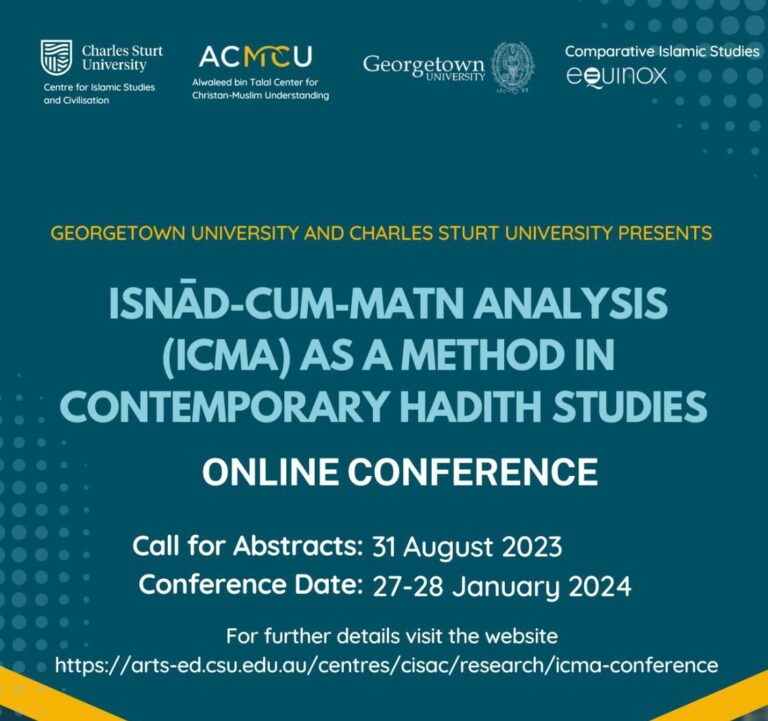

On January the 27th and 28th, 2024, Georgetown University and Charles Sturt University jointly hosted the “Isnād-Cum-Matn Analysis (ICMA) as a Method in Contemporary Hadith Studies” Conference. As both a speaker at the conference and someone with a keen interest in the ICMA and the state of the field, I thought it might be of interest to share my reflections on this intriguing moment in the history of Hadith Studies. What follows is a summary of the nature and context of the conference; some perceptions in the field leading up to the event; my own perceptions and experiences thereof; and some thoughts on its broader impact and implications. In other words, what follows are some personal and socio-historical reflections on the ICMA Conference and Hadith Studies more broadly.

The conference was organised by Jonathan Brown (Georgetown University), Ulrika Mårtensson (the Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Ramon Harvey (Cambridge Muslim College), Sadeq Ansari (Respect Graduate School), and Suleyman Sertkaya (Charles Sturt University) and hosted on Zoom, for the explicit purpose of making it accessible to presenters all around the world. In this respect, the conference was a smashing success, with presenters beaming in from locations as diverse as the United States, England, Norway, the Netherlands, Germany, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Taiwan, Indonesia, and even—God forbid—Australia and New Zealand. We were also joined by viewers from around the world, though the event was not livestreamed: attendance was only possible through a formal application process prior to the conference. The reason for this relative exclusivity was clarified to me by one of the organisers: the conference was about developing the field; having public attendees was just a bonus feature.

The conference was also diverse in the ideological or confessional range of its presenters, including non-Muslim scholars, secular scholars of Muslim background, hybrid secular-traditionalist Muslim scholars, and seminarian Muslim scholars. This too was in line with the stated aims of the organisers, one of whom publicly encouraged “Muslims with a background in traditional Hadith methods AND academic training” to submit proposals alongside their “Western” (i.e., secular and/or non-Muslim) counterparts,[1] and who envisaged the conference as a kind of “meeting of the seas”[2] that would “provide a ‘state of the art’ assessment of isnad-cum-matn analysis from diverse scholarly perspectives.”[3]

Off the record, some colleagues viewed all of this with a certain degree of cynicism. Some wondered whether the conference was an attempt by the organisers—most of whom happen to be Sunnī traditionalists working and publishing in a secular academic context—to frame the ICMA and Hadith Studies more generally as validating the traditional reliability of (Sunnī) Hadith. Another colleague joked to me that we were about to witness the canonisation of Harald Motzki, the figure most associated with the ICMA. The subtext of this joke will be obvious to anyone familiar with the meta-debates surrounding Motzki and the ICMA: time and again, I have seen Motzki’s name invoked—above all by Sunnī traditionalists—as an incantation to ward off skepticism towards Hadith. (Something similar was also observed by Christopher Melchert, who once said of Motzki: “He is a meticulous scholar and not to blame for misuse of his name in support of such propositions as the general reliability of the Six Books, well beyond what he has actually argued for.”[4]) In all of this behind-the-scenes speculation, a common concern was discernible: the potential manufacturing of a false consensus in Hadith Studies for confessional purposes.

Others greeted the announcement of the conference with enthusiasm, either as an opportunity for more discussion on a major Hadith methodology,[5] or even as an opportunity for traditional Islamic methods of Hadith analysis to be rigorously tested against their secular counterparts — iron sharpening iron, so to speak. For example, a friend of mine—a prominent Muslim philosophy nerd on Twitter—posted the following:

It’s hard to overstate how important this is. Whilst secular historians tend to broadly accept the historicity of the Qur’an, they are significantly more sceptical of hadith – despite the fact we only accept hadith which have been historically vetted by our own methods. It’s necessary that Muslims, formally trained in our tradition but also truly versed in the isnad-cum-matn approach (“ICMA”) of secular historians, engage with the latter to defend the former. We’ve been somewhat lacking in this regard so far, for instance sometimes we see ‘ulum al-hadith “defended” by people whose knowledge is lacking to say the least. When you don’t understand the position you’re supposedly defending Islam against, that’s just fideism. In this regard, it is great that the conference and journal aren’t going to be a cloistered apologetics forum where Muslims pat each other on the back and say “look how stupid/evil those others are”. This promises to be a proper intellectual dialogue, where we will begin to uncover where the fault-lines are, and enhance our own understanding of our method through having to think it through against a competitive rival. Of course, I have every confidence that – providing the Muslim interlocutors are competent enough – their position will prove to be the more rationally defensible (even if not on the secular assumptions of the western academy, but on more defensible assumptions).[6]

One of the organisers, cognisant of these various perceptions and narratives, was at pains to publicly clarify that “the aim of the conference is evaluation of ICMA not defence of traditional Hadith methods per se.”[7] Likewise, in the conference’s official booklet, the organisers stressed:

The intention here is to have the most robust possible debate on the proper methods to be used to credibly authenticate or (for those who prefer) date Hadith within the norms of academic scholarship in the broadly Anglophone academic world, and to tackle related questions of comparative global reception, historiographical application and digital manipulation of Hadith data. We hope that this public convening of academic scholars will maintain the highest standards of debate and discussion, even when dealing with what can be tricky and emotive topics. In doing so, we wish to not only move forward our collective knowledge on this important topic but also our collective ability to conduct world-class public-facing academic debate in our globally connected era.[8]

Ultimately, rumours of a Sunnī-traditionalist coup d’état—or, for that matter, a holy Motzki—proved to be unfounded, with the conference proceeding more or less as the organisers intended. Indeed, far from conveying a single party line on Hadith or even the ICMA, the conference instead brought into sharp relief the vast ideological and methodological diversity of global Hadith Studies. On the question of the viability and methodology of the ICMA alone, there was a veritable spectrum of opinion: one scholar rejected the ICMA completely, on the grounds that isnads are fundamentally unreliable; another was critical of certain versions of the ICMA; others sought to combine the ICMA with traditional Islamic Hadith scholarship; and others still advocated the rejection of the former in favour of the latter. Certainly, there was no question of rubberstamping the reliability of Hadith, let alone of Motzki’s elevation to sainthood.

The conference began on a humorous note—after some statements of welcome and acknowledgement by Sertkaya and Ansari—with Brown’s opening remarks, which were delivered to us from the snug fastness of a walk-in closet. We were thus treated not to the traditional backdrop of rows of shelves lined with unread books, but rather, to some kind of minimalist art installation, with racks of empty hangers dangling overhead. Brown—having been exiled from the rest of the house by circumstance—acknowledged his predicament with some wry comments, which set a light and friendly tone for the rest of the conference. This was for the best, in my opinion, since it may have helped to offset the tensions bubbling beneath the surface of our gathering.

Most of us present knew that a fundamental divide existed between the participants. This divide is not, as is sometimes assumed, based upon (Muslim vs. non-Muslim) religious identity per se, but rather, upon methodology or epistemology. On the one hand, there are “Western” and/or secular scholars—including both non-Muslims and Muslims—who are not committed to traditional Islamic Hadith scholarship and do not put much stock in traditional judgements of hadiths and tradents; and on the other hand, there are traditionalist or seminarian Muslim scholars who are deeply committed to traditional (in most cases Sunnī, in some cases Šīʿī) Islamic Hadith scholarship. The divide goes far beyond this, of course, since it also loosely tracks the difference between scholars who believe that miracles and supernatural forces play no discernible role in history and society, on the one hand, and those who believe that they do, on the other. Whatever terms we use to describe this divide, it undoubtedly exists, and most of us present at the conference were cognisant both of its existence and of the side to which we belonged.

This divide was also presumably the subtext of R. Harvey’s introductory statement (immediately following Brown’s opening remarks), in which he sternly reminded all of us present that that was an academic environment; that hostility and rudeness would not be tolerated; and that we should strive to be civil and constructive, regardless of our personal commitments. Taken together, Brown and R. Harvey’s inadvertent good cop / bad cop routine was effective at setting what I thought was a good tone for the conference: much of the feedback that we gave to each other was constructive; strong disagreements were generally expressed politely; and scholars who would have otherwise never interacted with each other came together and exchanged ideas. We attained, in short, a moment of Convivencia, which is no mean feat in a global field characterised by profound methodological and epistemic disagreements.

The conference spanned two days, each comprising three panels. Anyone interested in a comprehensive list of all of the speakers, their affiliations, their bios, and abstracts of their presentations can consult the program booklet (available here). In lieu thereof, what follows is a bare summary of the program:

DAY 1

Panel 1: “Comparative Methods between ICMA and Traditional Hadith” (chaired by Jonathan Brown).

- Belal Abu-Alabbas (University of Nottingham): “Was ICMA how Early Hadith Critics Worked?”.

- Ayše Mutlu Özgür (independent): “Using Isnād-cum-Matn Analysis to Verify the Authenticity of the Transmission Process of Single Strands: A Case Study of G. H. A. Juynboll”.

- Fatma Kızıl (Yalova University): “The Potential for an isnād-cum-matn Analysis Accepted by Muslim and Western Scholars: A Comparative Perspective”.

- Mohammed El-Sayed Bushra (University of Otago): “Home-Grown Organic ICMA? Case Study of an ICMA-Like Approach in Contemporary Muslim Scholarship”.

Panel 2: “Methodological Debates in ICMA I: Assessing Limitations” (chaired by Sadeq Ansari).

- Georg Leube (University of Bayreuth): “Intertextuality during the Process of Transmission or How Isnād-cum-Matn Analysis Misunderstands Textual Criticism”.

- I-Wen Su (National Chengchi University): “The Limits of ICMA: al-hadīth al-gharīb”.

- Ali Aghaei (Paderborn University) & Nahid Hoseinnataj (al-Zahra University): “Reappraisal of Methodological Diversity in Isnād-cum-Matn Analysis (ICMA): A Scrutiny of Sunni and Shia Hadiths on the usage of darb in Quran 4:34 (idribūhunna)”.

Panel 3: “Methodological Debates in ICMA II: Overcoming Limitations?” (chaired by Ramon Harvey).

- Tahir Muhammad (independent) & Salman Nasir (independent): “ICMA and Beyond: Ibn Sīrīn and the Rise of Source Verification as a Means of Hadith Criticism. A Critical Analysis of the Provenance of a Famous Report”.

- Joshua J. Little (University of Groningen): “Beyond the Common Link: The Utility and Necessity of Form Criticism and Literary Analysis”.

- Ulvi Karagedik (University of Karlsruhe): “Text-hadith Review Procedures such as ICMA as a Tool for a Contemporary Islamic Theology? A Critical Review of Some Apostasy Hadiths and the Significance of Isnād-cum-matn Analysis”.

- Mostafa Movahedifar (al-Mahdi Institute): “Bio-Bibliographical Cross-Reference Analysis: A tailoring approach to applying ICMA to Imāmī hadīth”.

DAY 2

Panel 4: “Digital Hadith Methodologies” (chaired by Suleyman Sertkaya).

- Mairaj Syed (University of California, Davis): “Benefits and Limitations of a Computational Approach to ICMA Analysis”.

- Ali Cebeci (Georgetown University): “The Narrator’s Fingerprint: Transmitter-based Stylometry as a Supplement to ICMA Hadith Studies”.

- Mohammad Ghandehari (University of Tehran): “A New Counter-Tashīf Method for Determining the Textual Similarity in ICMA”.

Panel 5: “Global Reception of ICMA” (chaired by Sadeq Ansari).

- Muhamet Ziberi (independent): “Comparative Analysis of the ICMA Method and Classical Islamic Hadith Science: A Focus on Motzki’s Works and the Murder of Ibn Abi al-Huqayq”.

- Rizqa Ahmadi (Universitas Islam Negeri Sayyid Ali Rahmatullah Tulungagung): “The Reception of Harald Motzki’s Isnad cum Matn Theory in The Muslim World: With Special Reference to Indonesian Hadith Scholarship”.

- Bilal Ahmad Qureishi (International Islamic University): “Islamic and Modern Western hadīth Criticism Inter-Receptions: A Qualitative Analysis of ICMA”.

Panel 6: “Historiographical Application of ICMA” (chaired by Ulrika Mårtensson).

- Nicolet Boekhoff-van der Voort (Radboud University): “Surāqa’s Pursuit Continues: Is an Exhaustive Isnād-cum-Matn Analysis indeed necessary?”.

- Seyfeddin Kara (University of Groningen): “Debating the Sanctity of Medina: A Reevaluation of Hadith Narratives”.

- Mehdy Shaddel (Aga Khan University): “Isnād-cum-matn and the Islamic Historical Tradition: The ‘Narrativisation’ Process in the Accounts of Ibn al-Zubayr’s Early Career”.

- S. Beena Butool (Florida State University): “Mapping Isnāds and Mining Biographical Dictionaries: Recovering the Social Legitimation of the Caliph’s Court”.

However, it should be noted that Abu-Alabbas was unable to present on the first day and instead presented at the beginning of the second day; and that Karagedik, Aghaei, and Hoseinnataj were unable to attend at all. This was unfortunate, although there was a silver lining: such absences allowed for more breathing room throughout each day, and more time for questions and discussions.

I was originally intending to summarise those presentations that were of particular interest to me and how I interacted with them, including some of my questions and disagreements. However, as one of the organisers pointed out to me, there is a fair chance—especially given how tiny our field is—that my characterisations and criticisms of any given presentation could influence the eventual peer review thereof when the presentation is submitted as an article. Consequently, I will confine myself to mentioning two general points of interest regarding the conference as a whole, rather than specific comments on specific presentations.

Firstly, even amongst the advocates and supporters of the ICMA, two distinct versions of the method were discernible to me over the course of the conference: (1) a version that systematically appeals to correlations between specific PCLs and CLs and specific underlying redactions of Hadith material to argue for the genuineness of the PCLs and CLs in question; and (2) a version that appeals merely to differences between hadiths in order to establish their independence. This is a major problem given that, in my opinion at least, only the first version is viable, whereas the second is plagued by various conceptual problems: its core premise—that differences in wording and content between two otherwise similar texts preclude direct dependency—seems straightforwardly false; in some articulations, it seems unfalsifiable, with every level of textual variation between texts—high and low—being explained away as a product of independent transmission rather than mutual dependency; and, in some articulations (with formulations such as “sufficiently different” and “so different”), it seems straightforwardly tautologous.[9]

This is not to say that this version of the ICMA is completely without merit: if one hadith contains entire elements or key details that are absent in another, it is reasonable to expect—given the observed tendency for material to accrue and grow in the course of transmission, and given also that additional details were probably generally desired by transmitters and their audiences—that the latter was not directly borrowed from the former.[10] However, this does not preclude a borrowing and subsequent elaboration in the other direction; and it cannot be extended merely to differences in wording between hadiths, since a paraphrastic borrowing—or even a verbatim borrowing corrupted by later scribal errors—could likewise easily produce that level of difference.[11] Consequently, I advocate the first version of the ICMA—referred to above—against the second.[12]

Another recurring question throughout the conference was whether the ICMA and early Sunnī Hadith scholarship should be given equal weight in their conclusions or judgements about hadiths and tradents; or whether the latter should be prioritised over the former; or whether the former should be rejected outright in favour of the latter. This immediately raised an interesting epistemic problem in my mind, which can be rendered as follows. On the one hand, the ICMA is—all else being equal—transparent, involving a clear, step-by-step procedure; checkable sources; coherent and logical reasoning; and reproducible results; all of which confer a strong justification to the conclusions about the transmission—and, in some cases, interpolation and false ascription—of hadiths generated thereby.[13] On the other hand, early Sunnī Hadith criticism is largely opaque, with most judgements of specific hadiths and specific tradents floating free of any specific evidence or argumentation, making any reliance on such judgements little more than an unquantifiable or unaccountable appeal to authority.[14] In light of this epistemic disparity, why should we rely upon ICMA-derived judgements and early Sunnī Hadith judgements equally; let alone prioritise the latter over the former; let alone replace the former with the latter?

Moreover, even if we assume for the sake of argument that there are some general or indirect reasons to accept at least the broad accuracy of these traditional judgements (as indeed was argued by some at the conference), why would such broad judgements override more direct or specific transmissional and historical evidence in any given instance? For example, when an ICMA reveals that a certain hadith evolved organically out of a certain PCL sub-tradition within a broader CL tradition, only for that same hadith to reappear elsewhere with a completely different isnad, why should the overwhelmingly likely explanation therefor—that someone in the isnad borrowed the hadith and falsely attributed it to some alternative set of sources—be superseded by the assertion of a Hadith critic a century or more later—an assertion unaccompanied by any specific or direct argumentation or evidence—that the relevant tradents were all, in some vague or general sense, “reliable” (ṯiqāt)?[15] Or, to move slightly beyond the ICMA to more general historical-critical considerations, when a CL’s hadith closely matches and overtly refers to their specific time and place, why should the overwhelmingly likely explanation therefor—that they fabricated, interpolated, or otherwise anachronistically retrojected the hadith back to earlier authorities—be superseded by the assertion of a Hadith critic a century or more later—again, unaccompanied by any specific or direct argumentation or evidence—that the CL in question was, in some vague or general sense, “reliable” (ṯiqah)?[16]

The most interesting contribution to this ongoing debate—at least in my opinion—was the suggestion that the ICMA actually corroborates early Sunnī Hadith judgements, thereby giving us a reason to generally trust the latter. This would not solve the problem of prioritising early Sunnī Hadith judgements over the ICMA (especially given that, in this scenario, our confidence in the former would be dependent upon the latter), but it would at least give us a reason to put al-Tirmiḏī or al-Dāraquṭnī’s conclusions about the transmission and origin of any given hadith on the same level as those of Motzki et al. However, in my experience, the ICMA does not consistently corroborate early Sunnī Hadith judgements—on the contrary, in numerous cases, I have found that Hadith transmitters later deemed to be “reliable” (ṯiqah) elaborated matns (adding in details and even entire elements), improved isnads (filling in a gap or raising it back to an earlier source), and even—in some cases—borrowed and falsely ascribed material.[17] The results of my form-critical analyses have been even more dire, exposing case after case of unacknowledged borrowings and false isnads even on the part of “reliable” transmitters.[18] In all of this, I am not alone: many other ICMAs have also exposed such problems with major early Hadith transmitters—for example, Gregor Schoeler and Andreas Görke’s systematic ICMAs of the hadiths of ʿUrwah b. al-Zubayr have repeatedly exposed probable elaborations and interpolations on the part of his esteemed student Ibn Šihāb al-Zuhrī, who seems to have been a serial raiser of isnads.[19] In short, the general judgements of early Sunnī Hadith critics are often contradicted by the findings of ICMA (not to mention form criticism and historical-critical analysis), which—for me at least—places them on the same level as the judgements of Joseph Schacht, Gautier Juynboll, or any other pre-ICMA analyst of Hadith: they are secondary sources that merit consultation and may provide valuable insights, but which are generally superseded in any given instance by the ICMA, not to mention form criticism and other historical-critical considerations.[20]

Of course, the viability and utility of early Sunnī Hadith criticism is a long-running debate, and one that I don’t expect to be resolved any time soon.[21] It goes without saying that contemporary proponents of this traditional scholarship would contest some or all of my preceding assertions and characterisations—indeed, several alternative views thereon were expressed throughout the conference.[22] Still, the preceding may at least serve to clarify how secular scholars approach this issue, and thus, to move the discussion forward.[23]

Regardless of such underlying disagreements, I thoroughly enjoyed the first day of the conference: most of the presentations contained points of interest for me; those disagreements that did arise helped me to clarify some of my thinking thereon, even just for myself; the Q&A sessions were positive and constructive; and a spirit of conviviality reigned over the proceedings as a whole.

My own presentation (“Beyond the Common Link: The Utility and Necessity of Form Criticism and Literary Analysis”) occurred at approximately 1:15am Melbourne time, by which point I was succumbing to exhaustion. Out of concern that my delirious state might impede my ability to present and engage with questions, I tried to take a power nap in the 45-minute break preceding my panel, to no avail. I need not have worried, however: when the appointed time finally arrived, I delivered my talk with the usual manic energy, reportedly jolting awake some fellow sleep-deprived attendees in the process.

My presentation essentially combined the ICMA with Albrecht Noth, Patricia Crone, and Ehsan Roohi’s form-critical approach to Hadith: the former (ICMA) was used to reconstruct earlier versions of hadiths, then the latter (form criticism) was used to compare and analyse these reconstructed versions. The specific content and aims of my presentation are most easily summarised by the abstract from the conference program, as follows:

The isnad-cum-matn analysis (ICMA) has allowed recent scholars to reconstruct earlier redactions of some hadiths and to trace these redactions back to early “common links” (CLs), who serve as a terminus ante quem for the material contained therein. Most of these CLs operated at some point during the 8th Century CE, and even the earliest were usually transmitting more than half a century after the Prophet’s lifetime. In order to bridge this gap, some scholars have attempted to reach back behind the CLs, arguing—on various grounds—that at least some CL redactions can be shown to preserve data from earlier sources. Some of this argumentation is questionable, but there is one method that seems especially promising in this regard: form criticism and literary analysis. By subjecting ICMA-reconstructed CL redactions to further form-critical and literary analyses, it is possible to reconstruct and date material preserved by the CLs, even if only approximately. To this end, the present paper provides a number of examples of CL redactions and other transmissions that, when collated and viewed holistically, can be shown to variously preserve earlier, underlying narrative forms and themes. Such results can be positive or negative: on the one hand, we can show that a given form or theme likely predates a given CL, sometimes by a considerable amount of time; but on the other hand, we can show that a given CL redaction is merely one amongst many alternative or conflicting elaborations of a common theme, or one amongst many iterations of a common stock of artificial narrative material. For this reason, the present paper argues that the results of any ICMA should always be subjected to a further form-critical and literary analysis before any historical reconstruction is attempted.[24]

I originally intended to include both a negative and positive example of the way in which this form-critical and literary approach to Hadith can allow us to trace material back beyond CLs. For the negative example, I planned to draw upon a long-running research project of mine regarding the exegetical hadiths on Q. 5:3 (touched upon elsewhere on my blog), arguing that a series of seemingly independent CL redactions actually embody different iterations or remixes of a common stock of narrative material, the development of which can be reconstructed using stemmatics. (This example is ‘negative’ in the sense that it reveals that each of the relevant CL redactions is probably a remix of an elaboration of a basic theme, rather than a genuine historical memory of an actual event.) Meanwhile, for a positive example, I planned to draw upon a recent research project of mine regarding the historical hadiths on ʿUṯmān’s canonisation of the Quran (touched upon in a recent podcast), demonstrating that the relevant reconstructed CL redactions largely embody both narratively and geographically independent reports of the same event, such that they likely embody a common early memory of what actually happened. (This example is ‘positive’ in the sense that it allows us to identify a genuine historical kernel in Hadith.) However, due to time constraints, I only used the example of Q. 5:3 in my presentation, and only a subset of the relevant material at that.

The presentation went smoothly, as did the Q&A: in the latter, I was variously asked (1) how we can distinguish between genuine historical memories and artificial literary constructions;[25] (2) how my conception of artificial narrative development differs from Noth’s;[26] (3) whether instances of abridgement in Hadith transmission pose a problem for my stemmatic process of reconstructing pre-isnad narrative development (which depends on the assumption that material tends to accrue or grow);[27] (4) whether I believe that a genuine historical kernel can still be discerned at the heart of all of the exegetical material on Q. 5:3;[28] and (5) what kinds of Hadith collections my cited material is recorded in.[29] I was generally happy with my responses to these questions, some of which genuinely helped me to clarify even for myself certain distinctions and nuances in my conceptualisation and approach to the relevant Hadith material.

Given the lateness of the hour by the end of my session (approximately 2am Melbourne time) and my consequent exhaustion, I was regretfully forced to retire early, thereby missing the final presentation of the day. In this regard, I must once again extend my apologies to Mostafa Movahedifar, the presenter in question.

My attendance of the second day of the conference was disrupted by a series of unfortunate events. Over the course of the day leading up to conference’s resumption, I travelled across the Australian state of Victoria by bus and train, destined for the rural seaside town of Warrnambool. On a previous train ride from Melbourne to Warrnambool, the carriages had been sparsely populated and included power outlets, so I assumed that, in this case too, a similar situation would obtain. Thus, if it transpired that I was still confined to a train by the time that the conference resumed, I would still be able to access power for my phone and laptop and speak freely during the Q&A.

Fate—and a sinister force known as the V/Line Corporation—had other plans. As I waited at Melbourne’s Southern Cross Station—the gateway to rural Victoria—for the 7pm Warrnambool train at Platform 4 to admit passengers and depart, I learned that the train in question was an old model with no power outlets. No matter, I thought: as long as my laptop and phone last the journey’s duration, I will still be able to attend the conference, ask questions, etc. As the appointed hour of departure approached, however, the smattering of prospective passengers waiting alongside me swelled into a vast throng, dampening any prospect of freely asking questions during the conference (i.e., sans a cacophony of swearing bogans, overexcited children, middle-aged men snarling about politics, and so on). No matter, I thought: most of the passengers will have departed throughout the journey by the time that the conference starts.

The Kafkaesque system of Southern Cross Station soon dashed my optimism: 7pm came and went without any departure; we were then instructed to move over to Platform 5, before being promptly herded back to Platform 4; and, finally, we were informed that there would be no train to Warrnambool that day. There was no way out of the dark city: Warrnambool, it seemed, was Shell Beach.

Thus, as the second day of the conference kicked off with Abu-Alabbas’ presentation on the similarities and differences between the ICMA and early Sunnī Hadith criticism, I found myself crammed into a replacement train to Geelong, with no ability to charge my devices and little prospect of asking questions via audio. I was thus restricted to posting my questions in the Zoom chat, desperately trying to type them out before the Q&A finished and the panel’s chair brusquely moved the proceedings along to the next speaker. In this respect, I owe special thanks to Ansari and R. Harvey, who kindly read aloud some of my questions at various points in the proceedings.

The sun had set by the time I arrived at Geelong Station and a cold wind had begun to blow, which felt appropriate as I continued my descent into the Underworld. My phone’s battery was already close to death when I paid Charon his due and boarded a crowded replacement bus bound for Warrnambool, with little chance of the battery’s surviving the ensuing two-hour drive. In a last-ditch effort to remain connected to the conference, I attempted to charge my phone with my laptop, the latter perched precariously on my knees with the lid closed, lest I inconvenience nearby sleeping passengers. My efforts were in vain: the Zoom app’s energy demand far outpaced my laptop’s meagre supply, and by the time that Panel 5’s first presentation wound to a close, my phone was on 1% battery. I still managed to quickly type out two questions during the Q&A (which R. Harvey kindly read aloud for me), but in the middle of the presenter’s second answer, my phone finally gave out.

I was forced to admit defeat, at least temporarily. I resurrected my phone just long enough to hastily apologise in the Zoom chat for my forced absence, before the battery promptly died again. I spent the remaining hour of my journey brooding upon my misfortune and hoping to rejoin the conference at a later point, but by the time I reached my ultimate destination, I was completely exhausted from a day of public-transport misadventures and had to sleep. In this regard, I must once again extend my apologies to the final panel of the conference, whose presentations I missed. Fortuitously, however, I was later granted access to a recording, which allowed me to listen to these presentations a few days later.

Still, I was fortunate to be able to attend most of the conference, when some friends and colleagues—due to one circumstance or another—were unable to attend at all. The most glaring absence in this regard was Pavel Pavlovitch, who signed up to attend the conference but never received a Zoom link, due to some kind of technical snafu. This was extremely unfortunate: in addition to Pavlovitch’s being one of the leading figures in Hadith Studies at present, some of his research was specifically criticised during the conference, so it would have been beneficial to hear his direct responses thereto. Alas, it was not to be.

Other notable figures from “Western” Hadith Studies were also absent, including: Gregor Schoeler, the co-founder of the modern ICMA; Irene Schneider, an early critic of the ICMA and one of Motzki’s old rivals; Herbert Berg, a long-time critic of the ICMA who recently converted to the cause; Andreas Görke, one of Motzki’s students and perhaps the most notable practitioner of the ICMA today; Ulrike Mitter, another of Motzki’s students and another notable ICMA practitioner (although it should be noted that Mitter appears to have left academia); Jens Scheiner, yet another of Motzki’s students and yet another notable ICMA practitioner; Behnam Sadeghi, the pioneer of a geographical method of Hadith analysis; Stijn Aerts, a relatively new practitioner of the ICMA; Maroussia Bednarkiewicz, another recent ICMA practitioner and my Doktorgeschwister from Oxford; and last but certainly not least, Hiroyuki Yanagihashi, the author of perhaps the single largest published complication of ICMAs thus far undertaken in the field. Absent also was my Oxford Doktorvater Christopher Melchert, another critic of the ICMA who harkens back to a bygone Schachtian era. Melchert is a Merlin-like figure in field, not just because of his iconic beard, but also because of his role as a kingmaker: he alone wields the awesome power to bestow the title of “Dean of Hadith Studies”, which he previously awarded to Motzki, and to Juynboll before him.[30] Alas, neither the conferrer of this title, nor most of the current frontrunners therefor, were present at the conference. This was not for lack of trying: a number of these ʾaʾimmah fī al-ḥadīṯ were contacted by the conference organisers but, for one reason or another, did not—or could not—attend.

Another notable absence was that of Elon Harvey, who was originally scheduled to give the following presentation on the first day of the conference: “Using Biographical Data in Isnād-Cum-Matn Analysis”. Two months before the conference, however, E. Harvey publicly withdrew his presentation in an act of protest against the alleged political stances of Brown, one of the organisers. According to E. Harvey, Brown had ‘valorised’ Hamas and its October 7th attack in several tweets,[31] which is to say: E. Harvey accused Brown of supporting an organisation that has been designated a terrorist group by Israel, the USA, the UK, Australia, the EU, and several other governments. None of the tweets cited by E. Harvey even remotely substantiate his extraordinary charge,[32] however, and it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that it is actually just Brown’s vocal solidarity with the Palestinians in general—in the face of seven decades of Israeli brutality, oppression, and aggression, now reaching plausibly genocidal levels—that disturbs E. Harvey, an avowed supporter of Israel’s “right to defend itself”.[33] (In this context, ‘self-defence’ refers to “one of the most intense civilian punishment campaigns in history” and one “of the most devastating bombing campaigns ever.”[34])

From a purely academic standpoint (i.e., setting moral and political disagreements aside), E. Harvey’s withdrawal from the conference was unfortunate: E. Harvey is already a skilful and insightful researcher and will probably become an important figure in Hadith Studies in the future (assuming, of course, that he chooses to remain in a field that he condemns as “corrupted by identity politics”[35]). In addition to a recent ILS article reconstructing an early imperial Umayyad edict (involving both source criticism and ICMA in particular), E. Harvey has produced numerous Twitter threads and blog articles exploring the textual relationships at play in Hadith, with a keen eye for rabbinical subtexts in particular. Such work remains a valuable resource for the field, and I hope to see his aborted conference presentation reappear someday.

All of this highlights an interesting new aspect of contemporary Islamic Studies (and academia more generally): the open presence of politics in our scholarly relationships and interactions. Of course, politics in academia is nothing new, including the overt kind: whether it was Bernard Lewis (a famous British American Neoconservative) or Maxime Rodinson (a famous French Marxist), some scholars have always worn their politics on their sleeves. Others have expressed their political views only occasionally—but still explicitly—in their writings, as in the case of Patricia Crone’s complaints about “the current politicization of Islamic studies” and an alleged “unholy alliance between conservative Arabists and politicized Islamicists” in her 1992 response article to Robert Serjeant.[36] Even in less direct cases, political inclinations could still be detected, as with Crone’s transparent, seething hostility towards Marxism across her scholarly work.[37] However, all of this pales in comparison to our current era, in which most scholars (at least of middling and junior stature) have active social media accounts on which they openly discuss or otherwise signal their politics. Never before has it been so easy for scholars to discover each other’s opinions on electoral politics, economic policy, secularism, colonialism, gender, sexuality, culture, international relations, and genocide (not to mention each other’s feelings on food, television, cats, cats, and cats). Regardless of how we may view this new ease of access, it remains an unavoidable fact of contemporary academic life, which is to say: the brief spark of political controversy that preceded the ICMA Conference is probably a sign of things to come.

Overall, the conference was a success: it succeeded in bringing together Hadith researchers from all around the world, from both secular and traditionalist backgrounds; it succeeded in facilitating a convivial and constructive environment; and it succeeded in hosting some interesting and stimulating research. It must be said, however, that in one key respect, the conference did not quite achieve one of its stated goals: there was no “robust debate” per se over the best methods of Hadith analysis. This was principally due to time constraints: a presenter would advocate or criticise a method in their presentation and then receive one or two preliminary questions thereon during the Q&A, only for the discussion to be swiftly ended by a panel chair seeking to move us all along to the next presentation. There was thus little prospect of working through our various disagreements, and I would be surprised if any presenter left the conference with serious doubts about their preferred method of Hadith analysis. Still, such disagreements were at least provisionally touched upon throughout the conference, and it is not unreasonable to suppose that a more robust methodological debate in general will result from all of this.

Perhaps the greatest impact of this conference will not be an immediate resolution of all of our methodological and epistemic disagreements, but rather, the forging of academic connections across national, religious, and confessional lines. I myself have certainly benefited in this regard, and I’m sure that others have as well. In this respect, the 2024 ICMA Conference probably represents a historic moment in global Hadith Studies: as far as I am aware,[38] this was the first major meeting of both secular and seminarian Hadith scholars in history. I am glad to have participated, and I look forward to seeing what ultimately comes of it.

* * *

I owe special thanks to Ramon Harvey, for his feedback on and criticisms of a draft version of this article; to Mehrab, CJ Canton, H. M., Marijn van Putten, abcshake, Inquisitive Mind, A.R., and Y., for their generous support over on Patreon; and to N., for his generous support via PayPal.

Anyone else wishing to financially support this blog can do so over on my Patreon (here) or via my PayPal (here).

[1] https://twitter.com/RamonIHarvey/status/1691587272733286808

[2] https://twitter.com/RamonIHarvey/status/1737035739848757493

[3] https://twitter.com/RamonIHarvey/status/1676118786351460355

[4] Christopher Melchert, “The Early History of Islamic Law”, in Herbert Berg (ed.), Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2003), pp. 301-302.

[5] E.g.: https://twitter.com/kizilfatma/status/1676136448372736002

[6] https://twitter.com/Evollaqi/status/1676160108156297218

[7] https://twitter.com/RamonIHarvey/status/1676587149800382466

[8] Isnād-cum-Matn Analysis (ICMA) as a Method in Contemporary Hadith Studies Conference Booklet (January 2024), p. 2. The booklet can be downloaded here.

[9] For more on all of this, see Joshua J. Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age: A Study in the Evolution of Early Islamic Historical Memory”, PhD Dissertation (University of Oxford, 2023) [unabridged version], pp. 116 ff.

[10] This was in fact a premise in my own presentation on form criticism and literary analysis. For some related points and observations, see Michael A. Cook, Muhammad (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1983), pp. 63-64; Patricia Crone, Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam (Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press, 1987), pp. 223-224; Pavel Pavlovitch, The Formation of the Islamic Understanding of Kalāla in the Second Century AH (718–816 CE): Between Scripture and Canon (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2015), pp. 37-39. More generally, see John P. Postgate, “Textual Criticism”, in The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information: Eleventh Edition, vol. 26 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1911), p. 713; Bruce M. Metzger & Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 166 (citing Johann Jakob Griesbach).

[11] Again, see Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age” [unabridged], pp. 116 ff.

[12] For a more detailed discussion thereon, see ibid., pp. 126 ff., 130 ff.

[13] This is not to say of course that there are no problems or defects in the theory and practice of the ICMA; on the contrary, see the source just cited for a discussion thereof. However, this precisely illustrates my point: such problems and defects can be identified and corrected precisely because of the transparency of the ICMA.

[14] For similar or related observations, see Johann W. Fück (trans. Merlin L. Swartz), “The Role of Traditionalism in Islam”, in Merlin L. Swartz (ed.), Studies on Islam (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1981), p. 106; Harald Motzki, “The Origins of Muslim Exegesis. A Debate”, in Harald Motzki, Analysing Muslim Traditions: Studies in Legal, Exegetical and Maghāzī Ḥadīth (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2010), p. 241; Christopher Melchert, Ahmad ibn Hanbal (Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications, 2006), p. 50; Andreas Görke, “Ḥadīth between Traditional Muslim Scholarship and Academic Approaches”, in Majid Daneshgar & Aaron W. Hughes (eds.), Deconstructing Islamic Studies (Boston, USA: Ilex Foundation, 2020), p. 44; etc.

Even in the ʿilal works, in which some evidence is cited for some specific judgements, the evidence is usually sparse, and the actual reasoning process is typically absent altogether. We are thus largely left only with extremely generic principles outlined in a few places, but without the actual process, evidence, argumentation, etc., in any given instance, in the overwhelming majority of cases. For the aforementioned generic principles, see my recent blog article “A Summary of Early Sunni Hadith Criticism” and the references cited therein.

[15] For an example of this sort of thing (Muḥammad b. ʿAmr’s probable borrowing from the CL tradition of Hišām b. ʿUrwah), see Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age” [unabridged], pp. 356 ff. For another example (ʿAbṯar’s probable borrowing from the CL tradition of al-ʾAʿmaš), see ibid., pp. 292-293, 369. For more on this sort of thing, see below.

[16] For a discussion of this sort of thing and a specific example, see my blog article “‘Common Links’ as the Creators of Hadith”.

[17] E.g., Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age” [unabridged], ch. 1 in general, and also chs. 5-6.

[18] In addition to ibid., ch. 3, my research for this very conference yielded various examples, to be discussed in my eventual publication.

[19] See esp. Gregor Schoeler (ed. James E. Montgomery & trans. Uwe Vagelpohl), The Biography of Muḥammad: Nature and Authenticity (New York, USA: Routledge, 2011), pp. 16, 59, 66-67; Andreas Görke, Harald Motzki, & Gregor Schoeler, “First Century Sources for the Life of Muḥammad? A Debate”, Der Islam, Vol. 89, No. 2 (2012), pp. 27-28; Andreas Görke, “Remnants of an old tafsīr tradition? The exegetical accounts of ʿUrwa b. al-Zubayr”, in Majid Daneshgar & Walid A. Saleh (eds.), Islamic Studies Today: Essays in Honor of Andrew Rippin (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2017), pp. 24, 37, 41. For numerous other examples, see the references cited in Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age” [unabridged], pp. 131-132.

[20] This was indeed the approach I took in my PhD dissertation, in which traditional judgements were often taken into account, but always subordinated to more direct textual and historical evidence.

[21] Indeed, the debate over early Sunnī Hadith criticism has existed for as long as early Sunnī Hadith criticism itself, which came into existence in competition with, and defending itself against, at least three rival Islamic approaches to Hadith: that of some rationalists, some Ḵawārij, and others, who outright rejected Hadith; that of other rationalists, who were skeptical of Hadith and demanded extremely widespread transmission, etc.; and that of regionalist jurists, who evaluated Hadith in light of their local legal norms and customs. For more on these early alternative approaches to Hadith, see variously: Joseph F. Schacht, The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1950), esp. part I, chs. 4 and 6; Michael A. Cook, “ʿAnan and Islam: The Origins of Karaite Scripturalism”, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, Vol. 9 (1987), 166-174; Christopher Melchert, “Traditionist-Jurisprudents and the Framing of Islamic Law”, Islamic Law and Society, Vol. 8, No. 3 (2001), 383-406; Eerik Dickinson, The Development of Early Sunnite Ḥadīth Criticism: The Taqdima of Ibn Abī Ḥātim al-Rāzī (240/854-327/938) (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2001), ch. 1; Melchert, Ahmad, pp. 59-66; Jonathan A. C. Brown, Hadith: Muhammad’s Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World, 2nd ed. (Oxford, UK: Oneworld Academic, 2018), ch. 3; Christopher Melchert, “The Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism in the Mid-Ninth Century”, in Petra M. Sijpesteijn & Camilla Adang (eds.), Islam at 250: Studies in Memory of G.H.A. Juynboll (Leiden, the Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2020), pp. 74-102; id., “‘Let me not find one of you reclining on his couch (arīka)’: The Prophet speaks up for his authority”, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta (forthcoming); etc.

For one of the main defences of early Sunnī Hadith criticism against such rival approaches given by the critics themselves, see Dickinson, Development, pp. 9-10, and Christopher Melchert, “The Life and Works of al-Nasāʾī”, Journal of Semitic Studies, Vol. 59, Issue 2 (2014), pp. 398-399, both citing and discussing ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Ḥātim, Kitāb al-Jarḥ wa-al-Taʿdīl, vol. 1 (Beirut, Lebanon: Dār ʾIḥyāʾ al-Turāṯ al-ʿArabiyy, 1953), pp. 349-451.

[22] For another such view, see Ramon I. Harvey, The Qur’an and the Just Society (Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2018), pp. 55-58.

[23] For various other criticisms of traditional Hadith scholarship in modern secular scholarship, in addition to the problem of its opaqueness (discussed above), see: Ignáz Goldziher (ed. Samuel M. Stern and trans. Christa R. Barber & Samuel M. Stern), Muslim Studies, Volume 2 (Albany, USA: State University Press of New York, 1971), esp. pp. 140-144; Schacht, Origins, p. 4; Fück (trans. Swartz), “The Role of Traditionalism in Islam”, p. 106; Gautier H. A. Juynboll, “On the Origins of Arabic Prose: Reflections on Authenticity”, in Gautier H. A. Juynboll (ed.), Studies on the First Century of Islamic Society (Carbondale & Edwardsville, USA: Southern Illinois University Press, 1982), 172; id., Muslim tradition: Studies in chronology, provenance and authorship of early ḥadīth (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983), passim; Melchert, Ahmad, pp. 50-56; id., “The Life and Works of al-Nasāʾī”, pp. 398 ff.; Görke, “Ḥadīth”; Little, “The Hadith of ʿĀʾišah’s Marital Age” [unabridged], esp. chs. 1, 5, and 6; etc.

[24] ICMA Program Booklet, p. 11.

[25] In response to this question, I argued that genuine historical memories can be distinguished from artificial literary constructions by their not being obviously composed of topoi (which can be detected by taking a bird’s-eye view of the corpus as a whole) and their being corroborated by other reports that are textually independent from them (i.e., by reports that do not share the same distinctive elemental sequences and wordings). In hindsight, I would of course add other criteria, such as adherence to established scientific and other background knowledge. The Criterion of Dissimilarity is also useful in this regard.

[26] As the questioner pointed out (and as I will heavily paraphrase from memory here), Noth generally conceived of the material as common templates that were used and reused for different events, whereas I had sketched out a development, a process of continuous and parallel growth in the material. I acknowledged this difference, whilst pointing out that one of the developments I had identified did involve a reskinning of a report (from a story about ʿUmar to a story about Ibn ʿAbbās) that was more along the lines that Noth envisaged. In hindsight, however, I would further add that the main difference between Noth and I—at least in this instance—is that the material conforms to a stemma, which makes it look like it all grew and developed, rather than simply being re-used templates or alternative remixes of a common stock of narrative material. There are certainly other cases where Noth’s conception applies, however, as I will argue in future work.

[27] This question was actually asked twice, in two different ways. In the first instance, I argued that abridgements are the exception (which still allows us to generally reconstruct the development of material along the lines I proposed) and that they can usually be accounted for (e.g., they tend to occur in legal contexts, where the priority was to provide the basic legal element, not the entire narrative). In the second instance, when it was pointed out that abridgement sometimes occurred outside of legal collections (which is certainly true; occasionally, a PCL will abridge a CL’s hadith), I clarified that, even when abridgements occur, the position of the abridged text in the stemma can still be discerned from those elements and wordings that survive the abridgement: whether they are more or less detailed; whether they retain distinctive wordings and elements from some secondary or tertiary stage of development; etc. In other words, growth and development does not only occur in terms of the length of reports, but also, in terms of the details of reports, which means that we can still discern relative position or placement of a hadith on a stemma—even if it is abridged—due to the level of detail in its surviving content. The occurrence of occasional abridgements can thus be overcome within my stemmatic reconstruction.

[28] In response to this, I briefly summarised the problem of speculation as the ostensible source behind the relevant exegetical material, discussed in some detail in my previous blog post.

[29] In response to this, I clarified that the material is recorded not just in exegetical collections, but also in general Hadith collections and others.

[30] Christopher Melchert, “Harald Motzki with Nicolet Boeckhoff-van der Voort and Sean Anthony, Analysing Muslim Traditions: Studies in Legal, Exegetical and Maghāzī Ḥadīth”, Journal of Semitic Studies, Vol. 57, Issue 2 (2012), p. 436: “With the death of G.H.A. Juynboll on 19 December 2010, Harald Motzki has become the undisputed dean of hadith studies.” Of course, Melchert’s appeal to an “undisputed” status gives the impression that the dean is elected by šūrá, but this would not be the first time that an appointment by naṣṣ has been disguised as such…

[31] https://twitter.com/hadithworks/status/1726596571930787962

[32] These amount to: (1) a tweet in which Brown affirmed that he too was witnessing a lot of solidarity with Palestinians in the immediate aftermath of October 7th; (2) a second and third tweet in which Brown expressed skepticism towards Israeli official and media narratives about the details of October 7th; and (3) a fourth tweet in which Brown reiterated this skepticism.

[33] https://twitter.com/hadithworks/status/1726941794208731489

[34] Robert Pape, cited in “Israeli bombardment destroyed over 70% of Gaza homes: Report”, al-Jazeera (31st/December/2023): https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/12/31/israeli-bombardment-destroyed-over-70-of-gaza-homes-media-office

[35] https://twitter.com/hadithworks/status/1727095859437879460

[36] Patricia Crone, “Serjeant and Meccan Trade”, Arabica, Tome 39 (1992), pp. 239-240.

[37] For various examples of Crone’s (sometimes direct, sometimes indirect) criticisms of Marxism in all of its guises, see: Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1977), pp. 125, 138, 183 (n. 1), 205 (n. 26), 227 (n. 56); Pre-Industrial Societies (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1989), passim; “Weber, Islamic Law, and the Rise of Capitalism”, in Toby E. Huff & Wolfgang Schluchter (eds.), Max Weber and Islam (New Brunswick, USA: Transaction Publishers, 1999), p. 259; Medieval Islamic Political Thought (Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), pp. 190, 201-202, 213, 280, 325; “No Compulsion in Religion: Q. 2:256 in mediaeval and modern interpretation”, in Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, Meir M. Bar-Asher, & Simon Hopkins (eds.), Le shīʿisme imāmite quarante ans après: Hommage à Etan Kohlberg (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2009), p. 153; etc.

Crone was the daughter of the chief executive of the Scandinavian Tobacco Company (as reported by the New York Times), making her hostility towards Marxism practically instinctual; but similar considerations presumably apply to other figures in our field as well, without any corresponding anti-Marxist obsession in their writings. The banal assertion that Crone was correct in her criticisms would likewise fail to explain this obsession. I can thus only surmise that Crone was once humiliated as an undergrad by some smug Maoist or Trot, and that she was never able to let it go…

[38] Here I venture into the famously treacherous territory of the argumentum ex silentio, a staple in both secular and traditional Hadith scholarship…