam, KSA: Dār Ibn al-Jawzī, 1427 AH), p. 82, # 2447.

[27] Additionally, in light of the contention that Muslim placed his most reliable hadiths at the beginnings of their respective ʾabwāb, and the least reliable at the ends (e.g., Juynboll, ‘(Re)Appraisal’, 316), it is worth noting that the hadith under consideration is located at the very beginning of Muslim’s bāb fī baqiyyah min ʾaḥādīṯ al-dajjāl. That said, the extant chapter divisions and headings in the Ṣaḥīḥ were placed therein by later scholars, so this current placement may not be decisive.

[28] Unsurprisingly, others have made this connection already, e.g., Steven M. Wasserstrom, ‘The ʿĪsāwiyya Revisited’, Studia Islamica, Number 75 (1992), 68.

[29] Sean W. Anthony, ‘Who was the Shepherd of Damascus? The Enigma of Jewish and Messianist Responses to the Islamic Conquests in Marwānid Syria and Mesopotamia’, in Paul M. Cobb (ed.), The Lineaments of Islam: Studies in Honor of Fred McGraw Donner (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2012), 43.

[30] Ibid., 45 ff., 54.

[31] Israel Friedlaender, ‘Jewish-Arabic Studies’, The Jewish Quarterly Review, Volume 3 (1912-1913), 268-269. Also see Anthony, ‘Who was the Shepherd of Damascus?’, in Cobb (ed.), The Lineaments of Islam, 42.

[32] Friedlaender, ‘Jewish-Arabic Studies’, 269, n. 331.

[33] Muḥammad b. ʾAḥmad al-Ḏahabī (ed. Šuʿayb al-ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar ʾAʿlām al-Nubalāʾ, vol. 7, 2nd ed. (Beirut Lebanon: Muʾassasat al-Risālah, 1982), p. 109; ʾAḥmad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿIjlī (ed. ʿAbd al-Muʿṭī Qalʿajī), Taʾrīḵ al-Ṯiqāt (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 1984), p. 296.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ḏahabī (ed. ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar, VII, p. 112.

[36] Ibid., p. 113.

[37] ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Ḥātim, Kitāb al-Jarḥ wa-al-Taʿdīl, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār ʾIḥyāʾ al-Turāṯ al-ʿArabiyy, 1952), p. 184.

[38] Ḏahabī (ed. ʾArnaʾūṭ et al.), Siyar, VII, p. 113.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid., p. 114.

[41] ʿAbd al-Razzāq b. Hammām al-Ṣanʿānī (ed. Ḥabīb al-Raḥmān al-ʾAʿẓamī), al-Muṣannaf, vol. 11 (Beirut, Lebanon: al-Majlis al-ʿIlmiyy, 1970), p. 393, # 20825; Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād al-Marwazī (ed. Samīr ʾAmīn al-Zuhrī), Kitāb al-Fitan, vol. 2 (Cairo, Egypt: Maktabat al-Tawḥīd, 1412 AH), p. 551, # 1549.

[42] ʿAbd Allāh b. ʾabī Šaybah (ed. ʾUsāmah b. ʾIbrāhīm b. Muḥammad), al-Muṣannaf, vol. 13 (Cairo, Egypt: al-Fārūq al-Ḥadīṯah, 2008), p. 328, # 38515.

[43] Al-Ḥasan b. Rašīq al-ʿAskarī (ed. Jāsim b. Muḥammad b. Ḥamūd al-Zāmil al-Fajī), Juzʾ (Kuwait: Dār Ḡirās, 2005), p. 46, # 27.

[44] Ibn ʾabī Šaybah (ed. ʾUsāmah), Muṣannaf, XIII, p. 321, # 38492.

[45] Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād (ed. Zuhrī), Fitan, II, pp. 541-543, # 1526.

[46] Ṭabarānī (ed. Salafī), al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr, II, pp. 54-56, # 1270; ibid., XXIV, pp. 386-388, # 957.

[47] Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥākim al-Naysābūrī, al-Mustadrak ʿalá al-Ṣaḥīḥayn, vol. 8 (Cairo, Egypt: Dār al-Taʾṣīl, 2014), pp. 330-331, # 8836.

[48] ʿAbd al-Razzāq (ed. ʾAʿẓamī), Muṣannaf, XI, pp. 393-394, # 20826; Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād (ed. Zuhrī), Fitan, II, pp. 546-547, # 1531; ibid., p. 552, # 1550.

[49] Fred M. Donner, Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam (Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press, 2010), 129.

Hi!

Very interesting article, much appreciated.

As somebody who views the origins of Islam through the assumptions and worldview of traditionalist Sunni Muslim scholarship, I have not placed much weight on the principle of anachronism as a reason to discount a prophetic origin of a hadith, at least in the absence of any other compelling reason to think it a later fabrication.

Sadeghi’s forthcoming monograph will therefore be an interesting and potentially challenging read, though I doubt it’d do much to convince me personally that traditions such as those referring to the construction of tall buildings are either too vague to pin down or unambiguously refer to events predating the stabilisation of the Hadith corpus. As you can imagine I come from a rather different set of presumptions about the nature and ubiquity of the supernatural than those espoused in the articles ‘Proving History…’ and ‘Theism and Atheism…’

Thank you kindly for this comment. Even though we seemingly disagree on the background probability of miracles and other such supernatural events, I appreciate the engagement.

That said, I wonder if the arguments and considerations I cited still obtain even if you think that miracles, etc., are plausible in principle. Even if you believe that the Quran is from God and Muhammad was a true prophet, the fact that all the unambiguous historical references in Hadith are to the pre-codification era still seems like a novel prediction that confirms the “ex-eventu fabrication” hypothesis, surely?

That said, if you reject the premise that all the unambiguous historical references are to the pre-codification era, I guess the argument would not go through.

Regarding the hadith about “the construction of tall buildings” – does it even refer to “tall buildings”? The versions I checked only state: “you will see barefoot, naked, destitute shepherds arrogantly competing with each other in construction” [تَرَى الْحُفَاةَ الْعُرَاةَ الْعَالَةَ رِعَاءَ الشَّاءِ يَتَطَاوَلُونَ فِي الْبُنْيَانِ]. I know there are slight variations in wording, but I don’t think I’ve seen one that specifies “tall buildings”, unless I’m misunderstanding the text. But I could be missing something.

That said, even if it said tall buildings, I think that the problems I mentioned would still apply.

Either way, thanks for commenting!