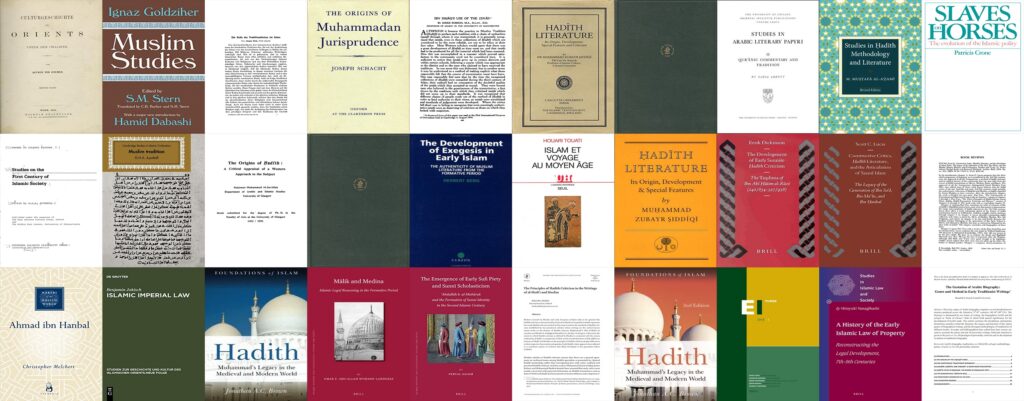

In Part 1 of this series on the origins of proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism (here), I outlined the traditional narratives on this issue, which are plagued by numerous contradictions and cannot be relied upon alone to resolve the historical question of exactly when and where the Hadith-critical method emerged. Now, in Part 2, I survey the secular, critical scholarship from the past century and a half that addresses or touches upon this subject—namely:

- Alfred von Kremer (1875)

- Ignaz Goldziher (1890)

- Johann Fück (1939)

- Joseph Schacht (1950)

- William Watt (1952)

- James Robson (1956)

- James Robson (1965)

- Nabia Abbott (1967)

- Muhammad al-Azami (1977)

- Patricia Crone (1980)

- Gautier Juynboll (1982)

- Gautier Juynboll (1983)

- Sulaiman al-JarAllah (1991)

- Muhammad Siddiqi & Abd al-Hakim Murad (1961/1993)

- Gautier Juynboll (1997)

- Herbert Berg (2000)

- Houari Touati (2000)

- Eerik Dickinson (2001)

- Scott Lucas (2004)

- Christopher Melchert (2006)

- Benjamin Jokisch (2007)

- Jonathan Brown (2009)

- Umar Faruq Abd-Allah Wymann-Landgraf (2013)

- Feryal Salem (2016)

- Belal Abu-Alabbas (2017)

- Pavel Pavlovitch (2019)

- Hiroyuki Yanagihashi (2019)

- Raashid Goyal (2022)

Of course, some of this scholarship is openly religious, in an apologetical or confessional (i.e., Sunnī-traditionalist) sense.[1] However, since this scholarship at least nominally occurs—or attempts to work—within the broad framework of secular, critical scholarship,[2] I have included it here as part of the relevant dialectic regarding the origins of proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism.

Once again, it must be clarified that the focus here is not merely the origins of the transmission or evaluation of Hadith, but rather, the origins of the authentication (taṣḥīḥ) and impugning (taḍʿīf) of hadiths, and the impugning (jarḥ) and accrediting (taʿdīl) of tradents, specifically using the method of those known as “Hadith critics” (al-jahābiḏah and nuqqād al-ḥadīṯ) within the broader proto-Sunnī Hadith movement (ʾaṣḥāb al-ḥadīṯ). In other words, when and where did the basic method shared by the compilers of the canonical Sunnī Hadith collections (“the six books”, al-kutub al-sittah) originate or emerge?

Alfred von Kremer (1875)

One of the earliest statements in the secular academy relating to the history of Hadith criticism can be found in the 1875 first volume of Alfred von Kremer’s monograph Culturgeschichte des Orients unter den Chalifen, in which he stated the following concerning the Madinan traditionist Mālik b. ʾAnas (d. 179/795): “He seems to have been the first who brought the principles of a more rigorous criticism in regards to traditions (die Grundsätze einer strengeren Kritik in Betreff der Traditionen): he rejected every tradition that seemed doubtful to him.”[3] Von Kremer offered no direct sources or evidence therefor, however, and merely mentioned thereafter that Mālik engaged in pious rituals when he transmitted Hadith.[4]

Ignaz Goldziher (1890)

Another early attempt in the secular academy to identify the origins of Hadith criticism can be found in the 1890 second volume of Ignaz Goldziher’s monograph Muhammedanische Studien, with the following remark:

It seems to have been in the time of Ibn ʿAwn (d. 151), Shuʿba (d. 160), ʿAbd Allāh b. Mubārak (d. 181) and others of their contemporaries that criticism of the authorities begins. Criticism was strictest in ʿIrāq and further east where the religious and political parties were most sharply opposed and where they used in the shrewdest way temporal and spiritual means to help their ideas to victory. When in the third century, because of the systematic collection of ḥadīths, the selection of correct and objectionable ḥadīths and the rejection of the suspicious and false ones becomes a need, criticism of the traditions becomes an important part of the science of traditions, whose great flowering is during the third and fourth centuries.[5]

Goldziher relied upon—i.e., accepted at face value—the following in this regard: a list of early isnad critics given by the Khurasanian Hadith critic Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj al-Naysābūrī in his introduction to his al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, which includes the Basran traditionist ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAwn (d. 150-151/767-768); a statement in the Egyptian Hadith scholar ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Bakr al-Suyūṭī’s Ṭabaqāt al-Ḥuffāẓ (ultimately deriving from the earlier Khurasanian Hadith critic Muḥammad b. Ḥibbān al-Bustī), to the effect that the Basran traditionist Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777) was the first tradent critic in Iraq; and some reports from or about the Marwazī traditionist ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Mubārak (d. 181/797) again recorded by Muslim, in which Ibn al-Mubārak comes across as a Hadith critic. Thus, according to Goldziher, Hadith criticism began as early as Ibn ʿAwn, in the early-to-mid 8th Century CE.

In contrast to von Kremer, however, Goldziher does not seem to affirm that Mālik was a proper Hadith critic: “Even to Mālik b. Anas the practical use is the first consideration and he cares little about the rijāl.”[6] In other words, Mālik’s criterion for accepting or rejecting a hadith was its conformity (or lack thereof) to the local custom of his native Madinah, rather than any kind of systematic tradent criticism.

Goldziher also devoted some time to summarising the basic concepts and procedure of Hadith criticism, as in the following:

Each of the informants mentioned in the isnād was investigated in order to gain insight into their character and to find out whether they were unobjectionable morally and religiously and whether they made propaganda for anti-Sunnite purposes, whether their love of the truth was generally established, whether they had personally the ability to repeat correctly what they heard, and whether they were men whose testimony in civil cases would be admitted by a judge without hesitation. Transmission of ḥadīths was considered the highest form of the shahāda, bearing witness, because the rāwī testimony that one has heard this or that saying from this or that person concerns matters of extreme importance for the shaping of religious life. According to the outcome of these investigations, informants were called thiqa (reliable) mutqin (exact), thabt (strong), ḥujja (admitted as evidence), ʿadl (truthful), ḥāfiẓ or ḍābiṭ (who faithfully keeps and passes on what he has heard). These are the qualities of the first order. Transmitters of a lower status are qualified with ṣadūq (saying the truth), maḥalluhu al-ṣidq (his position is that of truth), lā baʾs bihi (unobjectionable). Less than these are those rijāl who are judged with the words ṣāliḥ al-ḥadīth. An even lesser degree of trust will be shown to those whom the critics can give no better marks than that they are no liars (ghayr kadhūb, lam yakdhib). Critics of tradition distinguish these grades and the many intermediate gradations between them with great exactitude, and they circumscribe the theoretical and practical usefulness of traditions according to whether the informants have been awarded one or the other grade of reliability.[7]

However, according to Goldziher, the actual determining of a tradent’s reliability and a hadith’s soundness involved a large amount of subjectivity on the part of the Hadith critics:

The critics themselves maintain that the ability to judge the value of traditions can only be gained by long-continued handling of this material (bi-ṭūl al-mujālasa wa’l-munāẓara wa’l-mudhākara). In the absence of strict methodical rules, the subjective faculty of a man, his sense of discrimination, was in the end taken as decisive: dhawq al-muḥaddithīn, as it is called, the scholar’s subjective taste in differentiating the ‘healthy’ from the ‘diseased’.[8]

In other words, in the final analysis, Hadith criticism boiled down to a subjective appraisal or even mere intuition, rather than any kind of objective set of factors or formal criteria.

Johann Fück (1939)

Goldziher’s chronology of the rise of Hadith criticism was seemingly rejected half a century later by Johann Fück in his 1939 article ‘Die Rolle des Traditionalismus im Islam’, though without explicitly mentioning his predecessor:

The traditionists themselves were clear about the fact that the sunna constituted no closed system of regulations and doctrinal propositions, but that the ideal or norm had to be painstakingly extrapolated from often incomplete and contradictory traditions. This task required a careful examination of numerous reports and a cautious weighing of all circumstances which might affect their reliability. From this fact arose, at the beginning of the Abbasid period, the earliest attempts at a critical evaluation of traditions. It was necessary, given the nature of oral tradition, that this critical study should begin with an examination of the trustworthiness of the individual authorities. The question of their manner of life, therefore, played no small role in this investigation. How could the critic recognize an individual as a reliable witness who in his personal conduct violated the sunna? Since they lacked generally recognized criteria, they did not always escape the danger of premature judgments resulting from personal bias. Thus Shuʿba (83-160 A.H.), who was regarded as the founder of the critical analysis of authorities, contested transmitters because he disliked the way they prayed. Similar statements were reported from another critic of this period, Wuhaib (108-165 A.H.).[9]

Fück referred in passing to a report from the Baghdadian Hadith critic Jazarah Ṣāliḥ b. Muḥammad (recorded by the Egyptian Hadith scholar Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī), to the effect that the Basran traditionist Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777) was the first tradent critic. However, Fück highlighted the unsystematic nature of the evaluations of hadiths and tradents—on the part of both Šuʿbah and the subsequent Basran traditionist Wuhayb b. Ḵālid (d. 165/781-782)—in the mid-to-late 8th Century CE, in contrast to what would come later. In this respect, Fück may have discerned the difference between Hadith criticism proper and earlier, cruder forms of criticism, thereby foreshadowing the work of Eerik Dickinson.

Joseph Schacht (1950)

In his influential 1950 monograph The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence, Joseph Schacht focused on the development of early Islamic jurisprudence and the emergence and use of Hadith in that context, but did touch upon the history of Hadith criticism in passing:

The use of traditions in the ancient schools of law took little account of the standards of criticism which in the time of Shāfiʿī had been developed by the specialists on traditions (Tr. III, 62). Their technical terms thābit ‘well-authenticated’, mashhūr ‘well-known’, mauṣūl or muttaṣil ‘with an uninterrupted isnād’, maqṭūʿ or munqaṭiʿ ‘with an interrupted isnād’, mursal ‘lacking [the mention of] the first transmitter’, ḍaʿīf ‘weak’, majhūl ‘unknown, not identified’, munkar ‘objectionable’, were known to Shāfiʿī and his opponents, the adherents of the ancient schools, alike, but it was left to Shāfiʿī to introduce as much of the specialized criticism of traditions as existed in his time into legal science.[10]

In other words, whereas the jurists of the regional legal traditions of centres like Kufah and Madinah assessed Hadiths on the basis of their conformity to local custom, consensus, and other such considerations, the Hijazo-Egyptian jurist Muḥammad b. ʾIdrīs al-Šāfiʿī (d. 204/820)—as member of the proto-Sunnī People of Hadith but not himself a Hadith critic—appealed to the expertise of the Hadith critics in this regard.

Thus, according to Schacht, Hadith criticism had already emerged by the time of al-Šāfiʿī (i.e., by the beginning of the 9th Century CE), such that he could cite its practitioners and results in his argumentation.

William Watt (1952)

In his 1952 article ‘The Condemnation of the Jews of Banū Qurayẓah’, William Watt briefly touched upon the origins of tradent criticism, in the following:

It may further be noticed that the study of the biographies of the transmitters commenced about 150; Shuʿbah (d. 160) was one of the first noted for this study (Ibn Ḥajar, Tahdhīb, IV, no. 580; cf., Goldziher, M.S., II, index).[11]

In other words, according to Watt (citing both the preceding work of Goldziher and the report from Jazarah recorded by Ibn Ḥajar), systematic tradent criticism arose in the middle of the 8th Century CE with the likes of Šuʿbah. In contrast to Fück, however, Watt does not seem to identify Šuʿbah as the sole founder of this discipline, but rather, some kind of co-founder.

James Robson (1956)

In his 1956 article ‘Ibn Isḥāq’s use of the Isnād’, James Robson broadly touched upon the rise of Hadith criticism, in the following:

It is sufficient to notice that isnāds grew up in certain districts and within certain schools, following a course which was appropriate to the district and to the men who claimed to have received the traditions. In one sense this was dishonest, but in another sense it may be understood as a method of making explicit what those responsible felt that the course of transmission must have been. One may reasonably feel sure that by the time the recognized collections of Ḥadīth were compiled during the third century of Islām, their authors had no conception of the doubtful quality of the isnāds which they accepted as sound. They were honest men who believed in the genuineness of the transmission, a fact shown by the readiness with which they criticized isnāds which did not come up to their standards. It was recognized that different classes of people made use of the method of Ḥadīth in order to lend authority to their views, so isnāds were scrutinized and standards of judgments were developed. Where the critics fell short was in failing to recognize that even seemingly authoritative isnāds were as deserving of criticism as those on which they looked with suspicion.[12]

Robson here contributed a valuable insight regarding a historic shift in the early Muslim understanding of Hadith that must have taken place across the 8th and 9th Centuries CE: whereas earlier Muslims created or inferred isnads on the basis of the (ideal or actual) scholarly genealogy of their given (regional or sectarian) community and thus must have viewed isnads as in some way non-literal (e.g., as symbolic, or guesswork, or the product of inference), the later Hadith critics evidently possessed a historicist or literalist outlook on isnads (i.e., as accurately-passed-on historical records). For example, the assigning of errors in transmission to specific tradents only really makes internal sense if Hadith and isnads are assumed to be literal, historical records of transmission—thus, the rise of the Hadith critics either required or precipitated a rise in a literalist attitude towards the historicity of Hadith and isnads. However, in the article under consideration, Robson never pinpointed exactly when the Hadith critics first arose, merely noting that they were active by the mid-to-late 9th Century CE, when the canonical Sunnī Hadith collections were created.

James Robson (1965)

In contrast to his earlier contribution, Robson explored the rise of Hadith criticism in a bit more detail in his 1965 encyclopaedia entry ‘al-Djarḥ wa ’l-Taʿdīl’, in which he outlined the following general chronology:

In the course of the 2nd/8th century when it was realized that many false traditions were being invented, interest in the transmitters developed, and statements regarding their qualities were made. In the 3rd/9th century books began to be written, generally in the form of lists of men with their dates, and statements regarding their credibility. We also find notes on the qualities of traditionists in the canonical Sunan collections of tradition, in the Sunan of al-Dārimī, and elsewhere. In the introduction to his Ṣaḥiḥ Muslim found it necessary to justify the investigation of traditionists’ credentials because many felt it was wrong to criticize them. Such views must have continued for a long time, for al-Ḥākim (d. 405/1014) still found it necessary to defend the practice. When books on ʿIlm al-ḥadīth were written (4th/10th century onwards), al-djarḥ wa ’l-taʿdīl formed a recognized branch of the subject.[13]

Once again, however, Robson did not go into much detail on the matter: he identified the 8th Century CE in general as the era when tradent criticism began, and the 9th Century CE as the era when a proper tradent-critical literature arose.

Nabia Abbott (1967)

A somewhat sanguine chronology of the history of Hadith criticism was posited by Nabia Abbott in her 1967 second volume of her monograph Studies in Arabic Literary Papyri, in which she identified the roots of Hadith criticism with the Companions and Followers, whilst still conceding a later systematisation:

The controversy over the authenticity of Islāmic Tradition is intimately associated with the rapid growth of ḥadīth during the first two centuries of Islām, when as a result of the initial caution exercised by the Companions and older Successors relative to the isnād biographical science (ʿilm al-rijāl) was formalized by such scholars as Ibn Juraij, Shuʿbah ibn al-Ḥajjāj, and Wuhaib ibn Khālid al-Baṣrī and further refined under such critics as ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Mahdī and Yaḥyā ibn Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān to become a sharp tool, the jarḥ wa al-taʿdīl, in the hands of such master ḥadīth critics as Yaḥyā ibn Maʿīn and ʿAlī ibn al-Madīnī. Major ḥadīth collectors who were active around the end of the second century, of the caliber of Ibn Ḥanbal, Bukhārī, and Muslim, used fully this indispensable tool of all traditionists who were more than passive channels of transmission.[14]

In other words, it was only with mid-8th-Century traditionists like the Basran Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777) that Hadith criticism proper emerged, although it still underwent some kind of refinement thereafter at the hands of his Basran students Yaḥyá b. Saʿīdal-Qaṭṭān (d. 198/813) and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdī (d. 198/814).

Elsewhere, however, Abbott seems to contradict this chronology by placing the rise of Hadith criticism much earlier than Šuʿbah et al., in the era of the Followers and even the junior Companions: “Ḥadīth critics began to appear to appear around the end of the first century, when several trends reflected the need for a cautious approach to the materials in circulation.”[15] Perhaps Abbott regarded these first as proto-critics, in contrast to the systematic critics of the generation of Šuʿbah et al.

Finally, it is of interest that, according to Abbott, the actual method of the proto-Sunnī Hadith critics is largely unknown, but at the same time, was highly subjective:

What, then, were the factors, expressed or tacit, that were involved in the final stage of the series of tests that determined the selection to traditions and therefore a high probability of survival? The answer to this important question is nowhere pinpointed in the numerous sources at my command and, to the best of my knowledge, has been overlooked by modern scholars. This is not surprising when one considers the high degree of subjectivity that was involved in all attempts at the evaluation and selection of ḥadīth. The early Muslims realized that in the final analysis all such judgements, despite the necessary groundwork to discover the biographical and in many instances the historical data, depended on the ability acquired through long experience.[16]

In other words, Abbott—thereafter citing various reports to this effect—argued that we know little of the Hadith-critical method, and that what little we do know seems to involve a good deal of subjectivity and even intuition on the part of the critics. In this respect, Abbott seems to have agreed with Goldziher.

Muhammad al-Azami (1977)

Another highly sanguine model of the emergence of Hadith criticism was outlined by Muhammad Mustafa al-Azami in his 1977 monograph Studies in Ḥadīth Methodology and Literature, in which he likewise identified its origins amongst the Companions: “We find certain Companions checking other Companions, asking them to be very sure and precise as to what they related, on the authority of the Prophet.”[17] Similarly, after citing reports of various Companions’ “investigation or verifying” of claims about the Prophet, Azami reiterated: “In light of these events, it can be claimed that the investigation of Ḥadīth or, in other words, criticism of Ḥadīth began in a rudimentary form during the life of the Prophet.”[18] Such “criticism of ḥadīth” continued after the death of the Prophet, with the likes of ʾAbū Bakr (d. 22/634), ʿUmar (d. 23-24/644), ʿAlī (d. 40/661), ʿĀʾišah (d. 57-58/677-678), and ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar (d. 73-74/692-694).[19]

According to Azami (citing a schema outlined by Ibn Ḥibbān), “the criticism of ḥadīth” continued with the major Followers of Madinah, who passed “this science” in turn to the Followers of the Followers in Madinah, especially Ibn Šihāb al-Zuhrī (d. 124/741-742), Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd al-ʾAnṣārī (d. 143/160), and Hišām b. ʿUrwah (d. 146-147/763-765).[20] Meanwhile, there were also “ḥadīth critics” amongst the Followers of other regions, such as the Kufan Followers Saʿīd b. Jubayr (d. 95/714) and ʿĀmir b. Šarāḥīl al-Šaʿbī (d. 103-106/721-725 or 110/728-729), the Yemeno-Meccan Ṭāwūs b. Kaysān (d. 105-106/723-725), and the Basran Followers Ḥasan (d. 110/728) and Muḥammad b. Sīrīn (d. 110/729), who were succeeded in turn by the Basran traditionists ʾAyyūb al-Saḵtiyānī (d. 131-132/748-750) and ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAwn (d. 150-151/767-768).[21]

Azami continued: “After his period, the criticism of ḥadīth entered a new phase.”[22] According to Azami, the 8th Century CE saw the rise of regular travelling in search of Hadith, producing a new generation of Hadith critics who evaluated and scrutinised the hadiths and tradents of every region—in particular:

- Sufyān al-Ṯawrī; Kufan; d. 161-162/777-779.

- Mālik; Madinan; d. 179/795.

- Šuʿbah; Basran; d. 160/777.

- al-ʾAwzāʿī; Syrian; d. 151-157/768-774.

- Ḥammād b. Salamah; Basran; d. 167/784.

- al-Layṯ b. Saʿd; Egyptian; d. 175/791.

- Ḥammād b. Zayd; Basran; d. 179/795.

- Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah; Kufo-Meccan; d. 198/814.

- Ibn al-Mubārak; Marwazī; d. 181/797.

- Yaḥyá al-Qaṭṭān; Basran; d. 198/813.

- Wakīʿ; Kufan; d. 196-197/812.

- Ibn Mahdī; Basran; d. 198/814.

- al-Šāfiʿī; Hijazo-Egyptian; d. 204/820.

Of these, “the most famous” were Šuʿbah and his two leading students, Yaḥyá al-Qaṭṭān and Ibn Mahdī.[23] These scholars “in turn produced numerous famous scholars in the field of criticism,”[24] including Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn (d. 233/848) and ʾAḥmad b. Ḥanbal (d. 241/855) in Baghdad, in turn produced famous students such as Muḥammad b. ʾIsmāʿīl al-Buḵārī (d. 256/870) in Transoxania, Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj al-Naysābūrī (d. 261/875) in Khurasan, and many others.

Finally, Azami went into some detail regarding the actual Hadith-critical method, arguing that it primarily involved the comparison of transmissions and texts: “By gathering all the related materials or, say, all the aḥadīth concerned, comparing them carefully with each other, one judges the accuracy of the scholars.”[25] In addition to citing statements to that effect from ʾAyyūb al-Saḵtiyānī (concerning consulting different teachers), Ibn al-Mubārak (concerning the comparison of hadiths), and Ibn Maʿīn (concerning his investigation of a certain traditionist),[26] Azami related this basic principle back various episodes featuring ʾAbū Bakr, ʿUmar, and others’ demanding independent witnesses for Prophetical precedents, thereby reiterating the notion that Hadith criticism had its roots with the Companions.[27]

Patricia Crone (1980)

In her 1980 monograph Slaves on Horses, Patricia Crone briefly commented upon the history of Hadith criticism in passing, in the following:

Lists of muḥaddithūn, on the other hand, attesting to the rabbinicization of Islam, are of later origin (pace ibid., p. 92) and first appear in Iraq: we are told that Shuʿba, who died in Basra in 160, was the first to occupy himself with the study of traditionists (Ibn Ḥajar, Tahdhīb al-tahdhīb, Hyderabad 1325–7, vol. iv, p. 345)…[28]

In other words, Crone appears to have held the same view as Fück (albeit extremely noncommittally), and on the basis of the very same evidence (the report from Jazarah recorded by Ibn Ḥajar): the Basran traditionist Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777) was the first to study traditionists (i.e., the founder of tradent criticism).

Gautier Juynboll (1982)

In his 1982 article ‘On the Origins of Arabic Prose’, Gautier Juynboll briefly addressed the history of Hadith criticism—or at least tradent criticism—in passing, in the following:

The study of transmitters, the so-called ʿilm al-rijāl, came into being relatively late. Shuʿba b. al-Ḥajjāj (died 160) was reputedly the first traditionist who scrutinized transmitters in Iraq, and who rejected the weak. “If it had not been for Shuʿba,” it says in his tarjama, a saying ascribed to Shāfiʿī, “the ḥadīth would not have been known in Iraq.” A spurious saying perhaps, but nevertheless a very relevant one.[29]

In other words, Juynboll held to the same view as Fück and Crone, and on the basis of the very same evidence (the report from Jazarah recorded by Ibn Ḥajar): the Basran traditionist Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777) was the founder of tradent criticism.

Gautier Juynboll (1983)

Juynboll elaborated upon his chronology of Hadith criticism and Hadith more broadly in his 1983 monograph Muslim tradition, in which he argued that isnads in general only arose beginning in the 680s and 690s CE; that the widespread and systematic use of isnads only commenced a generation or two later, in the early-to-mid 8th Century CE; and that the systematic evaluation and criticism of isnads arose later still, in the mid-to-late 8th Century. Juynboll thus seemingly dismissed reports of (at least senior) Companions’ engaging in Hadith criticism as anachronistic:

Already during the life of the prophet, or shortly after his death, certain Companions are said to have shown caution by not immediately accepting everything that was related before having scrutinized the informant. ʿUmar and ʿAlī are said to have been the first who screened their informants. But according to Muslim scholarship the isnād came definitely into use after the troubles ensuing from the murder of the caliph ʿUthmān in 35/656…[30]

According to Juynboll, the first instance of isnad criticism occurred with the Kufan Follower ʿĀmir b. Šarāḥīl al-Šaʿbī (d. 103-106/721-725 or 110/728-729) at the start of the second fitnah (during the late 1st Century AH), per a report recorded by the Persian Hadith critic al-Ḥasan b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Rāmahurmuzī:

The first systematic examination of informants ever recorded is reported to have occurred in Kūfa when Shaʿbī (d. 103-10/721-8) interrogated ar-Rabīʿ b. Khuthaym as to his informant regarding a certain ḥadīth. Ar-Rabīʿ is said to have died after the battle of Karbalāʾ of 61/680, so the conversation, if it is assumed to be historical, must have taken place prior to that date. In view of Shaʿbī’s alleged date of birth, given as 20—which makes him either eighty-three or ninety when he died—or 31, which makes him seventy-two or seventy-nine at the time of his death, and in view of the fact that so many traditionists pretended to be older than they were in reality—common practice of especially Kūfan transmitters (see pp. 46ff. below)—I think that it is safe to say that it took place in the same year or only a short time earlier.[31]

In other words, the first instance of isnad criticism occurred concurrently with the first appearance of isnads (in the 680s CE), according to Juynboll’s chronology. This episode was seemingly ad hoc or a one-off, however—according to Juynboll, systematic isnad criticism only arose subsequently, with the Basran traditionist Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777):

If it is assumed, then, that this first examination of transmitters occurred sometime in the early sixties, the first isnād critic as such, who systematically examined every isnād and made the reliability of transmitters a conditio sine qua non for accepting their traditions, was Shuʿba b. al-Ḥajjāj, who died in 160/777 when he was allegedly 77 years old. He is recorded to have said to someone: Innaka lā takādu tajidu aḥadan fattasha ’l-ḥadīth taftīshī wa-lā ṭalabahu ṭalabī wa-qad naẓartu fīhi fa-wajadtuhu lā yaṣiḥḥu minhu ath-thulth (i.e. You will hardly find anyone who scrutinized the tradition or searched for it as I have done and after inspection I found not [even] one third of it to be ‘sound’. Since Shuʿba allegedly occupied himself with collecting traditions for the last thirty years or so of his life, we can assume the starting date of systematic rijāl criticism in Islam to be at about 130/747. And for Medina we have the report concerning Mālik b. Anas (d. 179/795), although this, admittedly, does not imply that he was necessarily the first isnād critic as such. There is, however, no explicit mention in the sources of any rijāl expert from Medina who preceded Mālik, and in view of the still far from sophisticated use of isnāds in the Muwaṭṭaʾ that is hardly surprising.[32]

Juynboll argued for Šuʿbah as the founder of tradent criticism or isnad criticism primarily on the basis of some reports recorded in the Arabo-Islamic prosopographical genre of innovators, pioneers, or “firsts” (ʾawāʾil)—in particular: (1) a statement recorded by Ibn Ḥajar (ultimately deriving from Ibn Ḥibbān), to the effect that Šuʿbah was the first tradent critic in Iraq; (2) another statement recorded by Ibn Ḥajar (ultimately deriving from Jazarah), to the effect that Šuʿbah was the first tradent critic in toto; and (3) a statement from Šuʿbah himself recorded by the Balḵī rationalist ʾAbū al-Qāsim al-Kaʿbī, to the effect that Šuʿbah was the pioneer of a new critical approach to Hadith. For 747 CE as the approximate date of the commencement of Šuʿbah’s activities, Juynboll appealed to a biographical report recorded by al-Rāmahurmuzī. Finally, for Mālik as the first Hadith critic of Madinah, Juynboll appealed to both (1) a report to this effect recorded by Ibn Ḥibbān and (2) the absence of any clear references to prior Madinan Hadith critics.

However, it should be noted that Juynboll distinguished between tradent or isnad criticism and matn criticism: al-Šaʿbī represented the first instance of isnad criticism in particular, and Šuʿbah represented its first systematic practitioner. By contrast, some form of matn criticism plausibly preceded both:

It is not likely that hadith criticism in Islam began with isnād criticism, as, indeed, ḥadīth may have had its origins in a time when the institution of the isnād had not yet come into existence. Rather, it seems safe to assume that it was the isnād, eventually to become an indissoluble part of a tradition, through which an attempt was made to authenticate further, and perhaps successfully, the text of the tradition. But prior to the institution of the isnād there must have been a time during which certain ḥadīths, brought into circulation in one way or another, made certain people raise their eyebrows. This probably resulted in a critical sense with various people based mainly upon intuition, an intuition which never seems to have disappeared entirely, if we take into account how Abū Ḥātim (d. 277/890) tackled ḥadīth.[33]

In other words, according to Juynboll, isnad criticism—the main staple of Hadith criticism proper—was likely preceded by some kind of early, informal, intuition-based matn criticism, before the rise of isnads, when Hadith consisted of little more than free-floating claims, rumours, stories, gossip, and anecdotes. Moreover, according to Juynboll (here in agreement with Goldziher and Abbott), an element of intuition lingered on even amongst the proper Hadith critics of the 9th Century CE.

Sulaiman al-JarAllah (1991)

Almost a decade after Juynboll, a refutation of his hypothesis was attempted by Sulaiman Muhammad al-JarAllah in his 1991 PhD thesis ‘The Origins of Ḥadīth’, defending a traditional Sunnī perspective on the history of Hadith criticism.

To begin with, JarAllah asserted: “In dealing with the awāʾil pertaining to the examination and criticism of isnād, Juynboll disregards various reports.”[34] In particular, JarAllah pointed to certain statements and reports in the works of Ibn Ḥibbān, al-Ḥākim, and al-Ḏahabī, to the effect that some form of Hadith criticism had already commenced amongst the Companions (such as ʾAbū Bakr, ʿUmar, and ʿAlī).[35] Thereafter, JarAllah concluded:

At any rate, interrogation of transmitters is recorded in various reports in which early Companions applied it to their informants, as the awāʾil reports, mentioned above, point out and attribute the initiation of this practice to them. The Successors followed them in this and we find Successors not only questioned other Successors about their material, as al-Shaʿbī did, but also Companions.[36]

JarAllah further argued that Juynboll had misinterpreted the report from al-Rāmahurmuzī about Šuʿbah, which “is not about collecting ḥadīths but propagating them”, and which—together with other reports—actually implies or entails that “Shuʿbah started collecting hadith in his early life.”[37] Thereafter, JarAllah appealed to other ʾawāʾil reports about the first Hadith critics—beyond those relied upon by Juynboll—to reiterate that Hadith criticism commenced earlier than Šuʿbah:

However, other awāʾil reports give other earlier people, and, indeed, one puts Shuʿbah in third place. These also are known to Juynboll. One of them describes Ibn Sīrīn (d. 110) as “the first to criticise the transmitters and to distinguish between the reliable ones and the others.” In another report, Ibn al-Madīnī (d. 234) is recorded to have said: “we do not know of anyone prior to Muḥammad b. Sīrīn that scrutinized the ḥadīth and examined the isnād. Then there were Ayyūb and Ibn ʿAwn; then there was Shuʿbah, then Yaḥyā b. Saʿīd and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān [b. Mahdī].”

In conclusion, from the foregoing it becomes clear that the awāʾil reports adduced by Juynboll do not affect the question of the early existence of ḥadīth. Indeed, if we take the awāʾil evidence at face value, it appears rather to indicate that ḥadīth had early origins.[38]

In short, on the basis of certain ʾawāʾil and other reports, JarAllah concluded that Hadith criticism commenced with the Companions and continued with the Followers, against Juynboll’s view.

Muhammad Siddiqi & Abd al-Hakim Murad (1961/1993)

Another sanguine chronology of the history of Hadith criticism was posited by Muhammad Siddiqi and Abd al-Hakim Murad in the latter’s 1993 redaction of the former’s 1961 monograph Ḥadīth Literature, in which he argued that Hadith criticism can be traced all the way back to the Companions.

To begin with, Siddiqi and Murad argue that the Companions must have been motivated by their pious commitments and sensibilities to be rigorous in their transmissions from the Prophet and in their evaluation of claims and anecdotes about him—thus, the existence of various reports depicting ʾAbū Bakr (d. 22/634) and ʿUmar (d. 23-24/644)’s demanding independent witnesses to confirm claims about the Prophet, ʿAlī (d. 40/661)’s demanding oaths from those making claims about the Prophet, and so on.[39]

This scrupulousness was inherited by some of the Followers and the Followers of the Followers, “a core of honest and committed scholars” who “dedicated their lives to authentic scholarship, carefully ascertaining what was authentic, preserving its purity and genuineness, and propagating it among the community at large.”[40] For example, the Kufan Follower ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Laylá (d. 82-83/701-702) reportedly expected Hadith experts to reject some hadiths; the Basran Follower Muḥammad b. Sīrīn (d. 110/729) reportedly cautioned students not to transmit from sectaries or heretics; and the Yemeno-Meccan Follower Ṭāwūs b. Kaysān (d. 105-106/723-725) and the Basran Follower ʾAbū al-ʿĀliyah Rufayʿ b. Mihrān (d. 90-93/709-712 or 106/724-725) both reportedly cautioned students to only transmit from pious sources.[41]

The Followers’ “spirit of scrupulous care with regard to choice of teachers” was then inherited by the Followers of the Followers and traditionists of the 8th Century CE—for example: the Madinan traditionist ʾAbū al-Zinād ʿAbd Allāh b. Ḏakwān (d. 130/748) reportedly discriminated even amongst reliable tradents; the Basran traditionist ʾIsmāʿīl b. ʾIbrāhīm b. ʿUlayyah (d. 193-194/808-809) reportedly cautioned students to only transmit from pious sources; and the Madinan traditionist Mālik b. ʾAnas (d. 179/795) was reportedly highly selective in his sources and did not transmit from certain types of tradents.[42] Moreover: “Many of Mālik’s contemporaries shared his punctilious care over the authorities from whom they received their material”, including the Basran traditionist Šuʿbah b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777), the Kufan traditionist Sufyān al-Ṯawrī (d. 161-162/777-779), the Basran traditionists Ḥammād b. Salamah (d. 167/784) and Ḥammād b. Zayd (d. 179/795), the Marwazī traditionist ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Mubārak (d. 181/797), the Khurasanian traditionist al-Fuḍayl b. ʿIyāḍ (d. 187/802-803), and the Basran traditionist Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān (d. 198/813).[43]

According to Siddiqi and Murad: “This careful scrutiny of those who related traditions was continued with unabated vigour by a large number of the students of ḥadīth in the subsequent generations.”[44] Thus, Hadith criticism passed to the major traditionists of the early 9th Century CE, especially Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn (d. 233/848) and ʾAḥmad b. Ḥanbal (d. 241/855) in Baghdad; and hence to the canonical Hadith collectors of the mid-to-late 9th Century CE, such as Muḥammad b. ʾIsmāʿīl al-Buḵārī (d. 256/870) and Muḥammad b. ʿĪsá al-Tirmiḏī (d. 279/892) in Transoxania; and hence to many others.[45]

This same general schema is repeated for tradent criticism in particular: Siddiqi and Murad argue that this discipline had its roots even amongst the Companions, as in an instance when ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar (d. 73-74/692-694) reportedly questioned ʾAbū Hurayrah (d. 57-59/676-679)’s personal bias regarding a hadith that he transmitted; that it continued amongst the Followers, as when ʾIbrāhīm al-Naḵaʿī (d. 96/714) rejected certain tradents as liars; that it further continued with the Followers of the Followers, as when Qatādah b. Diʿāmah (d. 117-118/735-736) and ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAwn (d. 150-151/767-768) criticised or impugned their contemporaries; and that it further continued with the great traditionists of the mid-to-late 8th Century CE, such as Šuʿbah, the two Sufyāns, and Mālik, who “all instructed people to make the true nature of unreliable narrators known to the public.”[46] Siddiqi and Murad thus explained away certain reports that seem to identify a later starting point for tradent criticism: “As a matter of fact, numerous Companions and Successors had criticised various reports of traditions; and Shuʿba and Yaḥyā ibn Saʿīd, who are generally said to have been the first critics of the reporters, had only made special efforts with regard to their criticism.”[47] To corroborate this interpretation, Siddiqi and Murad cited the Jurjānī Hadith critic ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAdī al-Qaṭṭān, who outlined a similar schema involving Companions and Followers.[48]

Still, despite locating the origins of Hadith criticism with the Companions, Siddiqi and Murad seem to have conceded that its systematisation into a formal discipline only occurred as late as Šuʿbah and his students:

The Companions’ practice of ḥadīth criticism was emulated by people such as Shuʿba ibn al-Ḥajjāj, Yaḥyā ibn Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān, ʿAlī ibn al-Madīnī and Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, who laid the groundwork for the science of the principles of ḥadīth criticism. Thus developed two major branches of literature: ʿilm riwāyat al-ḥadīth, also called muṣṭalaḥ al-ḥadīth (the science of ḥadīth narration, or technical ḥadīth vocabulary), and ʿilm al-jarḥ wa’l-taʿdīl (the science of criticism of the reporters).[49]

In short, according to Siddiqi and Murad, Hadith criticism—including tradent criticism—originated with the Companions and passed from them to the Followers and thence to the great traditionists of the 8th Century CE, before becoming systematised or formalised via the likes of Šuʿbah and his students.

Gautier Juynboll (1997)

In his 1997 encyclopaedia entry ‘S̲h̲uʿba b. al-Ḥad̲j̲d̲j̲ād̲j̲’, Gautier Juynboll reiterated his thesis that Šuʿbah was the founder of tradent criticism:

Alongside his reputation as a great ḥadīt̲h̲ transmitter, S̲h̲uʿba’s fame lies also in his expertise in d̲j̲arḥ wa-taʿdīl, the science of disparaging and declaring trustworthy ḥadīt̲h̲ transmitters, a science of which he is generally considered to have been the first exponent and which earned him the honorific ḳabbān al-muḥaddit̲h̲īn, the steelyard of transmitters. There are numerous anecdotes in the sources describing him as particularly wary of kad̲h̲ib, mendacity, sc. in ḥadīt̲h̲. Thus he reproached the ḳuṣṣāṣ, the story-tellers [see ḳāṣṣ], for having “added” to traditions. He is even recorded as having expressed the desire to drag a notorious ḥadīt̲h̲ forger, one Abān b. Abī ʿAyyās̲h̲ (d. 138/755), to the court of the local ḳāḍī.[50]

Juynboll did not add any new evidence for the relevant thesis in this instance, relying instead upon his prior research in Muslim tradition.

Herbert Berg (2000)

In his 2000 monograph The Development of Exegesis in Early Islam, Herbert Berg recapitulated Juynboll’s revisionist chronology of the Hadith development, in the following:

It is reported that Shaʿbī (d. 103-10/721-8) was the first person to question someone about an authority and that Shuʿba ibn al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/777) was the first to examine every isnād. And so, systematic rijāl criticism began about 130/747. Hence, isnāds did not appear as early as many Muslim scholars believe. For Juynboll, the fitna to which Ibn Sīrīn alluded was the war between the Umayyads and Zubayrids. This scenario, which places the origin of the isnād around the year 70/690 (as opposed to 35/656), makes the awāʾil account of the first isnād critics much more plausible.[51]

Berg’s statement about the plausibility of Juynboll’s cited evidence, along with certain subsequent positive statements about Juynboll’s “considerable advances”,[52] give the impression that Berg generally affirms his chronology, or in other words: on the basis of Juynboll’s research, Berg seems to accept that al-Šaʿbī engaged in the first instance of isnad criticism and that Šuʿbah was the first systematic isnad or tradent critic.

Houari Touati (2000)

In his 2000 monograph Islam et Voyages au Moyen Âge, Houari Touati touched upon early Hadith transmission and the custom of journeying in search of Hadith, along with aspects of the history of Hadith criticism. Thus, after summarising some material on the concept of reliable and unreliable tradents, Touati commented:

From this attempt to discriminate between good and bad transmitters there arose an entire scientific discipline designated by the periphrasis “knowledge of men.” The medieval sources depict Shuʿba ibn al-Ḥajjāj (d. 160/776) as one of the first critics in Iraq who attempted an “inquiry about men.” They show him traveling about, both to gather traditions and to assure himself of the reliability of their guarantors.[53]

Touati—citing Heinrich Schützinger, whose work I cannot presently access, but who was presumably citing in turn the standard sources on this issue—ostensibly or noncommittally accepts that Šuʿbah was one of the first tradent critics in Iraq, although it is unclear whether he thought that this Iraqian development was unprecedented or isolated. Absent more details, it is difficult to classify Touati’s view or relate it to the others under consideration.

Eerik Dickinson (2001)

A breakthrough in understanding regarding Hadith criticism was achieved by Eerik Dickinson, whose 2001 monograph The Development of Early Sunnite Ḥadīth Criticism has revolutionised secular Hadith Studies. According to Dickinson:

The main tool the critic had for determining the authenticity of a given ḥadīth was the collation of all of the versions of the ḥadīth at his disposal. This gave him a birdseye view of the history of the transmission of the text and enabled him to trace the passage of the ḥadīth through time, from the teachers of one generation to the students of the next.[54]

Moreover:

…when a transmitter’s ḥadīth closely matched those of his peers, he was considered reliable and when he transmitted ḥadīth unknown to his fellow students, it was feared that he was a forger. However, if a student transmitted a ḥadīth unparalleled in the transmissions of his peers, it might be accepted on the basis of his previously established good reputation. Such cases were evaluated individually.[55]

In short, the collation and comparison of texts and transmissions was the chief tool or procedure of the Hadith critics, by means of which the reliability of a tradent was established and, thereby, the soundness of their hadiths. Although this basic insight was already pre-empted by Azami, it was outlined by Dickinson in greater detail, with better evidence, and with greater nuance.[56] Whether for this reason or some other,[57] it was Dickinson, rather than Azami, whose work transformed the understanding of the actual method of proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism in the secular academy.

Although mainly focusing on the methodology and maturation of Hadith criticism in the Taqdimah of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʾabī Ḥātim al-Rāzī (d. 327/938), Dickinson also touched upon the question of its origins, and in this respect, he adopted an even more revisionist stance than Fück, Crone, and Juynboll. According to Dickinson, 9th- and 10th-Century Hadith partisans and Hadith critics like Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim created a false Hijazian genealogy for their methodology (vis-à-vis the hated rationalists of Kufah), falsely retrojecting it back to notable traditionists in the 8th Century CE:

In the Taqdima Ibn Abī Ḥātim constructs a genealogy which connects ḥadīth criticism to prestigious scholars from earlier generations. Although the Taqdima addresses the objections of the ahl al-raʾy and ahl al-kalām, its author was preaching to the choir. Associating ḥadīth criticism with the likes of Mālik and Sufyān b. ʿUyayna, as is done in the Taqdima, would mean little outside of Ḥijāzian circles. Ibn Abī Ḥātim targets those Ḥijāzian scholars whose faith may have been undermined by the Kūfans. He does not offer a point by point refutation of the Kūfans, but a blanket affirmation of the legitimacy and validity of ḥadīth criticism. His reassuring message is that ḥadīth criticism is firmly based in the practice of their famous Ḥijāzian forebears.[58]

Dickinson continues:

The Taqdima purports to be the record of the transmission of the method of ḥadīth criticism from its first practitioners to Abū Ḥātim and Abū Zurʿa, Ibn Abī Ḥātim’s principal mentors and his main sources for the technical judgements in Jarḥ. In fact, what Ibn Abī Ḥātim does is anachronistically project the critical technique of his contemporaries back three generations to scholars unacquainted with it, in order to provide prestigious precedents for its usage. Ibn Abī Ḥātim was not the only scholar to attempt to justify ḥadīth criticism on basis of its usage by earlier scholars, but the Taqdima is the most ambitiously conceived and elaborately executed work of this kind.[59]

Dickinson continues further:

The success of Ibn Abī Ḥātim’s genealogy hinges on his making a plausible case that the eighteen scholars who form his four ṭabaqas were critics. The amount of space devoted to each critic varies greatly, with more generally allotted to the early ones. This correlates with the difficulty involved in making the case for the earlier scholars’ status as critics. Everyone knew that ʿAlī b. al-Madīnī was a critic of ḥadīth, so Ibn Abī Ḥātim gives him only a page and a half. The notion that Mālik was a critic must have astounded many people—since he certainly was not—and we find that Ibn Abī Ḥātim has to devote thirty-five pages to marshalling evidence that he was one. The exceptions to this general pattern are the later critics, Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal, Abū Zurʿa and Abū Ḥātim. By giving them more extensive entries, Ibn Abī Ḥātim sought to fix them firmly in the genealogy he had established as the three most prominent exponents of ḥadīth criticism in the third/ninth century.[60]

In order to achieve his goal of associating his method with earlier figures like al-ʾAwzāʿī, Mālik, and Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim cited various reports that he interpreted or framed as instances of Hadith criticism.[61] However, such reports are usually equivocal or even straightforwardly irrelevant to Hadith criticism. This is true even of the putative technical judgements ascribed to these earlier figures, which Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim also cites more of (again, compensating for the overall implausibility of his thesis):

The number of critical pronouncements varies, with more being cited for the earlier critics and fewer for the later. For the scholars of the first generation, Ibn Abī Ḥātim seems to be supplying all of the technical pronouncements he knows. He drops this approach in his treatment of the later generations, stating (p. 219) that he cites only enough to make his point.

In addition to the difference in the quantity of the technical pronouncements between the first generation and the later ones, there is also a palpable variation in quality. Many of those Ibn Abī Ḥātim quotes for the scholars of the first generation are rather scrappy, often deviating from the conventional forms of such pronouncements and occasionally having no obvious connection with ḥadīth criticism.[62]

Moreover, many of the statements regarding the reliability or unreliability of specific tradents that are attributed to the 8th-Century figures—including Šuʿbah—flatly contradict those of the Hadith critics of the 9th and 10th Centuries CE, forcing Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim and others to try and explain away the former or reconcile the two.[63] By contrast, the simple solution to this recurring conflict is to reject Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim’s thesis, according to Dickinson: “The modern student can cut through this Gordian knot by declaring these early scholars not to be critics at all.”[64] Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim and his fellows were successful in their efforts,[65] however, and it is now taken for granted—not just by traditional Sunnī scholars, but also by many secular scholars—that 8th-Century figures like Mālik were Hadith critics as well.

That said, Dickinson stressed that Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim did not fabricate or interpolate the evidence that he adduced to argue that Šuʿbah et al. were Hadith critics—on the contrary, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim “appears to have been extremely conscientious in the citation of transmitted material,” only going so far as to abridge some reports for the sake of concision and clarity.[66] Instead, Dickinson argued that Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim had to resort to decontextualisation and misinterpretation in order to retroject Hadith criticism unto Šuʿbah et al., staying within the parameters of the existing reports at his disposal:

Needless to say, his interpretations of the reports are not always convincing. More than anything else, perhaps, his failures in this regard speak to his essential honesty in the reproduction of the material he cites, for, if he had desired, he certainly could have altered many of the reports to fit his requirements better.[67]

Dickinson thus seems to have espoused a view of Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim and his like similar to that of Robson’s: such Hadith critics evidently held to a literalist or historicist view of Hadith as (more or less) fixed texts that ought not be altered (at least in such a way as to change their meaning).

In short, Dickinson argued: that Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim’s citation of many more reports on 8th-Century figures than 9th- and 10th-Century figures in his history of Hadith criticism was an act of compensation, given that the former were not actually Hadith critics (pp. 41-42); that Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim was scraping the bottom of the barrel in his citation of putative technical judgements from these 8th-Century figures, again because they were not actually Hadith critics (p. 80); that the reports cited by Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim in this regard were largely equivocal or irrelevant to Hadith criticism, again because these early figures were not actually Hadith critics (pp. 43-44, 57-58, 80); and that the judgements of these 8th-Century figures frequently contradicted those of the 9th- and 10th-Century Hadith critics, because the former were not actually Hadith critics and thus did not use the same methods in their assessment of tradents and hadiths (pp. 80-81, 91-92, 128-129). Thus, according to Dickinson, 8th-Century figures such as al-ʾAwzāʿī, Šuʿbah, Mālik, and Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah were not Hadith critics. Instead, on Dickinson’s view, Hadith criticism seems to have arisen around the turn of the 9th Century CE, emerging into the full light of history with the generation of Ibn Maʿīn, Ibn al-Madīnī, and Ibn Ḥanbal.[68]

Scott Lucas (2004)

Dickinson’s revisionist thesis was quickly criticised by Scott Lucas, whose 2004 monograph Constructive Critics, Ḥadīth Literature, and the Articulation of Sunnī Islam more-or-less affirmed the genealogy of Hadith criticism presented by Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim. Thus, according to Lucas:

Despite the fascinating array of material preserved in the Taqdima, ranging from nine letters sent by al-Awzāʿī to various ʿAbbāsid administrators, to 139 reports of Shuʿba’s ḥadīth-transmitter criticism, to an elegy for Ibn Maʿīn, Eerik Dickinson is correct in his observation that “nowhere does Ibn Abī Ḥātim explicitly delineate the criteria he employed in selecting the scholars for the Taqdima.” This ambiguity has led Dickinson to a rather radical, and, in my opinion, weak, argument that Ibn Abī Ḥātim cast the first generation of scholars as ḥadīth critics in order to give the discipline of ḥadīth criticism a greater veneer of authenticity and historical depth. Despite my skepticism regarding Dickinson’s hypothesis, I do agree that the question he has raised concerning the authenticity of the critical nature of the first generation of Ibn Abī Ḥātim’s ḥadīth-transmitter critics is a most valid line of inquiry and one that I will address in the appropriate place in this chapter.[69]

To begin with, Lucas cited the following statement from Ibn Ḥibbān, in his broader genealogy of Hadith criticism and his list of mid-to-late 8th-Century Hadith critics in particular:

Amongst the strictest and most persistent of them in the selection of legal precedents (min ʾašaddi-him intiqāʾ li-l-sunan wa-ʾakṯari-him muwāẓabah ʿalay-hā)—to the point that they made that [pursuit] an occupation of theirs (ḥattá jaʿalū ḏālika ṣināʿah la-hum), without contaminating it with anything else (lā yašūbūna-hā bi-šayʾ ʾâḵar)—were three individuals: Mālik, al-Ṯawrī, and Šuʿbah.[70]

Thereafter, in an attached footnote, Lucas added:

Note that this opinion contradicts Dickinson’s just-cited accusation that Mālik, al-Thawrī, and Shuʿba were “imagined” critics in the mind of Ibn Abī Ḥātim and is a useful piece of evidence in support of the traditional narrative of the origins of Sunnī ḥadīth criticism.[71]

Thus, according to Lucas, the citation of a figure in a list of Hadith critics by a later Hadith critic is strong evidence that the figure in question was indeed a Hadith critic.

Subsequently, Lucas systematically surveyed all of the putative members of the first generations of Hadith critics cited in Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim’s Taqdimah, summarising the relevant evidence for each in succession in an effort to determine whether they were in fact Hadith critics.

al-ʾAwzāʿī

Lucas seems to concede to Dickinson that al-ʾAwzāʿī was not a Hadith critic: “The evidence for al-Awzāʿī’s role in ḥadīth criticism is particularly thin.”[72] He is almost never described or presented as a Hadith critic in any of the reports about him, and almost no judgements are ascribed to him.[73]

Šuʿbah

Lucas is emphatic that Šuʿbah was indeed a Hadith critic, contra Dickinson: “In stark contrast to al-Awzāʿī, the evidence in support of Shuʿba’s role in both ḥadīth criticism and ḥadīth-transmitter criticism is overwhelming.”[74] To begin with, Lucas notes that there are numerous judgements attributed to Šuʿbah, along with numerous reports of his general rigour, scrutiny, inquiry, etc., recorded by Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim and others.[75] Thereafter, Lucas notes that Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim received most of his reports of Šuʿbah’s judgements from ʾAbū Ḥātim (i.e., his father), Muḥammad b. Yaḥyá, and Ṣāliḥ b. ʾAḥmad, before explaining:

The purpose of this miniature exercise in source-criticism is to support the assertion that Ibn Abī Ḥātim did not merely forge the critical opinions of Shuʿba preserved in the Taqdima in order to invent a ḥadīth critic named Shuʿba, as suggested by Dickinson.[76]

If Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim had simply fabricated such reports, Lucas argues, he would have ascribed them to or via more prestigious sources.[77] Furthermore:

When we examine the short opinions of Shuʿba that have been preserved we notice both an absence of contradictory reports with regard to an individual scholar and a consistency within his language in general.[78]

Lucas concedes that the judgements attributed to Šuʿbah rarely use the standard technical language of the later Hadith critics (such as ṯiqah and ḍaʿīf),[79] but nevertheless concludes:

The evidence in support of the identification of Shuʿba b. al-Ḥajjāj as a ḥadīth critic is quite strong. The sources unanimously depict him as a master critic of ḥadīth and a modest body of his ḥadīth-transmitter opinions has survived.[80]

In short, according to Lucas, Šuʿbah was a proper Hadith critic: he was identified as such by later sources (Ibn al-Madīnī, Muslim, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim, Ibn Ḥibbān, and al-Ḏahabī), and although he did not usually employ technical Hadith-critical terminology, he nevertheless reportedly engaged in tradent criticism.

Sufyān al-Ṯawrī

Lucas seems equivocal on Sufyān al-Ṯawrī: “While there can be little doubt that Sufyān al-Thawrī was a remarkable ḥadīth scholar, his status as a ḥadīth critic requires a careful examination of the sources.”[81] There are barely any citations of his judgements in the earliest critical literature (such as the work of al-Buḵārī),[82] and those that are cited tend to be non-technical: “These reports indicate, at best, an informal method of ḥadīth-transmitter criticism”.[83] The later Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim does cite many reports from or about Sufyān, but these seem different from those of the Hadith critics: “All of the positive opinions are devoid of technical terms, and the negative ones are almost exclusively with respect to a faulty line of transmission and not a transmitter.”[84] Lucas summarised all of this as follows:

There are three important findings that can be gleaned from Sufyān al-Thawrī’s critical reports in the Taqdima. First, al-Thawrī’s criticism is confined almost exclusively to defective isnāds instead of defective transmitters. In this sense he could perhaps be considered more of a ḥadīth editor than a critic. Secondly, while al-Thawrī is conservative with negative criticisms, he is lavish in his praise and willing, like Shuʿba, to defend a controversial scholar such as Jābir al-Juʿfī. The third, and perhaps most significant finding is that the only technical terms of ḥadīth criticism that appear are in the mouths of his students. These findings are consistent not only with the analysis of the critical opinions of Shuʿba, but support the argument of Ibn Ḥibbān in Kitāb al-majrūḥīn that the second “craft” of ḥadīth criticism, namely ḥadīth-transmitter criticism (al-jarḥ wa l-taʿdīl) only began with the pupils of Sufyān al-Thawrī and his generation.[85]

Thus, although he scrutinised or criticised some hadiths and tradents, Sufyān al-Ṯawrī does not seem to have been a Hadith critic per se, according to Lucas.

Mālik

According to Lucas, Mālik is credited with “the employment of several technical terms that became normative for his discipline”,[86] above all, the term ṯiqah. Thus, Ibn ʿAdī cited an instance of Mālik’s use of the term ṯiqah maʾmūn, whilst Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim cited ten instances of Mālik’s use of the term ṯiqah (seven times in the form laysa bi-ṯiqah), and one instance each of the terms laysa bi-ḏāka, ṣāliḥ, and kaḏḏāb, along with an instance of the term dajjāl min dajājilah, “the unique term for which he is most particularly famous”.[87] Alongside this evidence, Lucas cites a report from Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah claiming that Mālik was the strictest of all in the scrutiny of tradents,[88] along with another report that Mālik advised his students to avoid four types of tradents: the senile, the sectarian proselytizer, the liar, and the pious ignoramus.[89] Lucas thus concludes:

…the evidence we have scrutinized in these sources not only testifies to Mālik’s status as a bona fide ḥadīth critic, but indicates that Mālik was one of the first scholars to engage in ḥadīth-transmitter criticism and employ its technical vocabulary.[90]

In short, according to Lucas, Mālik was a proper Hadith critic: he was identified as such by later sources (Ibn al-Madīnī, Muslim, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim, and Ibn Ḥibbān); he reportedly engaged in tradent criticism; and he reportedly employed some technical Hadith-critical terminology.

Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah

Based on his hypothesis that “ḥadīth-transmitter criticism emerged from general ḥadīth criticism during the second half of the second/eighth century”, Lucas expects “to find technical terms associated with” Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah, who also appears in Muslim’s list of preceding Hadith critics.[91] This is seemingly confirmed by the fact that al-Buḵārī preserved many judgements from Ibn ʿUyaynah, including three descriptions of his having declared a tradent to be weak (yuḍaʿʿifu-hu).[92] Likewise, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim cites numerous judgements from Ibn ʿUyaynah, including: eight instances of ṯiqah; one instance of ṣadūq; two instances of ṣidq; an instance of ʾaṣdaq and ʾawṯaq together; a report of his having yuḍaʿʿifu-hu; and a report that he taraka someone’s transmissions.[93] From all of this, Lucas concludes:

Ibn ʿUyayna qualifies as a genuine ḥadīth-transmitter critic on the basis of the evidence I have subjected to analysis. He followed the lead of Shuʿba, in that he was willing to criticize transmitters instead of individual ḥadīth, and to employ technical terms that came into circulation on a rather limited scale in the circles of Mālik.[94]

In short, according to Lucas, Ibn ʿUyaynah was a proper Hadith critic: he was identified as such by later sources (Muslim, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim, and Ibn Ḥibbān); he reportedly engaged in tradent criticism; and he reportedly employed some technical Hadith-critical terminology.

Ibn al-Mubārak

Although initially skeptical based on Ibn al-Mubārak’s military preoccupations, Lucas argues that he too was a Hadith critic: “The evidence in favor of the identification of Ibn al-Mubārak as a ḥadīth critic is similar to that which I presented with respect to Ibn ʿUyayna.”[95] Thus, al-Buḵārī cites reports that he taraka the Hadith of seven men, and a single report of his having yuḍaʿʿifu-hu.[96] Likewise, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim records two reports of his using the term ṯiqah; that Ibn al-Mubārak’s students observed that he rejected the Hadith of four men; and a report that Ibn al-Mubārak preferred one of al-Zuhrī’s students over another, because the student copied directly from al-Zuhrī’s notebooks.[97] As such, Lucas concludes:

Despite some initial skepticism as to whether Ibn al-Mubārak can accurately be described as a ḥadīth critic, our analysis of his opinions preserved by al-Bukhārī and Ibn Abī Ḥātim makes his case as strong, if not stronger, than for those of Ibn ʿUyayna and Mālik.[98]

In short, according to Lucas, Ibn al-Mubārak was a proper Hadith critic: he was identified as such by later sources (Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim and Ibn Ḥibbān); he reportedly engaged in tradent criticism; and he reportedly employed some technical Hadith-critical terminology.

Wakīʿ

Lucas also accepted that the Kufan traditionist Wakīʿ b. al-Jarrāḥ (d. 196-197/812) was a proper Hadith critic: “The evidence in support of Wakīʿ’s critical capacity is congruous to that which I just extracted for Ibn al-Mubārak.”[99] Thus, Ibn Saʿd recorded an instance of his describing a tradent as ʾaṣaḥḥ and ʾawṯaq; al-Buḵārī mentioned two tradents whose Hadith Wakīʿ rejected; and Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim recorded sixteen instances of his using the term ṯiqah, two instances of ṯabt, and a few negative judgements, including an instance of his having yuḍaʿʿifu.[100] Lucas also comments on Wakīʿ’s teaching procedures, in relation to his being a Hadith critic:

The fact that several of these examples in which Wakīʿ evaluates a transmitter occur in the course of his recitation of the isnād of a ḥadīth is consistent with our finding with regard to the practice of Ibn ʿUyayna and suggests that this was the method by which the first ḥadīth-transmitter critics informed their students of the reliability of their predecessors.[101]

Thereafter, Lucas concluded:

The inescapable conclusion from the evidence gleaned from these three early sources is that Wakīʿ was a ḥadīth-transmitter critic in the same style as his senior contemporaries Ibn ʿUyayna and Ibn al-Mubārak, even though he seems to have been relatively reluctant to reject and swift to praise his erudite predecessors found in the isnāds of the ḥadīth which he transmitted.[102]

In short, according to Lucas, Wakīʿ was a proper Hadith critic: he was identified as such by later sources (Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim and Ibn Ḥibbān); he reportedly engaged in tradent criticism; and he reportedly employed some technical Hadith-critical terminology.

Yaḥyá al-Qaṭṭān & Ibn Mahdī

Lucas also accepted that Yaḥyá b. Saʿīd al-Qaṭṭān and ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdī were proper Hadith critics: they were identified as such by later sources (Ibn al-Madīnī, Muslim, Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim, Ibn Ḥibbān, and al-Ḏahabī); they feature as key transmitters of the judgements of Šuʿbah and al-Ṯawrī; and Ibn Mahdī in particular was attributed various notable statements concerning the profession.[103] Yaḥyá is cited far more than Ibn Mahdī for judgements by al-Buḵārī,[104] but both employed the familiar terminology of Hadith criticism: “The whole gamut of technical terms that we have been watching carefully is present in the succinct remarks of both Ibn Mahdī and Yaḥyā l-Qaṭṭān found in al-Bukhārī’s small book, and it is clear that these two men played a major role as the bridge between their teachers who were hesitant to criticize individual transmitters, at least on a large scale, and their relentlessly inquisitive pupils”—namely, the leading Hadith critics Yaḥyá b. Maʿīn and ʾAḥmad b. Ḥanbal.[105]

al-Šāfiʿī

Lucas agrees with Schacht—along with Wael Hallaq and Christopher Melchert—that al-Šāfiʿī was not himself a Hadith critic: he openly cited the expertise of the Hadith critics as an outsider; he was not usually listed as a Hadith critic in later key works; and very few technical judgements are cited from him by later Hadith critics.[106] (In this respect, Schacht, Hallaq, Melchert, and Lucas all contradict Azami, who included al-Šāfiʿī in his list of Hadith critics.) In light of this, Lucas asks the following question:

From whom did al-Shāfiʿī obtain this knowledge of ḥadīth criticism? Schacht does not offer any suggestions in these chapters, but, given the preponderance of ḥadīth in the Risāla from his teachers Mālik and Ibn ʿUyayna, whose credentials as critics are highly plausible, it would appear that these two Ḥijāzī authorities introduced al-Shāfiʿī to this new discipline.[107]

In short, al-Šāfiʿī was a supporter of Hadith criticism, but not himself a Hadith critic.

Conclusion

Following his survey of the first two generations of Hadith critics (from the middle of the 8th to the beginning of the 9th Centuries CE), Lucas summarised his motivation as follows:

I argued on the basis of the extant textual evidence that the major Sunnī ḥadcritics of the second and third periods of our historical development scheme were unequivocal critics, but I felt obliged to affirm the accuracy of this appellation for the nine primary critics of the first period. This defense was necessary due to a recent Western scholar’s skepticism of the critical credentials of contemporaries of Shuʿba and Sufyān al-Thawrī…[108]

On the basis of the lists of the first Hadith critics recorded by various later sources, and the judgements recorded above all by al-Buḵārī and Ibn ʾabī Ḥātim, Lucas affirmed—against the findings of Dickinson—that Šuʿbah, Mālik, and Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah were indeed Hadith critics. However, Lucas conceded that al-ʾAwzāʿī was not a Hadith critic (and possibly also Sufyān al-Ṯawrī?), and that Šuʿbah and the other earliest Hadith critics did not usually—or in some cases at all—employ the technical vocabulary of the later Hadith critics:

The three senior primary critics, al-Awzāʿī, Shuʿba, and Sufyān al-Thawrī do not appear to have employed any technical terms in the sources that I surveyed, whereas Mālik and Ibn ʿUyayna did so on a limited scale. Since the careers of al-Awzāʿī, Shuʿba, and Sufyān al-Thawrī overlap those of Mālik and Ibn ʿUyayna, it is quite conceivable that they too employed some of these technical terms as early as the first half of the second/eighth century. If Dickinson’s argument that Ibn Abī Ḥātim attempted dishonestly to cast Shuʿba and his contemporaries as critics is tenable, it is remarkable that Ibn Abī Ḥātim did not include any examples from his vast repertoire of reports in which these men use the term thiqa and yet did choose to include multiple thiqa reports on the authority of a scholar like Wakīʿ. The only scholar of the nine primary critics whose capacity as a critic is not supported strongly by the limited selection of early texts I have studied is that of the eldest one, al-Awzāʿī; as he is neither included in the list of the five Imāms of Muslim nor among Ibn Ḥibbān’s three “founders of the craft of ḥadīth criticism,” I would like to suggest tentatively that his juridical acumen and intuition of the sunna caused later Eastern scholars to bestow an “honorary doctorate” of ḥadīth critic upon him despite the absence of clear evidence in support of his proficiency in this discipline.[109]

In short, according to Lucas: Hadith criticism emerged in the middle of the 8th Century CE, with Šuʿbah (who engaged in tradent criticism) and others; the technical term ṯiqah arose in the next generation, with Mālik and Sufyān b. ʿUyaynah; the t–r–k root became a source of technical terms amongst their students; and finally, the technical term ḍaʿīf only seems to have arisen amongst Yaḥyá al-Qaṭṭān, Ibn Mahdī, and their contemporaries.[110]

Christopher Melchert (2006)

Christopher Melchert in turn offered a short but sharp rebuttal to Lucas in a 2006 review of the latter’s monograph, charging him with a failure to engage with Dickinson’s actual arguments:

Eerik Dickinson in The Development of Early Sunnite Ḥadīth Criticism (Leiden, 2001), dismissed Mālik and other figures of the 2nd/8th century as “not ḥadīth critics.” Lucas is so angry with Dickinson that he completely overlooks Dickinson’s important description of classical ḥadīth criticism (which is what Dickinson did not think Mālik practiced). Lucas equates isnād criticism with ʿilm al-rijāl, refers to the actual sifting of reliable from unreliable as mysterious, and implicitly identifies ḥadīth criticism with the production of characterizations of men—thiqa, ṣadūq, and so on. This is a conceptual regression from Dickinson’s exposition of isnād comparison, which he based on actual works of ḥadīth criticism.[111]

In his monograph Ahmad ibn Hanbal, published in the same year, Melchert went on to elaborate some of the features of proto-Sunnī Hadith criticism, building upon the insights of Dickinson. To begin with, Melchert concurred that Mālik was not a Hadith critic (nor even a member of the People of Hadith), and that his method of evaluating Hadith reflected the rudimentary approach of the regional legal traditions of early Islam:

Other Muslims cited hadith when arguing with those who disagreed with them on points of law but for the most part expounded the law on the bases of common sense and local tradition. Their fashion of sorting contradictory hadith was crude. Some, like Malik and other defenders of the Medinan tradition, simply cited whatever supported their own positions and ignored whatever did not. Others, such as Shaybani, Abu Hanifah’s follower, would sometimes prefer whatever claimed to be older, such as hadith from Companions as opposed to hadith from Followers.[112]

By contrast, Melchert accepted that Yaḥyá al-Qaṭṭān and Ibn Mahdī—not to mention Ibn Maʿīn and Ibn Ḥanbal—were Hadith critics,[113] and that their “chief technique” was—as Dickinson argued—the collation and comparison of transmissions, in order to ascertain corroboration and, by extension, reliability.[114] However, Melchert also noted that the Hadith critics, as members of the early People of Sunnah, sometimes engaged in certain forms of sectarian matn criticism as well:

Admittedly, unorthodox hadith were dismissed out of hand, without the usual tests. Could the Prophet really have said, “If you see Mu‘awiyah on this pulpit, kill him” (Sunnah, 134 151)? Only a Shi‘i might think so: to a Sunni like Ahmad, it was an article of faith that the Prophet’s Companions were above criticism and no isnad could make such a matn credible.[115]

Moreover, like Goldziher, Abbott, and Juynboll before him, Melchert argued that the process of examining transmissions and judging tradents and hadiths was actually highly subjective:

The ‘Ilal and similar collections of his hadith criticism suggest Ahmad used a case-by-case, seat-of-the-pants approach to determining what was sound and what was not. The large part played by intuition was sometimes acknowledged by the medieval tradition itself. The Syrian jurisprudent, al-Awza‘i (died 157/774?), said:

We used to hear hadith reports and offer them for inspection by our colleagues as one offers counterfeit dirhams for inspection. What they recognised, we took, what they rejected, we left.

(Muhaddith, 318)

When someone challenged ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Mahdi, one of Ahmad’s leading Basran shaykhs, he retorted, “When you go to an assayer with a dinar and he tells you it is counterfeit, can you say to him ‘Why do you say so?’” (Muhaddith, 312). He preferred to rely on the feel he had developed over the years. Of course, one critic’s feel was bound to be different from another’s, hence the constant disagreement in collections of hadith criticism.[116]

In short, whilst Melchert agreed with Dickinson that the Hadith critics primarily appealed to corroboration, he argued that this involved a good deal of subjectivity or even mere intuition. Melchert also argued that the critics sometimes avoided this procedure altogether when it came to unorthodox or sectarian hadiths, which they rejected simply on the basis of their content.

Benjamin Jokisch (2007)

In his 2007 monograph Islamic Imperial Law, Benjamin Jokisch accepted and reiterated the hypothesis that Šuʿbah was the founder of Hadith criticism or tradent criticism:

In other fields (liturgy, exegesis, etc.), criteria such as context, cluster of related traditions or compatibility with other traditions will have played a role. All of these criteria formed part of Islamic ḥadīth criticism, but the reputation of the informants was a particularly important one. This is supported by the centrality of the science of jarḥ wa-taʿdīl, which was reportedly introduced by the outstanding traditionist and ascetist Shuʿba b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 776), a pupil of the Qadarī Ḥasan al-Baṣrī. He was the first to lay down which of the early Muslim traditionists could be regarded as trustworthy.[117]

For all of this, Jokisch relied upon an article written by Juynboll.

It should also be noted that Jokisch’s assertion (based on Robson) that “the reputation of the informants” was “particularly important” in Hadith criticism is out of step with the research of Dickinson and Melchert.

Jonathan Brown (2009)

In his 2009 monograph Hadith, Jonathan Brown identified some kind of proto-criticism of Hadith with the Companions, who reportedly questioned, contested, and demanded independent witnesses for some claims about the Prophet:

During the lifetime of leading Companions like ‘Umar b. al-Khattāb, ‘Abdallāh b. Mas‘ūd, or Anas b. Mālik, many of whom had been with the Prophet since his early days in Mecca, it was difficult to attribute something untrue to the Prophet without a senior Companion noticing. In fact, there are many reports documenting the Companions’ vigilance against misrepresentations of the Prophet’s legacy. ‘Alī is quoted as requiring an oath from any Companion who told him a hadith from the Prophet that he himself had not heard. When the Companion Abū Mūsā al-Ash‘arī told ‘Umar that the Prophet had said that if you knocked on someone’s door three times and they did not answer you should depart, ‘Umar demanded that he find another Companion to corroborate the report.[118]

However, Brown seems to distinguish between this early activity and Hadith criticism proper (i.e., involving the systematic collation of transmissions and criticism of tradents thereby), which he associated with the generations of Šuʿbah and Mālik:

The processes of this three-tiered critical method did not emerge fully until the mid eighth century with critics like Mālik b. Anas and Shu‘ba b. al-Hajjāj. Certainly, Successors like al-Zuhrī and even Companions had examined critically material they heard attributed to the Prophet. Moreover, the critical opinions of Successors would inform later hadith critics. A formalized system of requiring isnāds and investigating them according to agreed conventions and through a set of technical terms, however, did not appear until the time of Mālik.[119]

Likewise: